Veterans of Iran’s reformist movement – Mohsen Aminzadeh, Mohammadreza Khatami, Abdollah Ramezanzadeh, and Mostafa Tajzadeh – are concerned about the “mortal blow that even a limited military conflict with the United States of America will deal to the democratic movement.”

Veterans of Iran’s reformist movement – Mohsen Aminzadeh, Mohammadreza Khatami, Abdollah Ramezanzadeh, and Mostafa Tajzadeh – are concerned about the “mortal blow that even a limited military conflict with the United States of America will deal to the democratic movement.”

“We can already feel the restrictions that the crisis of the last two years has imposed on the fragile civil society and peaceful political activity in Iran,” they write for The New York Review of Books. But Iran’s reformist movement died 20 years ago this week with the suppression of the 1999 protests at Tehran University, observers suggest.

President Mohammad Khatami’s failure to protect the students is one reason that so many Iranian activists who believed for years in the prospect of incremental reform now feel that radical change the only path forward, notes Bloomberg’s Eli Lake:

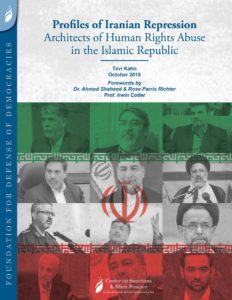

Roya Boroumand, the executive director of the nonprofit Abdorrahman Boroumand Center (right),* told me that the 1999 protests were a lesson for many Iranians who learned that even if reformist politicians supported changes to the law, those changes would be stymied by the unelected clerics who control Iran’s courts and powerful Guardian Council.

Roya Boroumand, the executive director of the nonprofit Abdorrahman Boroumand Center (right),* told me that the 1999 protests were a lesson for many Iranians who learned that even if reformist politicians supported changes to the law, those changes would be stymied by the unelected clerics who control Iran’s courts and powerful Guardian Council.

Following this violent backlash, however, the Islamist leadership somewhat relaxed its repression of dissent, paving the way for more moderate forms of opposition to emerge, Dartmouth College professor Misagh Parsa, the author of Democracy in Iran: Why It Failed and How It Might Succeed, told Middle East Eye.

“Once fully in control, Ayatollah Hashemi Rafsanjani and Ayatollah Ali Khamenei decided to move the Islamic Republic in a new direction and steer away from the radicalism of the first decade,” Parsa said, referring to the leftist-Islamist movement that would later be known as reformism.

“Once fully in control, Ayatollah Hashemi Rafsanjani and Ayatollah Ali Khamenei decided to move the Islamic Republic in a new direction and steer away from the radicalism of the first decade,” Parsa said, referring to the leftist-Islamist movement that would later be known as reformism.

“The ‘radical’ faction reorganised and entered the [1997] presidential elections as the new reformists, who were primarily concerned with democratic rights, civil liberties and the rule of law,” Parsa added. “Students also pressed for similar issues and demanded fair elections during the 1997 presidential elections.”

Washington’s efforts to isolate the Islamic Republic have undermined President Hassan Rouhani’s own push to curb the Guard’s power inside Iran, The – Wall Street Journall adds (HT:FDD). Since taking office in 2013, Mr. Rouhani’s administration encouraged foreign and domestic investors to expand in the transport and oil industry, where the Guard has stakes. But when the U.S. pulled out of the nuclear deal and reimposed sanctions, foreign investors left and Iran’s private sector suffered, leaving an opening for the Guard to expand its economic footprint.

MEMRI

The Iranian regime’s provocative actions are not designed to start a war, says a leading analyst. More likely, it’s to enter talks with Washington claiming to be the empowered party that has withstood America’s strategy of maximum pressure. Before negotiating with the United States, Iran needs a narrative of success, argues Ray Takeyh of the Council on Foreign Relations.

Tensions can also be attributed to the “anti-American sentiment integral to the ideology of the Islamic Republic of Iran ,” argues Columbia University’s Kian Tajbakhsh. The regime’s ideological fixation is the principal obstacle to constructive engagement, analysts suggest.

“You can’t overcome some aspects of the revolutionary ideology still in Iran today,” said Brookings’ Iran analyst Suzanne Maloney.

While credible reports indicate that elements of the establishment in Tehran would welcome a departure of policy that supports non-state actors in the region and a normalization of conventional diplomatic relations, the expectation that it could translate into an actual shift in policy is a case of wishful thinking, adds Hassan Mneimneh, a principal at Middle East Alternatives in Washington. A more plausible assessment would consider the floating of this type of policy realignment a deliberate attempt by those with real power in the regime to encourage international calls for a ‘soft approach’ to dilute the resolve of their regional and international opponents, he writes for WINEP’s Fikra Forum.

While credible reports indicate that elements of the establishment in Tehran would welcome a departure of policy that supports non-state actors in the region and a normalization of conventional diplomatic relations, the expectation that it could translate into an actual shift in policy is a case of wishful thinking, adds Hassan Mneimneh, a principal at Middle East Alternatives in Washington. A more plausible assessment would consider the floating of this type of policy realignment a deliberate attempt by those with real power in the regime to encourage international calls for a ‘soft approach’ to dilute the resolve of their regional and international opponents, he writes for WINEP’s Fikra Forum.

In the wake of considerable domestic unrest in 2018 and sporadic unrest this year, we should not be surprised to see leadership changes across Iran’s security agencies — especially the Basij – the Organization for the Mobilization of the Oppressed (Sazeman-e Basij-e Mostazafan), notes Saeid Golkar, an assistant professor at the Department of Political Science at the University of Tennessee, Chattanooga and a senior fellow on Iran policy at the Chicago Council on Global Affairs. The shift in leadership – Brig. Gen. Gholam Hossein Gheibparvar was replaced by Brig. Gen. Gholamreza Soleimani – indicates how the regime’s threat perceptions are changing — especially regarding Iran’s concern over a new wave of mass unrest, he writes for War On The Rocks.

Since its inception, the Basij – one of the most effective forces in the clerical regime’s tool kit for combating domestic unrest – has created more than 21 different branches for recruiting and organizing Iranians among different social strata and professions, including the Workers Basij Organization, Employees Basij Organization, and Engineers Basij Organization. With the recent change, the Basij adopted a double identity: a civilian identity and a military identity as a force under the direct control of the Guard Corps, Golkar adds.

Since its inception, the Basij – one of the most effective forces in the clerical regime’s tool kit for combating domestic unrest – has created more than 21 different branches for recruiting and organizing Iranians among different social strata and professions, including the Workers Basij Organization, Employees Basij Organization, and Engineers Basij Organization. With the recent change, the Basij adopted a double identity: a civilian identity and a military identity as a force under the direct control of the Guard Corps, Golkar adds.

Iran is instrumentalizing non-state actors beyond its borders too.

On Monday, Iraqi Prime Minister Adel Abdul Mahdi issued a decree heavily curbing the powers of majority Iran-backed Shi’ite militia groups, forcing them to integrate further into the country’s formal armed forces, Iraqi civil society groups report.

The Basij is used by the regime to suppress dissidents, vote as a bloc, and indoctrinate Iranian citizens, Golkar notes in his book, Captive Society: The Basij Militia and Social Control in Iran (above):

To improve the Basij’s engagement in scientific, cultural, defensive, and public service arenas, Gheibparvar implemented the “Basij Transcendence Plan,” a series of programs to enact Khamenei’s vision. Through these policies, he attempted to recast the Basij as a force for social services, so younger Iranians would be more drawn to join. This new plan consisted of five main projects: educational, security, cultural, developmental, and health. For example, the Basij shaped more than 11,000 small groups to be deployed in poor and undeveloped areas for developmental projects. The Basij also deployed medical practitioners to similar neighborhoods and rural areas to visit impoverished people and provide them with medication.

To improve the Basij’s engagement in scientific, cultural, defensive, and public service arenas, Gheibparvar implemented the “Basij Transcendence Plan,” a series of programs to enact Khamenei’s vision. Through these policies, he attempted to recast the Basij as a force for social services, so younger Iranians would be more drawn to join. This new plan consisted of five main projects: educational, security, cultural, developmental, and health. For example, the Basij shaped more than 11,000 small groups to be deployed in poor and undeveloped areas for developmental projects. The Basij also deployed medical practitioners to similar neighborhoods and rural areas to visit impoverished people and provide them with medication.

The new leader, Soleimani, is strengthening of the Basij’s security and defense missions, which are seen to have been weakened since 2009, and working in close alignment with the supreme leader and the new commander of the Guard Corps. This development signals a change in the regime’s threat perceptions in response to Iran’s political and socio-economic deterioration. RTWT

*A National Endowment for Democracy grantee.