With his reelection, Vladimir Putin took one step closer to becoming Russia’s leader for life. On paper, Putin’s victory gave him a new six-year term as president. But some of his most visible allies quickly signaled they saw it as a mandate for something greater than that: leader of the Russian people, rising above politics at a time when the country’s very existence is threatened by an aggressive West, the Washington Post reports:

Margarita Simonyan, the editor-in-chief of pro-Kremlin network RT, wrote that Putin had turned from president to “our leader,” or vozhd — a word with medieval roots that Soviets once used for Stalin. Vladimir Zhirinovsky, a nationalist presidential candidate who supports Putin, predicted on national television that “these elections were the last ones.” And a parade of pro-Kremlin commentators, politicians, and officials claimed that Putin’s victory represented nothing less than the unity and determination of a people under siege.

Margarita Simonyan, the editor-in-chief of pro-Kremlin network RT, wrote that Putin had turned from president to “our leader,” or vozhd — a word with medieval roots that Soviets once used for Stalin. Vladimir Zhirinovsky, a nationalist presidential candidate who supports Putin, predicted on national television that “these elections were the last ones.” And a parade of pro-Kremlin commentators, politicians, and officials claimed that Putin’s victory represented nothing less than the unity and determination of a people under siege.

“The road to presidency for life, or some other kind of lifetime post as the country’s leader, opened today,” said Konstantin Gaaze, an independent political analyst.

The poll was more of a coronation than an election or, said Arkady Ostrovsky, Russia editor for the Economist. Almost  nobody believes in the legitimacy of Russian elections, said Ostrovsky, author of The Invention of Russia.

nobody believes in the legitimacy of Russian elections, said Ostrovsky, author of The Invention of Russia.

“Choice without real competition, as we have seen here, is not real choice. The Central Election Commission’s professional and efficient administration of the technical aspects of the election deserves recognition,” said Michael Georg Link, Special Co-ordinator of the OSCE observer mission (above). “But where the legal framework restricts many fundamental freedoms and the outcome is not in doubt, elections almost lose their purpose – empowering people to choose their leaders.”

But Putin’s victory in Sunday’s presidential election has left deep divisions in an opposition movement that had been buoyed in recent months by countrywide protests, but that failed to translate its momentum into a broad political movement, the Wall Street Journal reports:

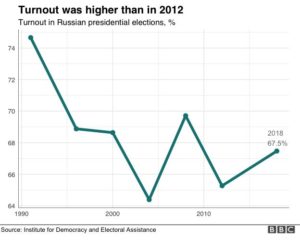

Anticorruption activist Alexei Navalny had brought tens of thousands of protesters onto the streets across Russia ahead of Sunday’s election—a vote that he was barred from participating in. But Mr. Navalny’s call for a boycott of the election appears to have had little effect, as Sunday’s turnout surpassed that of the last election in 2012.

At the same time, friction emerged Monday among opposition figures—some of whom accused the Kremlin of improprieties during Sundays’ election — as to the best way to counter Mr. Putin’s influence. ….Election watchdog Golos registered thousands of voting violations, including preventing observers from monitoring the vote.

Video recordings from polling stations showed irregularities in a number of towns and cities across Russia, the BBC adds. Several showed election officials stuffing boxes with ballot papers.

Video recordings from polling stations showed irregularities in a number of towns and cities across Russia, the BBC adds. Several showed election officials stuffing boxes with ballot papers.

Despite Putin’s strong showing in the election, the FT’s Kathrin Hille writes, Russian experts “warn that the population’s patience with economic pain and international isolation will not last forever.”

PutinCon

Putin’s “phony election” was merely “a charade to distract Russia and the world while his brutal dictatorship continues into its nineteenth year,” according to dissident and former chess grand Master Garry Kasparov. “Putin’s repression, corruption, wars, assassinations, and his interference and undermining of democratic governments will continue. For now. But his rule will not last forever,” he said.

Kasparov’s Human Rights Foundation last week hosted hundreds of advocates of Russian human rights and democracy in New York City at PutinCon, a masterclass on “how the free world can support civil society and democracy inside Russia while defending itself from Putin’s aggression.”

The election raises three questions, said Miriam Lanskoy (second from right), a senior director for Russia and Eurasia at the National Endowment for Democracy: “Will Putin be restrained? Is democracy possible in Russia? What are the ways to develop civil rights movements in Russia?”

The election raises three questions, said Miriam Lanskoy (second from right), a senior director for Russia and Eurasia at the National Endowment for Democracy: “Will Putin be restrained? Is democracy possible in Russia? What are the ways to develop civil rights movements in Russia?”

Putin, a former Soviet intelligence officer, barely bothered to campaign, except to stress his constant theme that Russia was a besieged fortress and that he was the only man to keep it safe by rebuilding its arsenal and projecting power beyond its borders, especially in challenging the United States, the New York Times reports.

But according to the Kremlin-connected VTsIOM polling agency, turnout was below 65 percent, RFERL adds:

If that figure holds, it would suggests that the regime’s ability to mobilize the public is slipping. Moreover, throughout the day there were reports of people being pressured to go to the polls and videos persistently appeared on social media showing flagrant ballot-stuffing. Speaking on Aleksei Navalny’s YouTube channel. ….Russian emigre economist Sergei Aleksashenko called the March 18 vote “a standard Soviet-Russian election of the Putin era.” And Princeton University historian Stephen Kotkin called Putin’s reelection “preordained” and “a superfluous, if vivid, additional signal of Russia’s debilitating stagnation.”

The NED’s Lanskoy presented an overall optimistic forecast at Putincon, Zarina Zabrinsky writes for Medium:

There is a new way of thinking in Congress. In particular, there is a concern about the danger of the Russian kleptocracy for the US? With time, said Lanskoy, we should see more of the sanctions and more Putin cronies should be identified. Democracy can happen in Russia. Education and conceptual foundation for democratic Russia need to be developed now. A new type of leaders is emerging: we have seen some of these politicians at PutinCon. Leaders like Navalny reach millions via the social media and this is a hope for democracy.

There is a new way of thinking in Congress. In particular, there is a concern about the danger of the Russian kleptocracy for the US? With time, said Lanskoy, we should see more of the sanctions and more Putin cronies should be identified. Democracy can happen in Russia. Education and conceptual foundation for democratic Russia need to be developed now. A new type of leaders is emerging: we have seen some of these politicians at PutinCon. Leaders like Navalny reach millions via the social media and this is a hope for democracy.

Ironically, the authoritarian methods Putin has used to consolidate power over nearly two decades have made any post-Putin era more dangerous not just for allies, but for Putin himself. Having undermined the rule of law, rights, and institutions of democracy, critics say, he cannot rely on those institutions — such as the courts — to protect him if power slips from his grasp, RFERL adds.

Ironically, the authoritarian methods Putin has used to consolidate power over nearly two decades have made any post-Putin era more dangerous not just for allies, but for Putin himself. Having undermined the rule of law, rights, and institutions of democracy, critics say, he cannot rely on those institutions — such as the courts — to protect him if power slips from his grasp, RFERL adds.

Putin “needs a safety net for himself,” said Andrei Kolesnikov, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Moscow Center and chairman of its program on domestic Russian politics. What strategy Putin will choose for 2024 and beyond “depends on a million factors,” he said.

Credit: Economist

While exploitation of state resources to bolster the candidacy of an established leader is a time-tested feature of Russian politics, this year it is completely different — and exactly the same — says Maria Lipman, editor of the Moscow-based Kontrapunkt (Counterpoint), an open-access Russian-language journal of politics and society published by George Washington University.

“The notion that Putin is a leader beyond competition was created at the very beginning of his presidency,” she told VOA. “Even in 2008, it was clear that whichever candidate Putin proposed to his fellow citizens as a successor would be accepted, supported and voted for by the nation simply because Putin recommended him.”

Andrew Wood, associate fellow of the Russia and Eurasia Program at the London-based Chatham House think-tank, told CNBC that Putin was bringing “nothing new” to Russia.

“It’s interesting (Putin) is already talking about running again and again and again,” Wood said. “(But) quarter of a century in office is just too long. He’s had nothing new to offer in this election, he’s going to carry on resisting the need for economic reform in Russia because that would include proper accountability, a proper court system, a decent press, all those things that go to make up a proper state.”