Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini betrayed the principles of the Iranian revolution after sweeping to power in 1979, leaving a “very bitter” taste among some of those who had returned with him to Tehran in triumph, his first president told Reuters:

Abolhassan Bani-Sadr, a sworn opponent of Tehran’s clerical rulers ever since being driven from office and fleeing abroad in 1981, recalled how 40 years ago in Paris, he had been convinced that the religious leader’s Islamic revolution would pave the way for democracy and human rights after the rule of the Shah.

“When we were in France everything we said to him he embraced and then announced it like Koranic verses without any hesitation,” Bani-Sadr, now 85, said in an interview at his home in Versailles, outside Paris, where he has lived since 1981. “We were sure that a religious leader was committing himself and that all these principles would happen for the first time in our history,” he said…..

“France was the crossroads of ideas and information, which is why he picked it after Kuwait refused to take him,” Bani-Sadr said. “When he was in France he was on the side of freedom. He was scared that the movement wouldn’t reach its conclusion and he’d be forced to stay there.”

In fact, Khomeini had his mind set on total power, notes analyst Sohrab Ahmari. By the end of its first decade, the Islamic Republic had dismantled labor unions, banned opposition, shuttered newspapers and summarily executed thousands, including many of its erstwhile leftist allies, he writes for the Wall Street Journal.

“When he returned to #Iran in 1979, Ayatollah Khomeini made lots of promises to the Iranian people, including justice, freedom, and prosperity. 40 years later, Iran’s ruling regime has broken all those promises, and has produced only #40YearsofFailure,” the US State Department wrote on its official Twitter account.

Iran’s revolution shook the world in 1979. Forty years later, Brookings experts Suzanne Maloney and Bruce Riedel look back on the rise of the Islamic Republic and explore what the revolution means for today’s volatile Middle East and U.S. relations with Iran (above).

Misagh Parsa explain s the huge irony that lurks at the heart of the Islamic Republic in his book, Democracy in Iran: Why It Failed and How It Might Succeed (see below), notes Ladan Boroumand. Khomeini (1902–89), rode to power in 1979 at the head of a large and inclusive coalition. His supporters came from many backgrounds and represented a range of ideological inclinations, she writes for the Journal of Democracy:

Yet Khomeini’s rule unleashed an implacable dynamic of exclusion that was inherent in his theocratic project. Once he took over, exclusionary wave followed exclusionary wave. The non-Islamist elements of his coalition were the first to go. Then the revolution began to eat its own, as Khomeini purged hard-core Islamists who had been among the very architects of the theocratic regime, but who had become political liabilities.

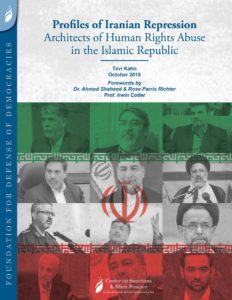

Thirteen months later, the Iranian uprising has shown remarkable endurance, notes Tzvi Kahn, a senior Iran analyst at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, a Washington-based nonpartisan research institute focusing on national security and foreign policy.

Although Western reporting about the demonstrations largely faded within weeks, protests continued throughout 2018. Dozens of rallies have already occurred this year. Yet unlike other revolts in the Middle East, which rapidly subsided, descended into civil war, or — as in the case of Egypt and Tunisia — resulted in swift regime change, Iran’s unrest persists in a state of apparent deadlock, he writes for the National Review.

Whether by coercion or negotiation, Iran’s political factions have been unable to stem the tide of social protest rising for the past several years, say UCLA analysts Kevan Harris and Zep Kalb. As with previous upsurges in post-revolutionary Iran, such popular mobilization tends to widen the cracks in elite competition within the country’s political establishment. As these political factions jockey against each other, draw new lines of competition and attempt to mobilize popular support in upcoming political contests, popular disruption from below may create spaces where Iran’s political establishment will be forced to react in surprising ways yet again, they write for the Post’s Monkey Cage blog.

Whether by coercion or negotiation, Iran’s political factions have been unable to stem the tide of social protest rising for the past several years, say UCLA analysts Kevan Harris and Zep Kalb. As with previous upsurges in post-revolutionary Iran, such popular mobilization tends to widen the cracks in elite competition within the country’s political establishment. As these political factions jockey against each other, draw new lines of competition and attempt to mobilize popular support in upcoming political contests, popular disruption from below may create spaces where Iran’s political establishment will be forced to react in surprising ways yet again, they write for the Post’s Monkey Cage blog.

Politicians do not rule out the possibility of more protests but urge caution, the FT reports.

“The collapse of a system can happen if there is insecurity or when it loses its control over the country’s affairs, none of which has happened in Iran,” says Hamid-Reza Taraghi, a politician close to hardline forces. “The gap between the political system and the people is not big; Iran’s military forces listen to political rulers and Iran has a thorough dominance of intelligence over the Middle East which even the US lacks.”

Iranian commentator Saeed Barzin said that “at the time of the revolution both secular and religious opposition thinking was deeply anti-freedom, anti-liberal and pro-despotism.” Some of the forces involved in the revolution had a Marxist idea about freedom, while Khomeini wanted a religious government, Radio Farda reports:

“The only moderate thought that supported freedom and democracy, was embodied in the administration of Prime Minister Mehdi Bazargan (first post-revolution prime minister), a mixture of leading members of the National Front and Freedom Movement liberal groups. Bazargan was the most important representative of liberal thought at that time,” Barzin said, adding, however, that the prominent ideology at the time was the idea of despotism.

“The only moderate thought that supported freedom and democracy, was embodied in the administration of Prime Minister Mehdi Bazargan (first post-revolution prime minister), a mixture of leading members of the National Front and Freedom Movement liberal groups. Bazargan was the most important representative of liberal thought at that time,” Barzin said, adding, however, that the prominent ideology at the time was the idea of despotism.

Another commentator, Reza Pirzadeh disagreed, saying: “The best person who at the time was able to defend freedom and democracy and push Iran toward liberal democracy was the Shah’s last prime minister Shapour Bakhtiar. Unfortunately the National Front and other national forces including Bazargan turned their back to Bakhtiar and preferred to get close to Khomeini and work with him.”

A new generation of civic-minded, courageous activists is rising in Iran, according to CIVICUS. Some Iranians have taken to social media to vent their anger at the clergy, circulating jokes on how backward the old clerics based in the holy city of Qom are in the face of modern issues, the FT adds:

“Iranians rightly see the root of their problems in mixing politics with religion,” says one cleric. “There is rising demand for separation of the two.” But a former reformist official warns that those seeking radical change will be disappointed: “Those who talk about the collapse of the Islamic Republic have very shallow knowledge of Iran and Shiism,” he says. “The resilience and pragmatism of the Shia clergy and Iranians will prevent a radical movement similar to the 1979 revolution.”

But Iran’s civil society activists and dissidents have been let down by the West, according to Mariam Memarsadeghi, co-founder and co-director of Tavaana: E-Learning Institute for Iranian Civil Society.

Credit: defendlawyers

What explains this callous lack of interest from the Free World in the plight of Iran and its people? Part of the answer can be divined from the accusations of “warmonger” that invariably greet anyone who draws attentions to the regime’s depredations, she writes for Quillette:

Claims like those I have made above, we are told, are simply a means of preparing the basis for another American war in the Middle East. But this thinking is as logically nonsensical as it is morally cowardly. Americans are understandably wary of military intervention after the experience of Iraq and the calamitous consequences of the “Arab Spring” in Egypt, Libya, Yemen, and Syria. But opposition to military intervention does not require anyone to deny the despotic reality of the Iranian revolutionary regime or to ignore its embattled victims.

“There are many ways that Western democrats can offer solidarity and support to the struggles of Iranians who yearn for the same freedoms they enjoy,” Memarsadeghi adds.

Forty civil society organizations including the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI) and partners of the National Endowment for Democracy recently signed a letter urging UN member states to act on human rights violations in Iran.

Forty civil society organizations including the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI) and partners of the National Endowment for Democracy recently signed a letter urging UN member states to act on human rights violations in Iran.

The collision of Khamenei’s creed with the imperatives of realpolitik has left Tehran in a straitjacket, says the FDD’s Kahn, a Fellow at the NED’s Penn Kemble Forum:

To address its people’s manifold demands, Iran would need to restore its ailing economy, end regime corruption, ameliorate water shortages, cease human-rights abuses, and roll back its regional aggression. But achieving these goals would require Tehran, at a minimum, to reconcile with the United States, embrace liberal norms, and become, as Secretary of State Mike Pompeo put it, a “normal country.”

“Herein lies the revolution’s fundamental contradiction,” he adds. “In order to survive, Tehran would need to deny its Islamist identity — the basis of its self-declared legitimacy. It would need to commit political suicide.”

The scholar Ervand Abrahamian has drawn attention—in several books, including Khomeinism: Essays on the Islamic Republic (1993)—to Khomeini’s borrowing of language like mostazafin (“the oppressed”) and rituals like May Day from the left. As the 1970s developed, Khomeini drew from Shariati a fusion of Leninist egalitarianism with Shi’ite Muslim mythology, former FT analyst Gareth Smyth observes. To present Khomeini as a fundamentalist, Abrahamian argues, is seriously wrong:

The scholar Ervand Abrahamian has drawn attention—in several books, including Khomeinism: Essays on the Islamic Republic (1993)—to Khomeini’s borrowing of language like mostazafin (“the oppressed”) and rituals like May Day from the left. As the 1970s developed, Khomeini drew from Shariati a fusion of Leninist egalitarianism with Shi’ite Muslim mythology, former FT analyst Gareth Smyth observes. To present Khomeini as a fundamentalist, Abrahamian argues, is seriously wrong:

…the term “fundamentalist” conjures up the image of inflexible orthodoxy, strict adherence to tradition, and rejection of intellectual novelty, especially from outside. In the political arena, however, Khomeini, despite his own denials, was highly flexible, remarkably innovative, and cavalier towards hallowed traditions. He is important precisely because he discarded many Shii concepts and borrowed ideas, words and slogans from the non-Muslim world. In doing so, he formulated a brand-new Shii interpretation of state and society.

The Islamic Republic’s egalitarianism has been shown in Kevan Harris’s 2017 book, “A Social Revolution: Politics and the Welfare State in Iran,” which demonstrated how state policies have extended health care, reduced poverty, “leveled life chances between town and country and fused together a nation-state far more intertwined than under the previous regime,” Smyth adds.

The resulting paternalism and public fear of insecurity may provide a cushion of protection for the regime, observers suggest.“Security remains a top priority for the middle class,” says Mohammad-Ali Abtahi, a former reformist vice-president arrested during the 2009 Green Movement unrest. “Iranians’ fear of turning into another Syria or Iraq plus the ruling system’s military might at home and in the region mean the Islamic Republic is nowhere near collapse.”