Authoritarianism has reemerged as the greatest threat to the liberal democratic world, and we have no idea how to confront it, Robert Kagan wrote in the first edition of The Opinions Essay — The Washington Post’s new long-form storytelling initiative. Washington Post Live brings together foreign policy leaders to address the breakdown of global alliances, the rise of nationalism and the ever-growing threat to democracy (above).

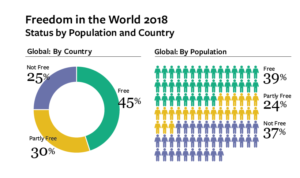

These are dark times for democracy, but you miss a large part of the picture if you don’t see the pushback. Despite the downward trends, however, countries are forming new alliances to put pressure on repressive regimes, notes Christian Science Monitor:

These are dark times for democracy, but you miss a large part of the picture if you don’t see the pushback. Despite the downward trends, however, countries are forming new alliances to put pressure on repressive regimes, notes Christian Science Monitor:

Human Rights Watch …points to the example of the EU and a group of Muslim-majority countries working together to create a mechanism at the U.N. to collect evidence on the ethnic cleansing of Rohingyas, which could be used in future trials of the Myanmar government. A group of Latin American countries led a resolution in the Human Rights Council to condemn the severe persecution of Venezuelans under President Nicolás Maduro.

Prospects for democratic renewal were the subject of a recent conference – Reawakening the Spirit of Democracy – at Johns Hopkins University’s George Peabody Library on democracy around the world

“Fundamentally what we have—and this is what I think is so damaging to democracy—is an increasing problem of trust,” said Washington Post columnist Anne Applebaum, a National Endowment for Democracy board member. “One of the effects of polarization is it makes people distrust mainstream institutions. They think the courts, or the press … have been captured by the other side, so it erodes trust for the institutions that hold the center together.”

“Fundamentally what we have—and this is what I think is so damaging to democracy—is an increasing problem of trust,” said Washington Post columnist Anne Applebaum, a National Endowment for Democracy board member. “One of the effects of polarization is it makes people distrust mainstream institutions. They think the courts, or the press … have been captured by the other side, so it erodes trust for the institutions that hold the center together.”

But democracy can draw on “formidable sources of resilience,” according to a non-partisan group of political scientists.

If a healthy democracy requires “a consensus about which transgressions are critical and which more tolerable, our surveys are a source of optimism,” the watchdog group Bright Line Watch writes in the journal Perspectives on Politics.

The researchers examined whether the public and experts rate the importance of specific democratic principles in the same way, and the extent to which they share similar risk assessments to our basic political institutions, the University of Rochester’s Sandra Knispel writes:

But a robust democracy requires something else. “It also needs broad agreement that leaders have transgressed against one or more important principles of democracy,” the researchers add. “By this measure, our evidence is far less encouraging.”

But a robust democracy requires something else. “It also needs broad agreement that leaders have transgressed against one or more important principles of democracy,” the researchers add. “By this measure, our evidence is far less encouraging.”

While many may wonder if the nation’s democracy is in peril, the group cautions against any such sweeping conclusion. Instead, they argue, “it’s too early to know if the long-term quality of US democracy will suffer. Our political system and civil society retain formidable sources of resilience such as wealth and democratic longevity.”

The next democratic revolution – one that empowers future generations– may well be on the political horizon, claims Roman Krznaric, a public philosopher. It’s common to claim that today’s short-termism is simply a product of social media and other digital technologies that have ratcheted up the pace of political life. But the fixation on the now has far deeper roots, he argues:

- One problem is the electoral cycle, an inherent design flaw of democratic systems that produces short political time horizons. Politicians might offer enticing tax breaks to woo voters at the next electoral contest, while ignoring long-term issues out of which they can make little immediate political capital, such as dealing with ecological breakdown, pension reform or investing in early childhood education. Back in the 1970s, this form of myopic policy-making was dubbed the “political business cycle”.

- Add to this the ability of special interest groups – especially corporations – to use the political system to secure near-term benefits for themselves while passing the longer-term costs onto the rest of society. Whether through the funding of electoral campaigns or big-budget lobbying, the corporate hacking of politics is a global phenomenon that pushes long-term policy making off the agenda.

- The third and deepest cause of political presentism is that representative democracy systematically ignores the interests of future people. The citizens of tomorrow are granted no rights, nor – in the vast majority of countries – are there any bodies to represent their concerns or potential views on decisions today that will undoubtedly affect their lives.