With the re-emergence of great power competition, Russia and China are pursuing asymmetric strategies against the West, using the advantages of authoritarianism—secrecy, deception, a lack of legal or moral constraints—to launch sophisticated political warfare campaigns that exploit the openness of democratic societies, according to Hal Brands, the Henry Kissinger Distinguished Professor at Johns Hopkins University, School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS).

With the re-emergence of great power competition, Russia and China are pursuing asymmetric strategies against the West, using the advantages of authoritarianism—secrecy, deception, a lack of legal or moral constraints—to launch sophisticated political warfare campaigns that exploit the openness of democratic societies, according to Hal Brands, the Henry Kissinger Distinguished Professor at Johns Hopkins University, School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS).

“Russia is using low-cost tools such as political warfare and cyber operations to impose high costs on its adversaries,” he observes. “It is generally more expensive to defend against cyberattacks than to conduct them…. and the Kremlin’s strategy shows how targeted investments can exact a high price in terms of political rancor and social instability.”

The West must therefore recommit to identifying and exploiting its own asymmetric advantages, he writes in The Lost Art of Long-Term Competition, an article for the Washington Quarterly:

The West must therefore recommit to identifying and exploiting its own asymmetric advantages, he writes in The Lost Art of Long-Term Competition, an article for the Washington Quarterly:

It might explore, as defense analyst Evan Montgomery suggests, using its unmatched array of alliances and partnerships to confront China and Russia with new dilemmas, such as security threats that emerge from unexpected directions. It might take advantage of another asymmetric advantage—the contrast between democratic values and authoritarian repression—to better expose the ideological and political weaknesses of regimes that do not rest on the freely given consent of the governed.

Liberal democracies have their own advantages to exploit, not least through civil society engagement. Simply “[introducing] new information into relatively closed societies … can be a method of competition that imposes significant costs on regimes that constantly worry about maintaining domestic control,” analysts Thomas G. Mahnken, Ross Babbage, Toshi Yoshihara argue in Countering Comprehensive Coercion: Competitive Strategies Against Authoritarian Political Warfare.

Liberal democracies have their own advantages to exploit, not least through civil society engagement. Simply “[introducing] new information into relatively closed societies … can be a method of competition that imposes significant costs on regimes that constantly worry about maintaining domestic control,” analysts Thomas G. Mahnken, Ross Babbage, Toshi Yoshihara argue in Countering Comprehensive Coercion: Competitive Strategies Against Authoritarian Political Warfare.

“Targets of authoritarian political warfare campaigns can better position themselves to compete, not only by reducing their vulnerability but also by adopting more forward-leaning measures of their own,” they contend.

The rise of the digital techno-giants and the threat of global cyber warfare has upset the foundations of democracy, a Davos forum heard this week. Liberal nations may be forced to retreat behind defensive barriers of “techno-sovereignty”, shutting down the cross-border flows of data and information we all take for granted. The global tech war threatens the ‘Westphalian order’ and liberal democracy, said US General John Rutherford Allen, a former Nato commander and ex-head of the global anti-Isil coalition.

The rise of the digital techno-giants and the threat of global cyber warfare has upset the foundations of democracy, a Davos forum heard this week. Liberal nations may be forced to retreat behind defensive barriers of “techno-sovereignty”, shutting down the cross-border flows of data and information we all take for granted. The global tech war threatens the ‘Westphalian order’ and liberal democracy, said US General John Rutherford Allen, a former Nato commander and ex-head of the global anti-Isil coalition.

The end of the unipolar moment and the return of great power competition change the cost-benefit structure for U.S. engagement, Foreign Policy Research Institute analyst Nikolas Gvosdev writes in Selective Engagement: A Bipartisan U.S. Foreign Policy Approach?; as Nadia Schadlow, who served as deputy national security advisor in the Trump administration, notes, the U.S. government, in crafting a foreign policy, must

respond to key shifts in the geopolitical order, including the resurgence of great power competition, to acknowledge limitations in American power and agency and to modernize U.S. engagement with other countries and institutions.

A calendar of likely Kremlin subversion in Europe can help policy planners in Western capitals to monitor and counter the likely assaults, says CEPA analyst Janusz Bugajski:

Above all, Moscow will seek to benefit from the Brexit fallout, the European parliamentary elections, and from perceptions of uncertainty over NATO’s future. The repercussions of Brexit, with or without a final agreement between London and Brussels, could prove damaging for European solidarity …

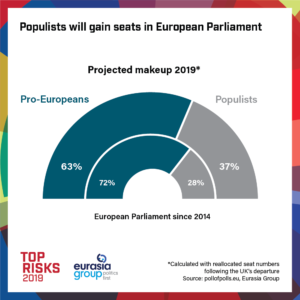

Eurasia Group

EU parliamentary elections in 27 states between May 23 and 26 will also test the degree of disillusionment with the Union and help determine policy directions for the next five years.

Several opinion polls have projected an assortment of right and left populists and other Euroskeptics gaining 20 percent of the vote for the 705-member parliament….

A third pan-European pressure point for Moscow is to disseminate uncertainty about the future of NATO. ….

Kremlin policy is also geared toward more specific opportunities in key elections in several neighboring states. Moldova’s parliamentary elections on 24 February is the first in line..

Competition in the ideological realm [what a National Endowment for Democracy report calls ‘sharp power‘] is already a major component of contemporary rivalry, with Russia and China arguing that their versions of authoritarian capitalism are superior to liberal democracy in meeting the material and spiritual needs of their respective citizenries, adds Brands, co-author, with Charles Edel, of The Lessons of Tragedy: Statecraft and World Order:

In an effort to enhance their geopolitical influence and make the world safe for autocracy, both countries are also working to strengthen fellow authoritarian regimes, promote illiberal norms such as “Internet Sovereignty” (the idea that countries should be able to exercise exclusive control of their cyberspace in the same way they can restrict their airspace), undermine Western conceptions of human rights and good governance, and corrupt or manipulate democratic systems in the United States and other countries.

In an effort to enhance their geopolitical influence and make the world safe for autocracy, both countries are also working to strengthen fellow authoritarian regimes, promote illiberal norms such as “Internet Sovereignty” (the idea that countries should be able to exercise exclusive control of their cyberspace in the same way they can restrict their airspace), undermine Western conceptions of human rights and good governance, and corrupt or manipulate democratic systems in the United States and other countries.

To refrain from taking up the ideological struggle, then, would amount to unilateral disarmament, Brands contends:

By underscoring the contrast between authoritarianism and democracy, by backing democratic forces abroad and defending democratic values at home, and by assisting those who criticize or seek to leaven the illiberal elements of Russian and Chinese rule, the United States can make the most of a fundamental competitive asymmetry. Few approaches are better suited to long-term competition than that. RTWT