Forty years have passed since my father was pursued by the KGB for exercising a citizen’s simple right to read, to listen to what they chose and to say what they wanted, notes Peter Pomerantsev, author of This Is Not Propaganda: Adventures in the War Against Reality.

Forty years have passed since my father was pursued by the KGB for exercising a citizen’s simple right to read, to listen to what they chose and to say what they wanted, notes Peter Pomerantsev, author of This Is Not Propaganda: Adventures in the War Against Reality.

Today, the world he hoped for, in which censorship would end – as the Berlin Wall would fall – can seem much closer: we live in what academics call an era of “information abundance”. But the assumptions that underlay the struggles for rights and freedoms in the 20th century – between citizens armed with truth and information and regimes with their censors and secret police – have been turned upside down. We now have more information than ever before, but it hasn’t only brought the benefits we expected, he writes for The Guardian:

Information was the front line in the battle of democracy and dictatorship in the 20th century, the space where victory was articulated and supposedly secured. Since then it has become the arena where democracy is undermined. But it can also be the place where big words such as “rights” and “freedoms”, words that have been appropriated by a new generation of manipulators and oppressive regimes, are given meaning again.

Pomerantsev offers compelling fine detail of the ways in which social media campaigns would stoke fears about threats to a national way of life and offer simplistic solutions, The Observer’s Tim Adams notes. These campaigns, automated and relentless, as well as cynical and blunt, were never designed to change thinking through argument but rather to change the environment in which arguments are made.

“It is not the case that one online account changes someone’s mind,” Pomerantsev notes. “It is that en masse they create an ersatz normality.”

Computer technology appears to be delivering heightened anxiety or rage; surveillance regimes that are the first in history to deserve the term Orwellian; and a sense that the mechanisms of democracy are about as robust as a sand castle facing a spring tide. It is this final critical issue, the relationship between information technology and political culture, that Pomerantsev addresses, Misha Glenny adds in The [London] Times.

Computer technology appears to be delivering heightened anxiety or rage; surveillance regimes that are the first in history to deserve the term Orwellian; and a sense that the mechanisms of democracy are about as robust as a sand castle facing a spring tide. It is this final critical issue, the relationship between information technology and political culture, that Pomerantsev addresses, Misha Glenny adds in The [London] Times.

What we are seeing is, in the words of Columbia law professor Tim Wu, a situation where “speech itself is seen as a censorial weapon”, Pomerantsev adds. This questions the old idea that the answer to “fallacious speech” is “more speech” – that we live in a “marketplace of ideas” where the best “information products” will win out. What if that market can be rigged?

Washington Post Senior Tech Policy Reporter Tony Romm joined Yasmin Vossoughian to discuss how Iran and other countries are actively using Russia’s disinformation tactics, while David Salvo, Deputy Director for the Alliance for Securing Democracy, discussed solutions for fixing election vulnerabilities.

Researchers for FireEye and other firms have reported suspected Iranian disinformation on most major social media platforms — Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, Google+ and others — and on stand-alone websites, as well. In May, FireEye also alleged that U.S. news sites may have been tricked into publishing letters to the editor penned by Iranian operatives, The Washington Post reports.

Researchers for FireEye and other firms have reported suspected Iranian disinformation on most major social media platforms — Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, Google+ and others — and on stand-alone websites, as well. In May, FireEye also alleged that U.S. news sites may have been tricked into publishing letters to the editor penned by Iranian operatives, The Washington Post reports.

“Multiple foreign actors have demonstrated an ability and willingness to leverage these kinds of influence operations in pursuit of their geopolitical goals,” said Lee Foster, head of the intelligence team investigating information operations for FireEye, a cybersecurity firm based in California. “We risk the U.S. information space becoming a free-for-all for foreign interference if, as a society, we fail to get an effective grasp on this problem.”

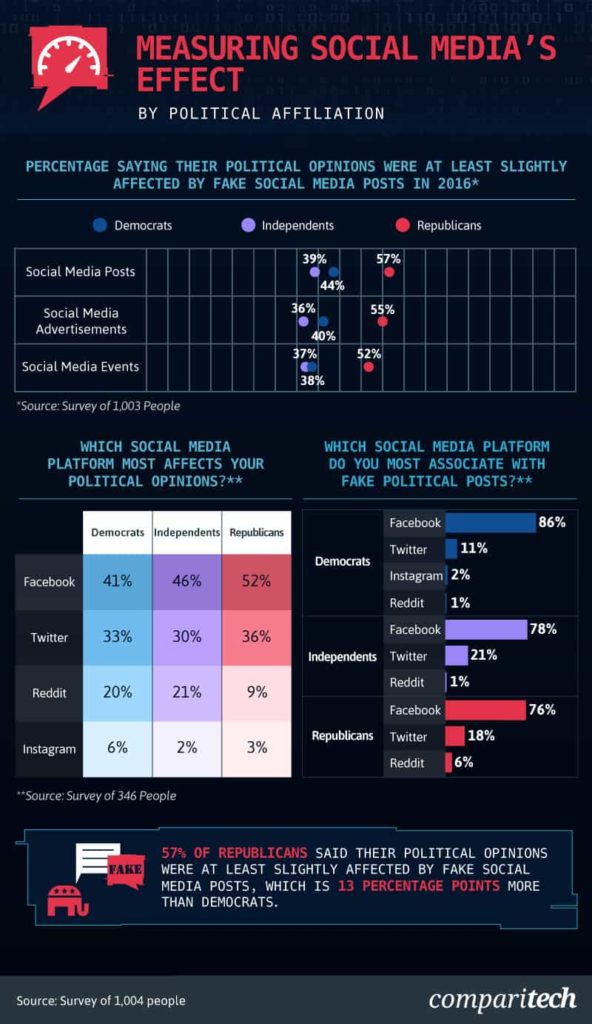

Facebook is more associated with fake political posts than any other social network. It is also the social network that most affects our opinions, according to a Comparitech survey of over 1,000 people (see below).

Facebook is more associated with fake political posts than any other social network. It is also the social network that most affects our opinions, according to a Comparitech survey of over 1,000 people (see below).

Social media was among the top two concerns for all three political affiliations, the survey found. A large majority across all parties did not think social media companies did enough to curb the spread of fake political posts. Eighty-seven and 86 percent of Democrats and Independents, respectively, thought social media companies could step it up, but 35 percent of Republicans thought they did enough.

Trials and tribulations of fighting disinformation

This week, the Russian Prosecutor General unexpectedly announced his decision to add the Atlantic Council to its list of “undesirable organizations,” which include the National Endowment for Democracy. But the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab) will continue its mission “to identify, expose, and explain disinformation when and wherever it occurs using open, verifiable evidence available to all,” it said.

This week, the Russian Prosecutor General unexpectedly announced his decision to add the Atlantic Council to its list of “undesirable organizations,” which include the National Endowment for Democracy. But the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab) will continue its mission “to identify, expose, and explain disinformation when and wherever it occurs using open, verifiable evidence available to all,” it said.

Can we inoculate ourselves against disinformation, just like we would against measles? Coda Story’s Isobel Cockrell asks. It’s a thought preoccupying me this week after reading this Reddit thread between thousands of redditors and a professor at DROG, a Dutch anti-disinfo think tank. DROG has set out to “vaccinate” people against disinformation campaigns and increase skepticism of fake news by exposing the methods behind them by using interactive games.

Can we inoculate ourselves against disinformation, just like we would against measles? Coda Story’s Isobel Cockrell asks. It’s a thought preoccupying me this week after reading this Reddit thread between thousands of redditors and a professor at DROG, a Dutch anti-disinfo think tank. DROG has set out to “vaccinate” people against disinformation campaigns and increase skepticism of fake news by exposing the methods behind them by using interactive games.