Social media is neither inherently democratic or undemocratic, “but simply an arena in which political actors — some which may be democratic and some which may be anti-democratic — can contest for power and influence,” a new report suggests (In 2010, the Journal of Democracy featured an article about social media entitled “Liberation technology.” By 2017, the same journal was running “Can democracy survive the Internet?“), IJNet notes.

Hewlett

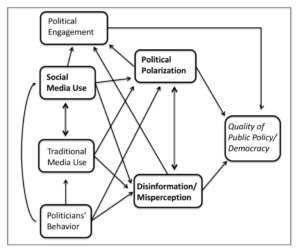

The report, released this week by the philanthropic Hewlett Foundation, “Social media, political polarization, and political disinformation: A review of the scientific literature.” The review of the literature is provided in six separate sections, that cumulatively are intended to provide an overview of what is known—and unknown—about the relationship between social media, political polarization, and disinformation, Hewlett adds. These six sections include:

- Online Political Conversations

- Consequences of Exposure to Disinformation Online

- Producers of Disinformation

- Strategies and Tactics of Spreading Disinformation

- Online Content and Political Polarization

- Misinformation, Polarization, and Democracy

The United States has been the victim of repeated cyberattacks by foreign powers, and it seems to have little power to stop them, according to Michael Sulmeyer, director of the Cyber Security Project at the Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center.

Hewlett

There are three main problems with U.S. efforts at cyber-deterrence, he writes for Foreign Affairs:

- The first is that Washington is trying to use a cold war strategy to address a twenty-first-century problem. History teaches that deterrence kept the Cold War cold: the United States and the Soviet Union were each vulnerable to the other’s thousands of nuclear weapons. When it comes to cyberspace, however, the United States has more to lose than its adversaries because it has gone further in embracing innovation and connectivity without security. But although the societies and infrastructure of Washington’s adversaries are less connected and vulnerable than those of the United States, their methods of hacking can still be disrupted.

- Second, it is difficult to convince foreign leaders (and foreign hackers) that the costs of hacking really do outweigh the benefits. Deterrence is all about perception: does an actor believe that the threat of punishment is real enough to prevent him from acting? This is as much a question of psychology as one of national security strategy. Many U.S. adversaries are less vulnerable in cyberspace than the United States is, so meaningful punishment would require discerning their priorities (for instance, money or public reputation) and threatening concerted action . ……

- Third, it is virtually impossible to know if deterrence is working. The goal is to prevent attacks. But if no attacks occur, it is hard to determine why—perhaps the would-be attacker was deterred by the threat of punishment; perhaps the attack failed for some other reason. Washington should not base its national cyberpolicy on a strategy whose success, almost by definition, cannot be evaluated, especially if there are good alternatives available. RTWT

As behavioral technologies emerge at the core of cyber-ops, “we will have to work harder to keep these trends from affecting the everyday life of our democratic society,” argues NYU professor Tamsin Shaw. That will mean paying closer attention to the military and civilian boundaries being crossed by the private companies that undertake such cyber-operations, she writes for the New York Review of Books:

As behavioral technologies emerge at the core of cyber-ops, “we will have to work harder to keep these trends from affecting the everyday life of our democratic society,” argues NYU professor Tamsin Shaw. That will mean paying closer attention to the military and civilian boundaries being crossed by the private companies that undertake such cyber-operations, she writes for the New York Review of Books:

From social media we should demand, at a minimum, much greater protection of our data. Over time, we might also see a lower tolerance for platforms whose business model relies on the collection and commercial exploitation of that data. As for politics, rather than elected officials’ perfecting technologies that give them access to personal information about the electorate, their focus should be on informing voters about their policies and actions, and making themselves accountable.

Russia continues to exploit the transparency essential to democracy in waging political warfare, analysts LeAnne N. Howard and Derek Reveron write for the National Interest:

Russia continues to exploit the transparency essential to democracy in waging political warfare, analysts LeAnne N. Howard and Derek Reveron write for the National Interest:

Russia can paralyze the politics in NATO member states to undermine the alliance. For its part, NATO seems fixated on the benchmark of defense spending at 2 percent of GDP to deter a Russian conventional attack. This conventional paradigm ignores the cognitive challenge that Russia pursues to weaken NATO from within. NATO must build on its whole-of-nation approaches, public-private partnerships and fledgling cyber capabilities to overcome its eclipsing bias of seeing the Russian threat as one of aircraft and tanks to one of malware and spies.

This isn’t your father’s Cold War: Russia has been very effective at leveraging and gaming the loopholes and contradictions of the liberal order to advance their interest, say Brookings analysts Alina Polyakova and Benjamin Haddad.

This isn’t your father’s Cold War: Russia has been very effective at leveraging and gaming the loopholes and contradictions of the liberal order to advance their interest, say Brookings analysts Alina Polyakova and Benjamin Haddad.

“Building Western resilience demands that we have an honest look at our systems, and address the weaknesses that have been so flagrantly exploited,” they contend. “The same way Russian electoral interference depends on the very real grievances of voters, brazen Russian behavior on Western soil is ultimately possible because we haven’t closed the door to their kleptocratic elites.”

The pro-Kremlin disinformation machine has been steaming at full speed in the past two weeks, as it has continued to deliver contradictory theories over the poisoning of Russian ex-spy Sergei Skripal, the EU East StratCom Task Force’s Disinformation Review reports (above). Pro-Kremlin disinformation claims the ex-spy poisoning was staged by the UK, or it was the US – and the motive must have been Russophobia. See the debunks here.

The pro-Kremlin disinformation machine has been steaming at full speed in the past two weeks, as it has continued to deliver contradictory theories over the poisoning of Russian ex-spy Sergei Skripal, the EU East StratCom Task Force’s Disinformation Review reports (above). Pro-Kremlin disinformation claims the ex-spy poisoning was staged by the UK, or it was the US – and the motive must have been Russophobia. See the debunks here.

The Kremlin has spent billions on an ambitious nationwide exhibition to promote its version of Russia’s history to schoolchildren, Coda Story adds.

As well as fake news, Russian media now cite fake election observers, Stop.Fake.org reports.

The so-called European Council on Democracy and Human Rights website may look legitimate at first glance, but a few clicks reveals irregularities, Polygraph reports. For example, there is a section under “projects” about Russian presidential election monitoring, but nothing about the regional elections they supposedly observed in September 2017. The ECDHR also lists no methodology for how it observes elections. Legitimate election monitoring organizations typically spend more time in the country prior to and after the election, and typically write detailed reports explaining their methodology and

The so-called European Council on Democracy and Human Rights website may look legitimate at first glance, but a few clicks reveals irregularities, Polygraph reports. For example, there is a section under “projects” about Russian presidential election monitoring, but nothing about the regional elections they supposedly observed in September 2017. The ECDHR also lists no methodology for how it observes elections. Legitimate election monitoring organizations typically spend more time in the country prior to and after the election, and typically write detailed reports explaining their methodology and  findings. For example, one can look at this field guide for election monitors from the National Democratic Institute [a core institute of the National Endowment for Democracy].

findings. For example, one can look at this field guide for election monitors from the National Democratic Institute [a core institute of the National Endowment for Democracy].

The Kremlin Watch Program at the European Values Think-Tank aims to create expert pressure for joint actions against Russian hostile activities.”We believe that it is high time for Western governments to start taking seriously the threat posed by Russia and respond to the Kremlin’s increasingly audacious aggression with resolute diplomatic and counter-intelligence measures,” says its Open Call. To co-sign, add your details here.