Reversing the dangerous erosion of U.S. democracy is urgent, but the argument that this requires abandoning efforts to uphold democratic values elsewhere has it backwards, say two leading observers.

Commitments to democratic values at home and overseas are mutually reinforcing. Ignoring—or worse, abetting—human rights violations abroad corrodes the rule of law and democracy here, argue Stephen McInerney and Amy Hawthorne, executive director and deputy director for research, respectively, at the Project on Middle East Democracy (POMED).

POMED

American officials accustomed to turning a blind eye to abuses elsewhere are more likely to do the same at home. If we believe in democracy for ourselves, we must defend democratic values everywhere, even as we work to address our own deep problems. As the world’s most powerful country, whose actions affect the state of democracy elsewhere—and which is itself affected by the global rise of authoritarianism—the United States must look inward and outward at the same time.

“President-elect Joe Biden seems to understand this,” they add. “He has promised to restore the rule of law and repair democracy here while also putting ‘democracy and human rights at the center of America’s foreign policy.’ At the core of his administration’s efforts should be Tunisia, the Arab world’s lone democracy.”

To mark the 10th anniversary of the Jasmine Revolution, Carnegie’s Sarah Yerkes and Nesrine Mbarek (above) asked Tunisians what they thought of the perilous journey their country has made toward democracy—and what their hopes are for the future.

Free elections have been held, but politics are often tumultuous, France24 adds. Some 13 different governments have run the country in the decade since the revolution, amid an ongoing economic crisis.

Free elections have been held, but politics are often tumultuous, France24 adds. Some 13 different governments have run the country in the decade since the revolution, amid an ongoing economic crisis.

Tunisia may be the one democracy to emerge from the Arab Spring, but major challenges remain — including a sluggish economy, police brutality, and disillusionment with the system, adds Sharan Grewal, an assistant professor of government at William & Mary and a nonresident senior fellow at POMED, a partner of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). Paradoxically, each of these challenges may have been exacerbated by the very factors that helped Tunisia’s democracy survive in the early years of its transition. Its drive for consensus, weak security sector and powerful civil society help to explain both why Tunisia has succeeded and why it has not yet consolidated, he writes for the Post.

History has proven that democracy is a process, not a destination. Despite its democratic progress, Tunisia remains plagued by many of the same grievances that provoked the country’s revolution in 2011, writes Sacha Gilles,

History has proven that democracy is a process, not a destination. Despite its democratic progress, Tunisia remains plagued by many of the same grievances that provoked the country’s revolution in 2011, writes Sacha Gilles,

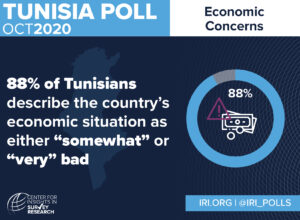

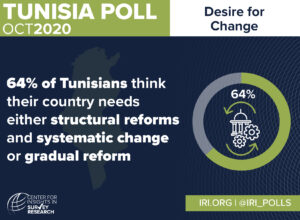

As often occurs in the lead up to this anniversary, Tunisia is witnessing a spike in protests and sit-ins across the country that underscore the unfulfilled promises of the revolution and citizens’ dissatisfaction with the government. Recent IRI polling (above) has in fact found that 87 percent of Tunisians believe their country is heading in the wrong direction, and only 23 percent consider Tunisia a full or nearly full democracy. To reinvigorate citizens’ faith in the democratization process, stakeholders must fight for meaningful reforms that address the injustices that sparked the revolution.

“A decade after the revolution, Tunisia has made progress in its democratization, but challenges with the economy and corruption remain,” said IRI Regional Director for the Middle East and North Africa Patricia Karam. “The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated these issues, encouraging citizens to seek new reforms and leadership to address them.”

A Decade of Strengthening Democracy in Tunisia https://t.co/fTJ6RW2WPa via @IRIglobal

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) January 14, 2021