This Sunday, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban is set to win another term in national elections, giving him a fresh mandate to advance his project of building what he calls an “illiberal” state at the heart of Europe, says Alex Kliment of GZERO Media. Over the past eight years, Orban’s democratically-elected governments have, in fact, behaved less and less democratically — steadily centralizing power, eroding the independence of the courts, the media, and even cultural institutions, he writes for AXIOS.

This Sunday, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban is set to win another term in national elections, giving him a fresh mandate to advance his project of building what he calls an “illiberal” state at the heart of Europe, says Alex Kliment of GZERO Media. Over the past eight years, Orban’s democratically-elected governments have, in fact, behaved less and less democratically — steadily centralizing power, eroding the independence of the courts, the media, and even cultural institutions, he writes for AXIOS.

Why it matters

With each new term won by Fidesz, Hungary’s ruling party, its hold on power is becoming more entrenched, notes Dalibor Rohac, a research fellow at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, D.C. That includes the party’s financial backing by a network of oligarchs who are awarded an overwhelming proportion of government contracts, usually involving EU funds, but also the presence of party loyalists at all levels of government administration and the judiciary—not to speak of public broadcasting and the fact that the vast majority of media outlets are owned by Fidesz supporters, he writes for the Weekly Standard.

It is sad that Hungary has now come to a place where an Orwellian-sounding slogan, “System of National Cooperation,” redolent of Mussolini’s rhetoric, is the official governing philosophy; where the premier can brag that he is building an alternative to western liberal democracy; and, where Orbán, having in his youth led the call for Soviet occupation forces to exit the country, now acts as one of Vladimir Putin’s best advocates inside NATO and the European Union, notes Thomas O. Melia, a former Deputy Assistant Secretary of State and Assistant Administrator of USAID.

It is sad that Hungary has now come to a place where an Orwellian-sounding slogan, “System of National Cooperation,” redolent of Mussolini’s rhetoric, is the official governing philosophy; where the premier can brag that he is building an alternative to western liberal democracy; and, where Orbán, having in his youth led the call for Soviet occupation forces to exit the country, now acts as one of Vladimir Putin’s best advocates inside NATO and the European Union, notes Thomas O. Melia, a former Deputy Assistant Secretary of State and Assistant Administrator of USAID.

So sad, in fact – he writes for the American Interest – that I have found myself this week signing on to a “Statement of Principles” drawn up by an impromptu gathering, convened at the Bipartisan Policy Center, including former legislators and government officials, Republicans and Democrats and independents, scholars, journalists, and activists who care about the fate of democracy in Europe. As the statement makes clear, we “come together out of alarm that the erosion of democratic principles and weakening of democratic institutions among some of our European allies is putting at risk U.S. peace, security, and prosperity,” adds Melia, a fellow at the George W. Bush Institute and a senior fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute.

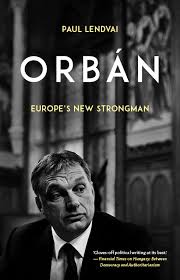

Like other populist leaders, Orbán presents his government as being based on direct democracy (on account of the frequent, highly manipulative “national consultations”) in contrast to what he dismisses as “liberal nondemocracy,” observes Princeton professor Jan-Werner Müller, author of What Is Populism? Some critics have called Hungary fascist, but the system is clearly not—after all, the government does not seek to mobilize people, encourage mass violence, or demand total ideological conformity, he writes for the NYRB in a review of Paul Lendvai’s Orbán: Hungary’s Strongman:

Like other populist leaders, Orbán presents his government as being based on direct democracy (on account of the frequent, highly manipulative “national consultations”) in contrast to what he dismisses as “liberal nondemocracy,” observes Princeton professor Jan-Werner Müller, author of What Is Populism? Some critics have called Hungary fascist, but the system is clearly not—after all, the government does not seek to mobilize people, encourage mass violence, or demand total ideological conformity, he writes for the NYRB in a review of Paul Lendvai’s Orbán: Hungary’s Strongman:

In the end, Lendvai settles on the term “Führer democracy” to emphasize the extraordinary centralization of power in the Viktator’s hands. And he endorses the idea of the “mafia state,” a term coined by the Hungarian sociologist Bálint Magyar to suggest that the reign of Fidesz has little to do with political ideas, but is simply a means for a “political family” to plunder the country under the protection of its godfather. Lendvai’s characterization of Orbán as capable of adopting any belief according to political expediency chimes with that interpretation.

In the end, Lendvai settles on the term “Führer democracy” to emphasize the extraordinary centralization of power in the Viktator’s hands. And he endorses the idea of the “mafia state,” a term coined by the Hungarian sociologist Bálint Magyar to suggest that the reign of Fidesz has little to do with political ideas, but is simply a means for a “political family” to plunder the country under the protection of its godfather. Lendvai’s characterization of Orbán as capable of adopting any belief according to political expediency chimes with that interpretation.

Magnitsky-like sanctions would offer the U.S. the opportunity to harmonize concerns regarding democratic backsliding in NATO and the E.U. with more hardline policies toward authoritarianism outside Europe, argues Melissa Hooper, Director of Human Rights and Civil Society at Human Rights First. And as far-right parties gain troubling footholds further and further west, like Alternative für Deutschland in Germany, champions of liberalism have a powerful incentive to cooperate with one another. Curbing Hungarian kleptocrats may be one move everyone can agree on, she writes for the New Republic.

An embarrassment is that the EU hasn’t been more effective at blocking Mr. Orban’s authoritarian moves, the Wall Street Journal adds. Mr. Orban has been shrewd in befriending political groups in Brussels, and the EU doesn’t have much authority to punish countries determined to stray from democracy. That leaves Hungarian voters to defend their democracy as best they can, while they can.