2009 Seymour Martin Lipset Lecture: Nathan Glazer from National Endowment for Democracy on Vimeo.

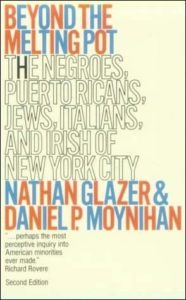

Nathan Glazer, a prominent sociologist and public intellectual who assisted on a classic study of conformity, “The Lonely Crowd,” and co-authored a groundbreaking document of non-conformity, “Beyond the Melting Pot,” has died at 95, AP reports:

A longtime professor at Harvard University, Glazer, was among the last of the deeply-read thinkers who influenced culture and politics in the mid-20th century. Starting in the 1940s, Glazer was a writer and editor for Commentary and The New Republic. He was a co-editor of The Public Interest, and wrote or co-wrote numerous books. With peers such as Daniel Bell and Irving Howe, he had a wide range of interests, “a notion of universal competence,” from foreign policy to Modernist architecture, subject of one his latter books, “From a Cause to a Style.”

Consideration of Glazer’s life and work “affords us the opportunity to glean insights about the deep popular disaffection with contemporary elites — intellectual and cultural as well as political — that is now roiling American society, and liberal democracies generally,” Peter Skerry wrote for National Affairs.

Consideration of Glazer’s life and work “affords us the opportunity to glean insights about the deep popular disaffection with contemporary elites — intellectual and cultural as well as political — that is now roiling American society, and liberal democracies generally,” Peter Skerry wrote for National Affairs.

Two groups of thinkers that have had a lasting impact on American culture had a lasting impact on Mr. Glazer as well, The Times adds:

- The first was the New York Intellectuals, the collection of writers, gathered around Partisan Review and later The New York Review of Books, who combined leftist politics with modernist aesthetics. …. Writers like James Baldwin and Irving Howe would drop by the office, and at Greenwich Village parties he met prominent intellectuals like Lionel Trilling and the Partisan Review editors Philip Rahv and William Phillips. …

- Glazer’s turn to neoconservatism followed an almost paradigmatic path. Throughout the 1950s, and even after he went to work for the Kennedy administration’s Housing and Home Finance Agency in 1962-63, he continued to consider himself a radical. But if, as his longtime friend Irving Kristol put it, a neoconservative is a liberal who has been mugged by reality, then Mr. Glazer got hit over the head.

But Mr. Glazer drifted only as far as the political center, the Journal’s Jason Winnick adds. Sometimes labeled a “neoconservative,” like Kristol or Norman Podhoretz, he says he’s never voted Republican except once in Massachusetts, as a protest against “the fact that some Kennedy was being elected from the district again and again.”

But Mr. Glazer drifted only as far as the political center, the Journal’s Jason Winnick adds. Sometimes labeled a “neoconservative,” like Kristol or Norman Podhoretz, he says he’s never voted Republican except once in Massachusetts, as a protest against “the fact that some Kennedy was being elected from the district again and again.”

Alongside Irving Howe, Irving Kristol, and Daniel Bell, Glazer featured in Arguing the World, a film and book chronicling the political trajectory of the New York Intellectuals:

Although Marxists during the 30s, by the Cold War these men were strongly anti-Communist. But they also opposed Senator Joseph McCarthy’s witch-hunts, and thus were at odds with both the radical right and the radical left.

His experiences in government bureaucracy in the early 1960s and later as a professor at Berkeley amid the student revolts made him skeptical of social change imposed without sufficient respect for existing institutions. His criticism of ambitious government planning was rooted in his respect for traditional ways of life, The Wall Street Journal adds:

“Every piece of social policy substitutes for some traditional arrangement, whether good or bad, a new arrangement in which public authorities take over, at least in part, the role of the family, of the ethnic and neighborhood group, or of the voluntary association. In doing so, social policy weakens the positions of these traditional agents,” he wrote in “The Limits of Social Policy” for Commentary magazine. “Perhaps this is the basic force behind the ever growing demand for social policy, and its frequent failure to satisfy the demand.”

“Every piece of social policy substitutes for some traditional arrangement, whether good or bad, a new arrangement in which public authorities take over, at least in part, the role of the family, of the ethnic and neighborhood group, or of the voluntary association. In doing so, social policy weakens the positions of these traditional agents,” he wrote in “The Limits of Social Policy” for Commentary magazine. “Perhaps this is the basic force behind the ever growing demand for social policy, and its frequent failure to satisfy the demand.”

In the annual Seymour Martin Lipset Lecture on Democracy in the World (above), Glazer considered how democracies deal with deep divides—ineradicable divisions such as race, ethnicity, religion, and language. Drawing on the experience of Canada and India (with side observations on the U.S.), he posited in the NED’s Journal of Democracy that free political parties competing for votes, including minorities’ votes, are a key factor in moderating divides and in bringing forth measures that produce a degree of stability—firm in Canada, shakier in India.

Glazer co-founded and co-edited the journal The Public Interest, with Kristol.

Although The Public Interest is remembered as an influential conservative magazine, its story began on the left. Irving Kristol and Daniel Bell met in the 1930s in the radical precincts of the student body of the City College of New York — the “Harvard of the proletariat,” Adam Keiper writes for National Affairs:

In the City College lunchroom, “an especially slummy and smelly place,” as Kristol later recounted, were about a dozen alcoves into which students would gather at lunchtime and between classes, generally segregating themselves by religion and race and ideology. Alcove No. 2 was home to those communists who believed Stalinism remained the hope of the future. The much smaller gaggle of Marxist radicals who opposed Stalin met in Alcove No. 1. As was routine on the far left, this group was endlessly splintering into grouplets. Kristol was then a Trotskyist; Bell, a social democrat. They and numerous other future editors and academics — Irving Howe, Nathan Glazer, Philip Selznick, Seymour Martin Lipset, Melvin Lasky, and more — cut their teeth in Alcove No. 1.

If Irving was a critic of liberalism, it was because he appreciated liberalism’s strengths and wished to protect it from its worst inclinations, Adam Wolfson writes for The American Interest. Nat was skeptical of what social policy could achieve, and wary of its unintended consequences for individuals, families, and society. When it came to social policy, he was a follower of the Hippocratic Oath—that first, one must do no harm.