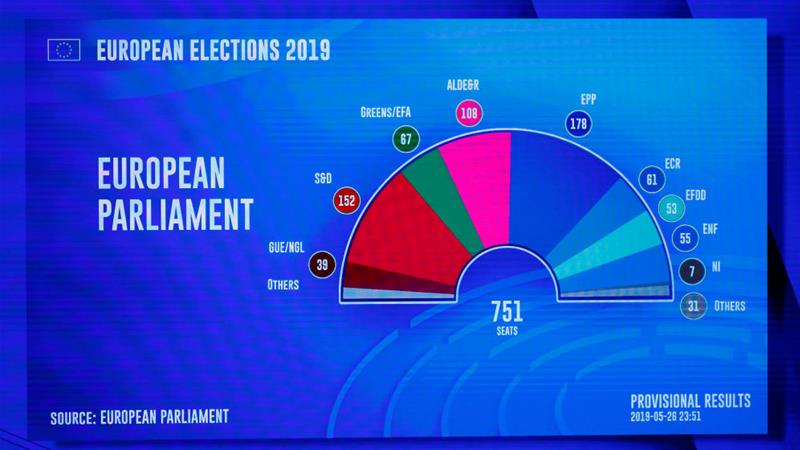

Populists have won nearly three in 10 seats in the European parliament, according to new analysis, which also shows how anti-establishment parties fell short of apocalyptic predictions, The Guardian reports:

Analysis shared with the Guardian reveals that populists, spanning the far right to the radical left, won 29% of seats in European elections, their best ever score, but not the populist wave some had predicted would upend the EU. Matthijs Rooduijn, a political sociologist at the University of Amsterdam, said populists had won 218 of the parliament’s 751 seats. All kinds of populism were on the rise: left, right, as well as groups such as the Brexit party, which cannot be easily categorised. While populists could continue to grow, their fortunes could also change quickly.

“Mainstream parties in general are still struggling to deal with populism,” Rooduijn said. “In the beginning they tried to ignore them, then they have tried to compete with their rhetoric [and] many mainstream right parties have moved towards the radical right; they have not become radical right, but they have become more strict on immigration, more sceptic on European integration.”

The election results indicate that political actors are anachronistic, failing to reflect underlying socio-economic, cultural and ideological shifts, observers suggest.

“It seems that political parties built around the class and economic structures of the 19th and 20th centuries are losing their relevance,” argues FT analyst Gideon Rachman. “European voters are increasingly motivated by new issues — such as climate change, identity and migration. The consequence is likely to be a period of political uncertainty and flux that will make it harder for the EU to act.”

The divisive language against the European Union as the root of all the Continent’s ills “actually galvanized people,” said Nathalie Tocci, the director of Italy’s Institute of International Affairs and a senior adviser to Europe’s foreign policy chief. “All of a sudden Europe means something.” As a result of the large turnout, and a rejuvenation of the European political space by new Green voters and liberals, “the nationalists did not do as well as many feared,” she told The NY Times.

The analysis that populism was contained is wrong because it externalises “populism” to parties that are part of the nontraditional political groups in Brussels, most notably the three rightwing Eurosceptic groups, argues Cas Mudde, author of Populism: A Very Short Introduction. But there are more subtle changes within the various groups, which show a partly different story, he writes for The Guardian:

- First, the new rightwing populist group, the European Alliance of Peoples and Nations will not only be (much) bigger than its predecessor, the Europe of Nations and Freedom (ENF), it will also have a new biggest party. Since 1989 the Front National (now called National Rally) has dominated the European populist radical right, accounting for almost half of the ENF seats in the previous legislature. But Salvini’s League is bigger than Marine Le Pen’s party….

Second, populist parties, as well as parties that pander to nativist and populist audiences, increased their representation, and therefore power, within the various “mainstream” groups. Poland’s Law and Justice party (PiS) became the biggest political party within the “conservative” Eurosceptic European Conservatives and Reformists group, accounting for almost half of all MEPs. It has traditionally been dominated by the British Conservative party. …

Second, populist parties, as well as parties that pander to nativist and populist audiences, increased their representation, and therefore power, within the various “mainstream” groups. Poland’s Law and Justice party (PiS) became the biggest political party within the “conservative” Eurosceptic European Conservatives and Reformists group, accounting for almost half of all MEPs. It has traditionally been dominated by the British Conservative party. …- Third, the two traditional big groups, the European People’s party and the centre-left Socialists & Democrats, lost their majority in the parliament, and will need to depend on (shifting?) coalitions with the liberals and greens. But the old and new centrist groups do not differ only ideologically, but also geographically. Power rests solidly within the west among the liberals and greens, but much less so in the European People’s party and the centre-left Socialists & Democrats. This could be highly problematic when it comes to sociocultural issues, as the vastly different responses between east and west towards the so-called refugee crisis of 2015 demonstrated.

- Fourth, while the increased turnout is indeed good news, with barely half of the population voting in the 2019 European elections, democracy is hardly the big winner. And the argument that the increased turnout was because of the importance of the EU or the prominence of European issues is wishful thinking, given that the biggest increases in turnout were in countries with particularly polarised national politics (such as Austria, Hungary and Romania).

“There was no breakthrough of the populist, right-wing, anti-immigration forces,” said Peter Kreko, executive director of Political Capital, a Budapest research and consulting firm [a partner of the National Endowment for Democracy]. “The big dreams of a huge euroskeptic group seem to have been rather idealistic,” he told AP.

“There are now issues, such as ecology and immigration, that command pan-European interest and require pan-European solutions—and Europeans seem to know it,” NED board member Anne Applebaum writes for the Washington Post.

“There are now issues, such as ecology and immigration, that command pan-European interest and require pan-European solutions—and Europeans seem to know it,” NED board member Anne Applebaum writes for the Washington Post.

Even if the populists succeed in uniting on some decisions, they still have too few seats in the European Parliament to make a profound impact, despite their strong showing, TIME adds. “There are a bit more than 200 members among the nationalists and populists, all put together,” says Fabrice Pothier, Chief Strategy Officer of political consultancy Rasmussen Global, who is French and a strong Macron supporter. “It is not a blocking majority.”

“A political shift is undoubtedly under way. But the real story was the evidence of a new pluralism emerging in EU politics,” analyst Natalie Nougayrede writes for the Guardian.

The current threat posed by political populism to liberal democracy is compounded by three factors, argues Prof. Yuval Shany, vice president for research of the Israel Democracy Institute and a fellow of its Center for Democratic Values and Institutions:

The current threat posed by political populism to liberal democracy is compounded by three factors, argues Prof. Yuval Shany, vice president for research of the Israel Democracy Institute and a fellow of its Center for Democratic Values and Institutions:

- First, political populism has been successful in harnessing identity politics towards its goal of eroding the power of opposing political bodies, by juxtaposing the ‘authentic people’ against migrants, minorities, “condescending elites” and progressive civil society groups, which allegedly promote cosmopolitan values and serve foreign agendas. In this context, some courts have been branded, as ‘enemies of the people’, certain NGOs – as the long arm of George Soros, and a constitutional text defined the State as belonging only to one dominant ethnic group.

- Second, politics in an age of populism is more and more about expressing popular sentiments, and less and less about doing the right thing for the country. Gone are the days of Ben Gurion’s, “I don’t know what the people want, but I know what the people need”, and with them – the ability of politics to deliver sustainable long-term solutions to complex structural problems (such as immigration, or the situation in Gaza). Democracy’s failure to deliver solutions further exacerbates the distrust in it as a system of governance, paving the way for more autocratic alternatives.

- Finally, in a world far removed in time from the pre-1945 historical experience, and flooded with simplistic and demagogic digital messages, it is becoming more and more difficult to explain the nuanced and long-term benefits of key norms and institutions of liberal democracy to the masses. The effectiveness of the populist rhetoric, linking together the future of liberal democracy and the future of a resented political elite (be it the “Washington Beltway” or “judges from Rehavia”) is fast eroding support for key elements of the liberal democracy project.

For liberal democracy to prevail, new political strategies need to be developed, he writes for The Jerusalem Post:

For liberal democracy to prevail, new political strategies need to be developed, he writes for The Jerusalem Post:

Broad and inclusive alliances must be formed in order to present a viable political alternative to exclusive ethnic or religion-based definitions of ‘we the people;’ universal values must be defended and embedded into local culture and belief systems, and significant efforts should be invested in promoting effective education, and political re-affirmation and widespread dissemination of the shared values underlying liberal democracy.

The historical record since 1945 gives us a picture of how populists operate once they hold political power. The record shows that populism is inimical to liberal democracy, and not a corrective to some of its failings, Takis S. Pappas – author of Populism and Liberal Democracy – writes for the Journal of Democracy.

A lazy view of European politics sees the “new” member states in Eastern Europe as proxies for populism, backwardness and corruption, notes Dalibor Rohac, a research fellow at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington DC. Yet, this binary view obfuscates the fact that both old and new member states are facing the same challenges. What is more, it is increasingly the ongoing political ferment in some countries in Eastern Europe that carries in it the promise of revitalizing the European project, he writes for POLITICO.

Robin Niblett, director at Chatham House, looks at European election results and the rise of populism (above).