Russia‘s conduct of the war in Ukraine flouts the most basic international laws and conventions, posing a fundamental threat to the global order. As such, it offers a textbook example of the Age of Impunity, says former British Foreign Secretary David Miliband.

It’s not just war zones. Impunity is a helpful lens through which to understand the global drift to “polycrisis,” from climate change to the weakening of democracy, he writes for The New York Times. When billionaires evade taxes, oil companies misrepresent the severity of the climate crisis, elected politicians subvert the judiciary and human rights are rolled back, you see impunity in action. Impunity is the mind-set that laws and norms are for suckers.

Ukrainians’ desire for a free, democratic nation inspired them to fight and enabled them to endure casualties and destruction on a very large scale, argues Dr Rob Johnson, the Director of the Changing Character of War Research Centre at Oxford’s Pembroke College.

Ukrainians’ desire for a free, democratic nation inspired them to fight and enabled them to endure casualties and destruction on a very large scale, argues Dr Rob Johnson, the Director of the Changing Character of War Research Centre at Oxford’s Pembroke College.

Russia has often suffered defeats when its soldiers reject the conditions they are forced to endure, when the economy is placed under intolerable pressure, when the truth of the waste in lives starts to come home, and when their leaders are exposed as incompetent. Those conditions are now emerging. If the end comes for Putin, it is likely to be swift, adds Johnson, currently on secondment to the Ministry of Defence where he has been intimately involved in assessing the conflict in Ukraine.

Russia on Friday accused the United States of inciting Ukraine to escalate the war by condoning attacks on Crimea, warning that Washington was now directly involved in the conflict because “crazy people” had dreams of defeating Russia, Reuters reports:

Moscow was responding to comments by U.S. Under Secretary of State Victoria Nuland (right) who said the United States considers that Crimea, which Russia annexed from Ukraine in 2014, should be demilitarised at a minimum and that Washington supports Ukrainian attacks on military targets on the peninsula.

Moscow was responding to comments by U.S. Under Secretary of State Victoria Nuland (right) who said the United States considers that Crimea, which Russia annexed from Ukraine in 2014, should be demilitarised at a minimum and that Washington supports Ukrainian attacks on military targets on the peninsula.

“No matter what the Ukrainians decide about Crimea in terms of where they choose to fight etcetera, Ukraine is not going to be safe unless Crimea is at a minimum, at a minimum, demilitarized,” Nuland told the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

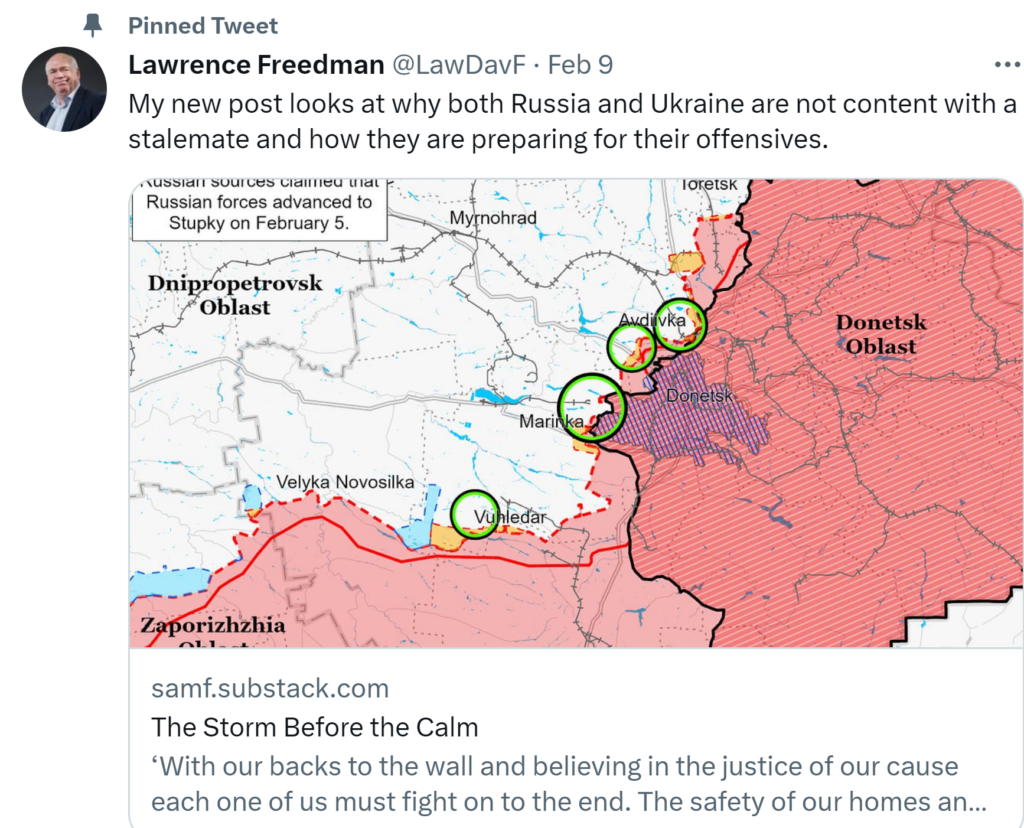

As Russia has become more frustrated in its campaign to occupy Ukraine, it has resorted to regular attacks on civil society and the economy, but the onslaught has made no dent in popular support for Ukraine’s government, strategist Lawrence Freedman writes in Kyiv and Moscow Are Fighting Two Different Wars, an article for Foreign Affairs.

The war has revealed the full extent of Putin’s personalized political system, according to Brookings analyst Fiona Hill, the author of There Is Nothing for You Here: Finding Opportunity in the Twenty-first Century, and Angela Stent, the author of Putin’s World: Russia Against the West and With the Rest. After what is now 23 years at the helm of the Russian state, there are no obvious checks on his power. Institutions beyond the Kremlin count for little.

The war has revealed the full extent of Putin’s personalized political system, according to Brookings analyst Fiona Hill, the author of There Is Nothing for You Here: Finding Opportunity in the Twenty-first Century, and Angela Stent, the author of Putin’s World: Russia Against the West and With the Rest. After what is now 23 years at the helm of the Russian state, there are no obvious checks on his power. Institutions beyond the Kremlin count for little.

Diplomats, policymakers, and analysts are stuck in a doom loop—an endless back-and-forth argument among themselves—to figure out what Putin wants and how the West can shape his behavior, they write for Foreign Affairs:

Western debates about the need to weaken Russia, the importance of overthrowing Putin to achieve peace, whether democracies should line up against autocracies, and whether other countries must choose sides have muddied what should be a clear message: Russia has violated the territorial integrity of an independent state that has been recognized by the entire international community, including Moscow, for more than 30 years. Russia has also violated the UN Charter and fundamental principles of international law. If it were to succeed in this invasion, the sovereignty and territorial integrity of other states, be they in the West or the global South, will be imperiled.

Unlike, for instance, the Thirty Years’ War, the American Civil War, or the Arab-Israeli wars, this war is not the result of social processes that involved thinkers, writers, orators and grassroots movements over many years, says Hartman Institute fellow Amotz Asa-El. The Ukraine war emerged from one man’s mind – the man who remains the only one who can end it. This autocratic context, and the bloodbath that is its result, should serve as a warning to democracy’s discontents elsewhere, he writes for the Jerusalem Post.

Unlike, for instance, the Thirty Years’ War, the American Civil War, or the Arab-Israeli wars, this war is not the result of social processes that involved thinkers, writers, orators and grassroots movements over many years, says Hartman Institute fellow Amotz Asa-El. The Ukraine war emerged from one man’s mind – the man who remains the only one who can end it. This autocratic context, and the bloodbath that is its result, should serve as a warning to democracy’s discontents elsewhere, he writes for the Jerusalem Post.

Russia is heading for defeat, and the last thing Western countries should do is offer it a lifeline by slowing aid or pushing for premature negotiations, says the Renew Democracy Initiative. As Garry Kasparov said, “The story of this war is the best demonstration of what free people are capable of.

Russia’s misjudgment of Germany, and Germany’s turnaround, has played a significant role in a war many assumed would end in a swift Ukrainian defeat, say Liana Fix and Caroline Kapp.

Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s Zeitenwende commitments have drawn criticism for hesitation, slow implementation, and deference to U.S. leadership. Nevertheless, Germany has squarely refuted Putin’s expectations. In fact, Russia’s war has triggered the greatest transformation in German foreign and security policy since the end of the Cold War, they write for the CFR.

The National Endowment for Democracy (NED) hosts a virtual discussion on “Shielding Democracy: Civil Society Adaptations to Kremlin Disinformation about Ukraine.”

The National Endowment for Democracy (NED) hosts a virtual discussion on “Shielding Democracy: Civil Society Adaptations to Kremlin Disinformation about Ukraine.”

Panelists: Peter Pomerantsev, senior fellow at Johns Hopkins University; Olha Bilousenko, head of Detector Media’s Research Center; Veronika Vichova, deputy director for analysis and head of the European Values Center for Security Policy’s Kremlin Watch Program; and Adam Fivenson, senior program officer for information space integrity at the NED International Forum for Democratic Studies. 10:30 a.m. February 22, 2023. Full details here.