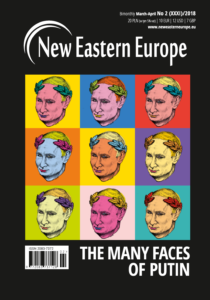

Vladimir Putin has now been in power in Russia as president and prime minister for twenty years. The local elections held in September provide an opportunity to evaluate the results of his rule, says a leading expert.

Vladimir Putin has now been in power in Russia as president and prime minister for twenty years. The local elections held in September provide an opportunity to evaluate the results of his rule, says a leading expert.

Winston Churchill said that Stalin inherited a country with a wooden plough and left it with a nuclear bomb. If he were alive today, he would say something along the lines of, Putin inherited Russia as a quasi-democracy and will surely leave it as a political desert … with authoritarian institutions and degraded elites and society, notes Nikolai Petrov Senior Research Fellow with the Russia and Eurasia Program at Chatham House.

Given that the foundations of Putin’s earlier ‘super-legitimacy’ have eroded and no longer support the edifice of the regime, the Kremlin could have done one of two things: strengthen the legitimacy of the regime, or reorganize the whole system, he writes for the World Today:

This is the legitimacy trap Putin has created for himself. There is not much he can do to restore his legitimacy: improving the economy will take a long time if it happens at all. Foreign policy is a more promising area for the regime to score quick wins, but ordinary Russians no longer care much about this. Without a new Crimea, the regime needs to transform domestically – either loosening or, conversely, tightening the screws in order to keep in power.

Levada

In a development that could point to a broader sea change in Russian attitudes in a direction that challenges the authorities, a new Levada Center poll conducted in August finds that Russians are less concerned about economic issues than political questions, Paul Goble writes for Window on Eurasia.

Russians told Levada pollsters that they were more concerned about corruption and bribery than a year ago (41 percent as against 33 percent), the impossibility of getting justice in the courts (13 percent against nine percent), the repressive actions of siloviki (11 percent compared to seven percent), and conflicts among the branches of the state (six percent against three percent).

“Perhaps equally important, however, is the fact the percentage of Russia respondents concerned about human rights in general rose only one percent (from six to seven percent) and that the share concerned about ‘the weakness of state power’ jumped from nine percent last year to 15 percent this,” Goble adds.

As for the opposition, the summer protest movement showed that “the opposition’s strength lies in the sometimes irrational moves of the establishment,” notes Mikhail Vinogradov (left), the president of the “St. Petersburg Politics” foundation, one of Russia’s leading think tanks.

As for the opposition, the summer protest movement showed that “the opposition’s strength lies in the sometimes irrational moves of the establishment,” notes Mikhail Vinogradov (left), the president of the “St. Petersburg Politics” foundation, one of Russia’s leading think tanks.

Does this mean that for all the weakness of the opposition, it also has a strength that enables it to have some impact on the political process? analyst Masha Lipman asks in PONARS Eurasia:

Vinogradov: This strength has to do with the fact that the political space in post-Soviet Russia, and, to various extents, also in other periods of the Russian history, has never been conceived as a venue for settling differences among various social, public, ideological groups, various lobbying forces, etc. There is no sense here that this is what politics was invented for in the first place. As a result, the differences and contradictions remain under the surface and this is what endows the opposition with some strength. …

In recent years the establishment has displayed a preference for simplification, so all the complex developments would be explained by just one factor. This scheme is tempting from the point of view of the political tactics, but it fails to manage the risks. And the establishment’s failure to understand that risk-management is an important instrument of the retention of power leads to a social turbulence. The protest movement benefits from the government’s reluctance to understand the complexity of the society. Although this movement is essentially weak and lacks a general strategy, it is fueled by this energy of unresolved and unarticulated contradictions.