Russian intrusions into democratic institutions around the world have been in the spotlight for some time. But as a recent letter from a bipartisan group of US senators warns, China is also getting into the business of interfering in democracies through the exertion of what might be called “sharp power,” argues Christopher Walker, vice-president for studies and analysis at the National Endowment for Democracy. The authoritarian regimes in China and Russia are preying on the openness of democracies. And this situation presents challenges distinct from the cold war era, which did not afford autocrats so many opportunities for action within democratic societies, he writes for the Financial Times:

Russian intrusions into democratic institutions around the world have been in the spotlight for some time. But as a recent letter from a bipartisan group of US senators warns, China is also getting into the business of interfering in democracies through the exertion of what might be called “sharp power,” argues Christopher Walker, vice-president for studies and analysis at the National Endowment for Democracy. The authoritarian regimes in China and Russia are preying on the openness of democracies. And this situation presents challenges distinct from the cold war era, which did not afford autocrats so many opportunities for action within democratic societies, he writes for the Financial Times:

As long as China and Russia remain unfree societies in which independent institutions are unable to hold the leadership accountable, their authoritarian regimes will continue to exert sharp power. Democracies must draw upon their reserves of innovation and determination as free societies to meet this formidable challenge.

This week’s Brussels Summit comes at a time when NATO and many of its member states are under attack, facing an assault not on their territory but on the democratic institutions that are the foundation of the Alliance itself, notes Laura Rosenberger, Senior Fellow and Director of the Alliance for Securing Democracy.

This week’s Brussels Summit comes at a time when NATO and many of its member states are under attack, facing an assault not on their territory but on the democratic institutions that are the foundation of the Alliance itself, notes Laura Rosenberger, Senior Fellow and Director of the Alliance for Securing Democracy.

“Asymmetric tactics — including information operations, cyber-attacks, malign financial influence, economic coercion, and subversion of political and social groups — are used by adversaries not just to undermine individual democratic states but also to sow discord in NATO,” she adds. “Responding meaningfully to these crosscutting tactics requires political will from the top, whole-of-government efforts, and a united transatlantic response,” she contends:

“Asymmetric tactics — including information operations, cyber-attacks, malign financial influence, economic coercion, and subversion of political and social groups — are used by adversaries not just to undermine individual democratic states but also to sow discord in NATO,” she adds. “Responding meaningfully to these crosscutting tactics requires political will from the top, whole-of-government efforts, and a united transatlantic response,” she contends:

NATO can build on the agreement at the recent G7 to establish a mechanism for sharing information on threats and best practices, and for coordination with the private sector, particularly tech companies. Given the nature of the threats, coordination with the EU will be essential. The two institutions should build on their agreement at the 2016 Warsaw Summit to enhance cooperation on hybrid and cyber threats by establishing a joint NATO–EU task force on these issues to better coordinate activity that falls across their respective bureaucracies.

When it comes to digital disinformation, at least four dimensions must be considered, argues Kelly Born, a program officer for the Madison Initiative at the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation.

When it comes to digital disinformation, at least four dimensions must be considered, argues Kelly Born, a program officer for the Madison Initiative at the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation.

- First, whois sharing the disinformation? Disinformation spread by foreign actors can be treated very differently – both legally and normatively – than disinformation spread by citizens, particularly in the United States, with its unparalleled free-speech protections and relatively strict rules on foreign interference….

- Second, whyis the disinformation being shared? “Misinformation” – inaccurate information that is spread unintentionally – is quite different from disinformation or propaganda, which are spread deliberately. Preventing well-intentioned actors from unwittingly sharing false information could be addressed, at least partly, through news literacy campaigns or fact-checking initiatives. Stopping bad actors from purposely sharing such information is more complicated, and depends on their specific goals.

Third, how is the disinformation being shared? If actors are sharing content via social media, changes to platforms’ policies and/or government regulation could be sufficient. But such changes must be specific….Yet digital platforms cannot manage disinformation alone, not least because, by some estimates, social media account for only around 40% of traffic to the most egregious “fake news” sites, with the other 60% arriving “organically” or via “dark social” (such as messaging or emails between friends). These pathways are more difficult to manage.

Third, how is the disinformation being shared? If actors are sharing content via social media, changes to platforms’ policies and/or government regulation could be sufficient. But such changes must be specific….Yet digital platforms cannot manage disinformation alone, not least because, by some estimates, social media account for only around 40% of traffic to the most egregious “fake news” sites, with the other 60% arriving “organically” or via “dark social” (such as messaging or emails between friends). These pathways are more difficult to manage.- The final – and perhaps the most important – dimension of the disinformation puzzle is: whatis being shared? Experts tend to focus on entirely “fake” content, which is easier to identify. But digital platforms naturally have incentives to curb such content, simply because people generally do not want to look foolish by sharing altogether false stories.

“People do, however, like to read and share information that aligns with their perspectives; they like it even more if it triggers strong emotions – especially outrage,” Born writes for Project Syndicate. “Such content is not just polarizing; it is often misleading and incendiary, and there are signs that it can undermine constructive democratic discourse.”

“People do, however, like to read and share information that aligns with their perspectives; they like it even more if it triggers strong emotions – especially outrage,” Born writes for Project Syndicate. “Such content is not just polarizing; it is often misleading and incendiary, and there are signs that it can undermine constructive democratic discourse.”

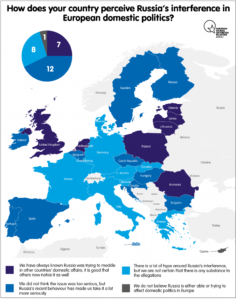

In recent months, much ink has been spilled in warning about

Credit: ECFR

the specter of Putinism and a nascent ‘Reactionary international’ haunting Europe, says analyst Evgeny Pudovkin. And yet, for all the talks regarding Eurogeddon, there are several reasons to doubt the gloomiest of doomsayers’ prognosis, he writes for New Eastern Europe:

First, the impact of Russia’s disinformation campaign has been limited at best. The Kremlin can Troll Western powers. Disrupt European politics, not so much. Although malevolent, Moscow’s interventions, as several case studies might attest, hardly had any considerable impact on any elections. And with Western intelligence coming to grips with tools of Russia’s disinformation, it will soon learn to tackle this problem at little cost.

Russia’s World Cup win over Spain echoes Moscow’s recent successes over Western allies in another international competition, that of power and influence. Instead of offering innovative solutions to geopolitical challenges, liberal democracies passively rely on their system of superior values to prevail, argues Eguiar Lizundia, Senior Governance Specialist at the International Republican Institute. Just as Spain’s tiki-taka was clearly better than Russia’s defensive style but could not deliver a win, liberal democratic leaders have remained reflexive to the rise of authoritarianism, believing that the trend towards democratization was unbeatable in the long-term, he contends:

Russia’s World Cup win over Spain echoes Moscow’s recent successes over Western allies in another international competition, that of power and influence. Instead of offering innovative solutions to geopolitical challenges, liberal democracies passively rely on their system of superior values to prevail, argues Eguiar Lizundia, Senior Governance Specialist at the International Republican Institute. Just as Spain’s tiki-taka was clearly better than Russia’s defensive style but could not deliver a win, liberal democratic leaders have remained reflexive to the rise of authoritarianism, believing that the trend towards democratization was unbeatable in the long-term, he contends:

With the exception of notable efforts from the United States’ National Endowment for Democracy and its core institutes, including the International Republican Institute and development agencies of liberal democracies, these societies have lost interest in making freedom and democracy a core priority. In contrast, Russia and China have adopted a very assertive foreign policy—otherwise known as sharp power—that pro-actively promotes their illiberal model of society.