Autocrats have a talent for producing impressive election results. It isn’t difficult to win when your opponents are not on the ballot, Russian democracy activist Vladimir Kara-Murza writes for the Washington Post:

Autocrats have a talent for producing impressive election results. It isn’t difficult to win when your opponents are not on the ballot, Russian democracy activist Vladimir Kara-Murza writes for the Washington Post:

In the last elections they ever ran in, Indonesian dictator Suharto achieved 75 percent of the vote; Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak had 89 percent; Romanian Communist leader Nicolae Ceausescu mastered an impressive 98 percent. My friend Boris Vishnevsky, a leading opposition legislator in St. Petersburg, likes to point out that Ceausescu still had a 99 percent approval rating in December 1989, just one week before his trial (and subsequent execution). As all these victors found out in the end, the results of manipulated “elections” in authoritarian systems are a poor indicator of the actual state of public opinion.

U.S. President Donald Trump congratulated Putin on his victory, prompting a curt response from Republican U.S. Senator John McCain.

“An American president does not lead the Free World by congratulating dictators on winning sham elections,” McCain said in a statement.

Putin seems, at present, invulnerable, argues John Lloyd, senior research fellow at Oxford University’s Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism:

Putin seems, at present, invulnerable, argues John Lloyd, senior research fellow at Oxford University’s Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism:

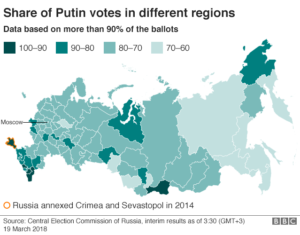

At a gathering of mainly young Russian liberals which I attended last weekend, Lev Gudkov, the veteran pollster and head of the independent Levada Centre, showed the graphs which underpin the success: a loss of popularity for Putin after his 2012 election and then, with the taking of Crimea and the Russian-sponsored hostilities in Ukraine, a huge spike upwards to some 80 percent of support, a doubling of the figures. In spite of declining incomes, rising prices and the viral videos showing the luxury in which senior officials live, Putin has stayed at or near these heights, unthinkable for a democratic politician. There has been, and remains, no alternative to Russia’s strongman.

In a series of probing analyses, New Eastern Europe charts the prospects for Vladimir Putin, who was re-elected for a fourth term as president on 18 March and has now been in power longer than Leonid Brezhnev, Eurozine adds:

In a series of probing analyses, New Eastern Europe charts the prospects for Vladimir Putin, who was re-elected for a fourth term as president on 18 March and has now been in power longer than Leonid Brezhnev, Eurozine adds:

No way out? Mark Galeotti detects a sense of weariness – and not just among ordinary Russians: ‘The talk in Moscow is that Putin is bored with ruling Russia. This is reinforced by his lacklustre demeanour in public appearances as well as the minimalist nature of his election campaign.’

New vision required: Konstantin Eggert turns a light on a major dilemma of Russia’s beleaguered opposition: Putin’s successful monopolization of foreign policy. Opponents can highlight corruption all they like, but ‘as soon as the critics of the Kremlin refuse to discuss Russia’s relations with the outside world, they immediately become ordinary soldiers of Putin’. However, Eggert predicts that ‘Putin’s fourth term will be a time of simmering political crisis that will eventually burst into the open’. The key to a successful outcome will be someone piercing today’s stagnation with ‘an attractive and realistic picture of the future’.

The defining feature of Russia’s 2018 presidential vote was that it was an election without choice, Kara-Murza adds:

The defining feature of Russia’s 2018 presidential vote was that it was an election without choice, Kara-Murza adds:

Two major opposition figures who had planned to run against Putin were absent from the ballot on Sunday. Boris Nemtsov, former deputy prime minister and leader of the People’s Freedom Party, was shot and killed in February 2015 on a bridge in front of the Kremlin. Alexei Navalny, a prominent anti-corruption campaigner, was barred from running, thanks to a trumped-up Russian court sentence that was assessed by the European Court of Human Rights as “arbitrary.”

Most Russians only remember Nemtsov as an opposition leader who organized popular demonstrators against Putin’s autocratic regime, says Stanford University’s Michael McFaul (a former Reagan-Fascell fellow at the National Endowment for Democracy). But I knew him for nearly two decades in a different role, when he was a popular, successful, democratically elected governor in Nizhny Novgorod, he writes for the Washington Post.

Most Russians only remember Nemtsov as an opposition leader who organized popular demonstrators against Putin’s autocratic regime, says Stanford University’s Michael McFaul (a former Reagan-Fascell fellow at the National Endowment for Democracy). But I knew him for nearly two decades in a different role, when he was a popular, successful, democratically elected governor in Nizhny Novgorod, he writes for the Washington Post.

“Nemtsov boldly pursued radical economic reforms in that role, yet managed to maintain popular support and protect his reputation. I also remember First Deputy Prime Minister Nemtsov, who challenged the oligarchs and made tackling corruption one of his highest priorities. He had the skills and charisma to have become a successful president – a successful democratic president,” McFaul adds, in an excerpt from his forthcoming book, “From Cold War to Hot Peace: An American Ambassador in Putin’s Russia” (May 2018):