President Bouteflika’s resignation has left Algeria facing a period of uncertainty replete with hope and fear, The (London) Times reports. The hope is that, at long last, this oil and gas-rich nation will witness a transition to democracy and to a market economy that will lead to a prosperous, peaceful future; the fear that it will stumble into a chaos that could provide fertile ground for Islamism while propelling migrants across the Mediterranean.

Although credited with helping foster peace after Algeria’s decade-long civil war, Bouteflika has faced criticism for perceived authoritarianism, AFP adds. Former prime minister-turned-rival Ali Benflis said his departure was the “woeful epilogue” to the past two decades and praised the protest movement as “a peaceful people’s revolution”.

Algeria offers another vivid example of what can happen when unaccountable rulers entrench themselves while ignoring their societies’ pressing need for change, the Post observes.

Credit: Carnegie: Dalia Ghanem Yazbeck

A new government must include civil society, Amina Afaf Chaïeb, entrepreneur and member of Ibtykar, tells France24 (above).

But democratic actors fear that covert measures are being taken to maintain the status quo, albeit in a different guise.

“Recent developments and signals sent by the system confirm the continuation of the ‘clan transition’ option,” says a statement issued by a civil society collective of associations and labor unions dubbed, “For a peaceful way out of the crisis,” Middle East Eye reports:

The ‘clan’ that civil society group refers to are the networks of the former Department of Intelligence and Security (DRS) which was disbanded in 2016. They are still represented by their former boss, Lieutenant General Mohamed Mediene – known as General Toufik – who has come to the fore in recent days, in contrast to his usual low profile.

Algerian unions still plan to hold a three-day general strike starting 7 April unless a transitional government is put in place, IndustriALL reports. Organized labor is demanding a transitional government, which includes members of the opposition, in order to prepare for transparent presidential elections.

IndustriALL

Interestingly, ideology did not play a role in the Hirak, helping it maintain its unity, notes Faten Aggad, an Algerian consultant and advisor on international negotiations:

This was unlike the protests in the early-1990s, which called for the establishment of an Islamic state, and preceded the electoral rise of the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS). By contrast, the Hirak focused on the notion of a Second Republic and insisted on rule of law. This republican character had one purpose: avoid creating an institutional vacuum and even risk plunging the country into chaos.

The protest movement is “unique in the way it managed to mobilize throughout the country and in a repeated manner, over a number of weeks,more than 20 million people around the one key objective: ending the rule of one man and his clan but also bringing about a new free, democratic republic!” analyst Nadia Mehdid نادية محديد @NMehdid Tweeted#Algérie.

Is the army now willing to turn the country’s future entirely over to civilians, with no say? Unlikely, The Times adds:

“They are not going to stop Algerians from searching for a new Algeria, but they want to be present — an actor — because they have interests to protect,” said Hasni Abidi, Algerian-Swiss director of the Center for Study and Research on the Arab and Mediterranean World, in Geneva.

“It this role that is problematic,” Mr. Abidi said. “The army is the only decisive actor. But since Feb. 22” — the date of the first demonstration — “there is another actor: the street.” He added: “It is the army that is saying to the street: ‘I am your interlocutor.’”

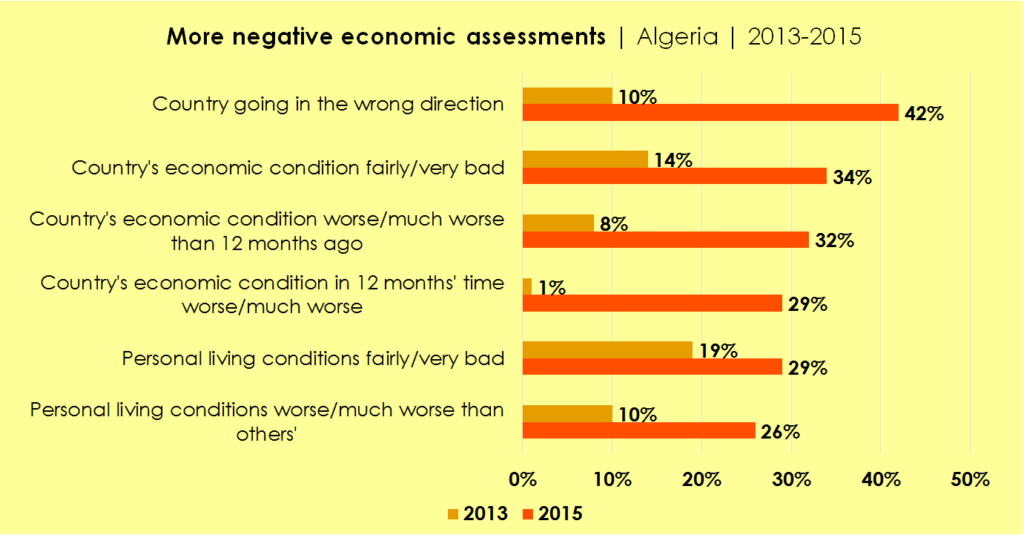

Falling global oil and gas prices have resulted in widespread unemployment, especially among youth, the Post adds.

“Against this backdrop, a bungled leadership transition and continuing economic stagnation could lead to further instability in Algeria that would have significant ramifications for U.S. counterterrorism interests and regional stability,” risk analyst Geoff Porter wrote in a Council on Foreign Relations analysis.

Prolonged unrest in Algeria could provide jihadists additional operational space, enabling them to regroup and rebound, as has occurred in Libya, Egypt and Tunisia, according to Scott Stewart, a security analyst with Stratfor.

“In the absence of a rapid and nonviolent resolution, the unrest is likely to spawn profound security challenges — not only in terms of disruptions and security crackdowns, but also by providing additional space for Algeria’s militant groups to recover and expand.”

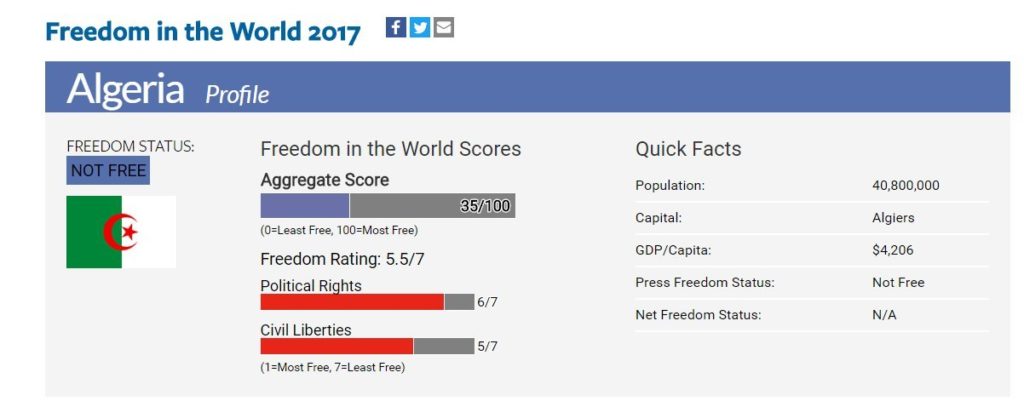

Freedom House deems the Algerian regime to be unfree.

Other observers wonder whether a leaderless movement is able to make the transition from protest to politics that eluded civil society counterparts during the “Arab Spring.”

“If these crowds remain large, if the protesters get more frustrated, if there aren’t much larger concessions, there is a significant risk of violence in Algeria which, of course, has regional repercussions,” said William Lawrence, a political science professor and North Africa expert at George Washington University.

“There is a certain naivete among the protesters, a lack of understanding of Algerian history and politics,” Lawrence said. “Nobody has stepped up, either promoted by the regime or by the protest crowds, that can grab the reins of the ship of state and navigate the ship,” he told The Post:

So far, no one has emerged as a clear successor to Bouteflika. The protesters do not have a clear leader or a clear plan for what they seek….“Le pouvoir” remains in place. The army, now more powerful than ever, hovers in the background.

“There was no party or organisation who made these people come out, it was the young on social networks”, said one observer. ”This is a peaceful revolution of our young and no one has the right to frame it or to try to speak on its behalf… The young should organise themselves. This is a movement that will eventually produce a leadership for the future of this country.”

Mouwatana Facebook page

Even though the movement is leaderless, it is organized—primarily through social media, writes Dalia Ghanem Yazbeck, an Algerian who is a North Africa analyst at the Carnegie Middle East Center. Calls for writing songs, slogans, and signs, and managing the security have circulated on social media, especially on Facebook. This is how one local committee of volunteers was created to protect people and to detect the baltagiya, paid henchmen of the Algerian government.

“The military is ruling the country from the tip of a pyramid of power,” said Ghanem Yazbeck. “Even if there is a new leadership, we may wait a long, long time until this pyramid of power disappears entirely.”

But the situation of the so-called democratic, secular parties is in some respects worse than that of their Islamist counterparts, analyst Nourredine Bessadi writes for the Algiers Herald.

According to an Afrobarometer 2015 survey [i], 78% of Algerians say religion is “very important” in their lives. A 2017 Arab Barometer poll [ii] shows that while most Algerians (64 percent) believe that law should rest partly on sharia and partly on the will of the people, 29 percent believe law should rest entirely on sharia, and 53 percent prefer a religious political party to a secular alternative. Some 64 percent disagree or strongly disagree with the separation of religious practice and socio-economic life.

ECFR Senior Policy Fellow Anthony Dworkin’s research trip to Algiers sheds light on protestors’ visions for political reform in Algeria’s protests: A view from the ground.

The way forward is not yet clear, but not due to the lack of proposals, analyst Aggad writes for African Arguments:

- The first is that the transition stays squarely within the constitutional framework. This would mean the current president of Council of the Nation (upper house of the parliament) taking over and elections being held within 135 days. This option has been widely rejected, however, as it is seen as a way for the establishment to keep hold of power.

- The second option therefore is to operate outside of the limits of the current constitution. This would involve establishing a constituent assembly backed by the population and composed of independent trusted figures.

Which option prevails depends on several factors, Aggad suggests:

- First is the role of the army. As it now stands, the army does not seem to have the appetite to manage the process and repeat the scenario Algeria found itself in in the early 1990s. Furthermore, calls for it to return to the barracks indicates that while opinion was divided on whether the army should take a stand in the protests, there is consensus that it should play no role in the transition.

- The Constitutional Council, whose president is seen to be very close to the Bouteflika clan, will also play an important role. That body will determine the eligibility of the current president of the Council of the Nation, whose nationality has been questioned, to be interim president. The constitution is clear that the president of the republic (elected or otherwise) should not hold dual citizenship.

- Finally, the shape of the transition period depends on how the Hirak organises. Until now, the movement was intentionally left decentralised to avoid it being undermined through attacks on its leaders, either by the government discrediting or arresting them. But the time now is ripe to move to Phase II.

Arab societies are once again depressed and frustrated, the Post adds. Leslie Campbell, a veteran program officer for the National Democratic Institute – a core partner of the National Endowment for Democracy – summed up the regional climate in a recent essay: “Anger over the arrogance and impunity of political, military and economic elites and over persistent governance failures, exacerbated by audacious corruption and extravagant state spending, are reminiscent of the restive mood in 2010 and early 2011.”