POMED

Tunisia’s election commission has approved (HT: FP) a list of candidates for the country’s presidential vote. There are 26 candidates, among them the current prime minister and defense minister, a former president, and a media mogul. Tunisia’s next leader will be the second democratically-elected president since the 2011 Arab Spring uprising.

Among candidates approved for the presidential race are Prime Minister Youssef Chahed, former premier Mehdi Jomaa, the vice-president of the moderate Islamist party Ennahda, Abdel Fattah Mourou, and Defence Minister Abdelkarim Zbidi. Former Tunisian president Moncef Marzouki and Nabil Karoui, businessman and owner of the private channel Nessma TV, will also join the race, AFP adds.

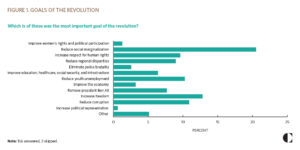

A fragile peace prevails, despite ideological, political and social differences, but the consensus could not break down at any moment, notes Lina Ben Mhenni, an assistant lecturer at Tunis University and the award-winning blogger behind A Tunisian Girl, which has followed the progress of the revolution since 2010.While much has been done in terms of collective and individual freedoms, and launching initiatives to benefit civil society, corruption, smuggling, unemployment and a failing economy remain key issues, as well as much-needed reforms of the education and health sectors, she writes.

Tunisian analyst Mohamed-Dhia Hammami described the Islamist party’s decision to nominate Mourou as “clever” because his “popularity goes beyond the traditional base of Ennahda,” setting up a likely runoff between Mourou and populist candidate Nabil Karoui, adds the Project for Middle East Democracy, a National Endowment for Democracy partner.

Tunisian analyst Mohamed-Dhia Hammami described the Islamist party’s decision to nominate Mourou as “clever” because his “popularity goes beyond the traditional base of Ennahda,” setting up a likely runoff between Mourou and populist candidate Nabil Karoui, adds the Project for Middle East Democracy, a National Endowment for Democracy partner.

The first post-Essebsi elections could cause further fragmentation for Tunisia’s fragile democracy, analyst Alessandra Bajec writes for @The_NewArab:

“With Morou running for president and Ghannouchi for parliament, Ennahdha has significant chance to take the control of the executive & legislative branches of the government. It will be difficult for them to get a majority, but they may end up in a strategically strong position,” Tunisian analyst Hammami tweeted days ago… There will not be a political crisis as all the different parties and aspirants are working toward a very tight electoral schedule, and have no time to lose.

“The political sphere is very fragmented, power is divided, and everyone is focusing on the elections,” he said,

Widely hailed as the only successful political transition to emerge from the Arab Spring, analysts like Safwan Masri have gone so far as to describe Tunisia as an Arab anomaly (left).

Widely hailed as the only successful political transition to emerge from the Arab Spring, analysts like Safwan Masri have gone so far as to describe Tunisia as an Arab anomaly (left).

The culmination of this transition was the election of Mohamed Beji Caid Essebsi in 2014. Essebsi’s victory would make history. He became the first president to be elected in a free and fair election in the nation’s history, note the University of Central Florida’s

Following Essebsi’s death in July this year, politics has played out as observers had expected. His constitutional successor, Mohamed Ennaceur, has taken power on an interim basis. The presidential election has been brought forward to September 15 when the survival of Tunisia’s democratic experiment, and particularly the reforms began by President Essebsi, will be determined by voters, they write for The Conversation:

Voters have shown little faith in the current political parties, and there is a growing disenchantment with democracy. Thus, the election in September will no doubt be a test for Tunisia’s young democracy. While the risk of military intervention and broader instability in the run-up to the poll is likely to be extremely low, it will be important to focus on post-election events. It is important that relations between the conservative religious parties and the secularist, progressive parties remain civil.

CARNEGIE

Even then, the rise of populist candidates and the relative decline in support for the mainstream Ennahdha and Nidaa Tounes parties may test the political norms created under Essebsi’s tenure, they suggest.

Experts have expressed concern that electing a new president before voting for parliament could endanger Tunisia’s democracy, saying this could lead to fewer viewpoints being represented in the legislature. This, in turn, could also threaten the legislative branch’s check on the executive, The Jerusalem Post adds.

“Given the power sharing efforts between Islamists and secularists, as demonstrated in recent years by [the moderate religious] Ennahda [Party] and the [secular liberal] Nidaa Tounes Party, such an electoral calendar shift could potentially spark a constitutional crisis, as the legislative election will not serve as a balancing weight,” Arnaud Kurze, a global fellow at the Woodrow Wilson Center, told The Media Line:

According to Carnegie analyst Sarah Yerkes, “Karoui continues to do well in the polls and seems to be attractive because of his charitable work and name recognition.” Mourou is the first candidate put forth by the Ennahda Party since the Arab Spring. He is known for his moderate positions and opposition to the Muslim Brotherhood. “I think Mourou will do very well as Ennahda‘s first ever presidential candidate,” Yerkes contended.

NED

Ennahda’s de facto leader Rached Ghannouchi is facing rising opposition from within his own party from a new generation of leaders, some of whom believe that Ennahda had gained little from its entente with secular allies, notes Daniel Brumberg (left), a non-resident Senior Fellow at the Arab Center and contributor to the NED’s Journal of Democracy:

Facing the prospect that Karoui might secure the presidency and, worse, forge an alliance with secular parties, Ghannouchi has made a move he long eschewed: he has announced his intention to run for parliament, thus opening up the possibility that he might vie for the position of prime minister. This prospect has galvanized political veterans such as Moncef Marzouki who, along with other like-minded allies, is struggling to unite the secular camp behind the drive to defeat Ennahda. Thus, to the evident dismay of many Tunisians—whose primary concern is simply making a living—identity battles now define the very core of the upcoming elections.

These rising electoral stakes have also prompted increased scrutiny of possible foreign funding for Tunisia’s contending parties and leaders, adds Brumberg, Associate Professor and Director of Democracy and Governance Studies at Georgetown University’s Department of Government:

These rising electoral stakes have also prompted increased scrutiny of possible foreign funding for Tunisia’s contending parties and leaders, adds Brumberg, Associate Professor and Director of Democracy and Governance Studies at Georgetown University’s Department of Government:

Ennahda’s leaders are deeply concerned about this issue. Whether there is clear evidence to support their worries or not, they clearly believe that money from the UAE and Saudi Arabia—as well as political (and perhaps financial) support from France—is pouring in, thus giving an unfair advantage to their secular rivals. …. Ennahda’s leaders sense that they are going into an electoral campaign that is stacked against them. These fears are magnifying the existential angst that many leaders are bringing to the electoral arena. Indeed, some secular leaders are as quick to accuse Qatar of trying to buy support in Tunisia as Islamist leaders are keen to warn of UAE or Saudi funding.