China is deploying information operations through the placement of paid media articles as part of a broader campaign to burnish its image in the Taiwanese media, Reuters reports:

China is deploying information operations through the placement of paid media articles as part of a broader campaign to burnish its image in the Taiwanese media, Reuters reports:

Reuters has found evidence that mainland authorities have paid at least five Taiwan media groups for coverage in various publications and on a television channel, according to interviews with 10 reporters and newsroom managers as well as internal documents reviewed by Reuters, including contracts signed by the Taiwan Affairs Office, which is responsible for overseeing China’s policies toward Taiwan….The Taiwan Affairs Office paid 30,000 yuan ($4,300) for the two feature stories about the mainland’s efforts to attract Taiwan business people, according to a person familiar with the arrangements and internal documents from the newspaper.

“What is disappointing is that the reporters and the headline writers are using the ‘hearts and minds’/’soft power’ framing when the entire piece screams sharp power, which is influence that aims to manipulate, degrade authentic understanding, and induce self-censorship,” said Christopher Walker, Vice President for Studies and Analysis at the National Endowment for Democracy.

At least the Reuters source appears to get it.

“It felt like I was running propaganda and working for the Chinese government,” the person said.

In an exploratory blog post, Harvard Kennedy School fellow and lecturer Bruce Schneier first laid out a straw man information operations kill chain, starting with the seven commandments, or steps, laid out in a 2018 New York Times opinion video series on “Operation Infektion,” a 1980s Russian disinformation campaign.

In an exploratory blog post, Harvard Kennedy School fellow and lecturer Bruce Schneier first laid out a straw man information operations kill chain, starting with the seven commandments, or steps, laid out in a 2018 New York Times opinion video series on “Operation Infektion,” a 1980s Russian disinformation campaign.

The information landscape has changed since the ’80s, and these operations have changed as well, prompting him to change the name from “information operations” to “influence operations”, he writes for Foreign Policy, and to modify and update those steps to include:

- Step 4: Wrap narratives in kernels of truth. A core of fact makes falsehoods more believable and helps them spread. ….Countermeasures: Defenses involve exposing the untruths and distortions, but this is also complicated to put into practice. Fake news sows confusion just by being there. Psychologists have demonstrated that an inadvertent effect of debunking a piece of fake news is to amplify the message of that debunked story.

- Step 5: Conceal your hand. Make it seem as if the stories came from somewhere else. Countermeasures: Here the answer is attribution, attribution, attribution. The quicker an influence operation can be pinned on an attacker, the easier it is to defend against it. This will require efforts by both the social media platforms and the intelligence community, not just to detect influence operations and expose them but also to be able to attribute attacks.

Step 6: Cultivate proxies who believe and amplify the narratives. Traditionally, these people have been called “useful idiots.” Encourage them to take action outside of the internet, like holding political rallies, and to adopt positions even more extreme than they would otherwise. Countermeasures: We can mitigate the influence of people who disseminate harmful information, even if they are unaware they are amplifying deliberate propaganda. … Additionally, the antidote to the ignorant people who repeat and amplify propaganda messages is other influencers who respond with the truth—in the words of one report,we must “make the truth louder.”

Step 6: Cultivate proxies who believe and amplify the narratives. Traditionally, these people have been called “useful idiots.” Encourage them to take action outside of the internet, like holding political rallies, and to adopt positions even more extreme than they would otherwise. Countermeasures: We can mitigate the influence of people who disseminate harmful information, even if they are unaware they are amplifying deliberate propaganda. … Additionally, the antidote to the ignorant people who repeat and amplify propaganda messages is other influencers who respond with the truth—in the words of one report,we must “make the truth louder.” - Step 7: Deny involvement in the propaganda campaign, even if the truth is obvious. Although since one major goal is to convince people that nothing can be trusted, rumors of involvement can be beneficial. The first was Russia’s tactic during the 2016 U.S. presidential election; it employed the second during the 2018 midterm elections. Countermeasures: When attack attribution relies on secret evidence, it is easy for the attacker to deny involvement. Public attribution of information attacks must be accompanied by convincing evidence. This will be difficult when attribution involves classified intelligence information, but there is no alternative. Trusting the government without evidence, as the NSA’s Rob Joyce recommended in a 2016 talk, is not enough. Governments will have to disclose.

- Step 8: Play the long game. Strive for long-term impact over immediate effects. Engage in multiple operations; most won’t be successful, but some will. Countermeasures: Counterattacks can disrupt the attacker’s ability to maintain influence operations, as U.S. Cyber Command did during the 2018 midterm elections. The NSA’s new policy of “persistent engagement” (see the article by, and interview with, U.S. Cyber Command Commander Paul Nakasone here) is a strategy to achieve this. So are targeted sanctions and indicting individuals involved in these operations.

Clint Watts of the Alliance for Securing Democracy is thinking along these lines as well, while the Credibility Coalition’s Misinfosec Working Group proposed a “misinformation pyramid, and the U.S. Justice Department has developed a “Malign Foreign Influence Campaign Cycle,” with associated countermeasures, adds Schneier.

Clint Watts of the Alliance for Securing Democracy is thinking along these lines as well, while the Credibility Coalition’s Misinfosec Working Group proposed a “misinformation pyramid, and the U.S. Justice Department has developed a “Malign Foreign Influence Campaign Cycle,” with associated countermeasures, adds Schneier.

The Global Disinformation Index’s latest research about the threats posed by the spread of disinformation makes for disturbing reading, adds Coda Story. The report explains how bad actors have mastered the frameworks of our online world and are intent on using digital tools as weapons of fifth generation warfare, or 5GW, a free-for-all motivated by frustration rather than ideology. Here’s what the researchers found:

- The landscape of today’s online threats is significantly more complex, which may lead to many abusive and harmful behaviors slipping through the gaps of our current moderation models.

- Disinformation agents, both domestic and foreign, have a large library of content to draw from in crafting new adversarial narratives. In practice this means less overtly fabricated pieces of content.

- Adversarial narratives like “Stop 5G” campaigns — which seek to halt the expansion of new mobile networks — are effective because they infame social tensions by exploiting and amplifying perceived grievances of individuals, groups and institutions. The end game is to foster long-term social, political and economic conflict.

- One key element of these disinformation campaigns is that they contain elements of factual information that are then seeded throughout.

- As seen in the “Stop 5G” campaign, it is only consumers travel away from the original source that the fabricated conspiracy elements start to be added on.

- Understanding and defending against adversarial narratives requires analysis of both the message’s contents and context, and how disinformation spreads through networks and across platforms.

“Disinformation agents, both domestic and foreign, have a large library of content to draw from in crafting new adversarial narratives,” said the report, titled “Adversarial Narratives: A New Model for Disinformation.” “In practice this means less overtly fabricated pieces of content” and more material that draws on bits and pieces of factual information that is overlaid with conspiracy and disinformation.

“Disinformation agents, both domestic and foreign, have a large library of content to draw from in crafting new adversarial narratives,” said the report, titled “Adversarial Narratives: A New Model for Disinformation.” “In practice this means less overtly fabricated pieces of content” and more material that draws on bits and pieces of factual information that is overlaid with conspiracy and disinformation.

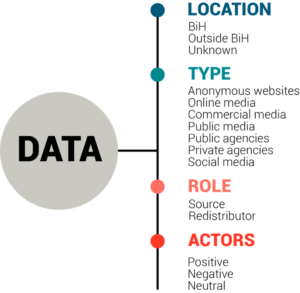

Both foreign and domestic disinformation are problems in Bosnia-Herzegovina, and awareness of the challenge there is limited, adds Darko Brkan, the founding president of Zašto ne (Why Not), a Sarajevo-based nongovernmental organization that promotes civic activism, government accountability, and the use of digital media in deepening democracy.

Research is an important step for developing future action, he writes for the NED’s international Forum’s Power 2.0 blog:

First, democratic actors need to continue fact-checking and debunking efforts in order to increase awareness, glean insights, and follow trends.

First, democratic actors need to continue fact-checking and debunking efforts in order to increase awareness, glean insights, and follow trends.- Second, since most disinformation narratives have regional reach, regional networking and cooperation is crucial.

- Third, coordinated engagement with big tech companies must include the Balkans, and these companies should play a role in minimizing the problem.

- Finally, civil society needs to engage public officials and other stakeholders in developing frameworks for fighting disinformation and improving media literacy, a key facet of public resilience.

Permeating all of this is the importance of deterrence, adds Schneier, whose latest book is Click Here to Kill Everybody: Security and Survival in a Hyper-connected World. Deterring them will require a different theory. It will require, as the political scientist Henry Farrell and I have postulated, thinking of democracy itself as an information system and understanding “Democracy’s Dilemma”: how the very tools of a free and open society can be subverted to attack that society. We need to adjust our theories of deterrence to the realities of the information age and the democratization of attackers. RTWT

The Woodrow Wilson Center hosts a forum on “Decoding the Disinformation Problem,” highlighting the history of disinformation campaigns, current patterns and challenges, including “protecting vulnerable places with the potential for violence.”

Panelists include Jessica Beyer, lecturer at the University of Washington’s Jackson School of International Studies; Ginny Badanes, director of strategic projects, cybersecurity & democracy at Microsoft; Katie Harbath, global elections director at Facebook; David Greene, civil liberties director, Electronic Frontier Foundation; Kate Bolduan, anchor at CNN; and Nina Jankowicz, fellow at the Woodrow Wilson Center.

2 p.m. August 13, 2019

Venue: Woodrow Wilson Center, One Woodrow Wilson Plaza, Ronald Reagan Building, 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW, Sixth Floor, Flom Auditorium, Washington, D.C. RSVP