Thirty years ago, a wave of optimism swept across Europe as walls and regimes fell, and long-oppressed publics embraced open societies, open markets and a more united Europe. Three decades later, a new Pew Research Center survey finds that few people in the former Eastern Bloc regret the monumental changes of 1989-1991. Yet, neither are they entirely content with their current political or economic circumstances. Indeed, like their Western European counterparts, substantial shares of Central and Eastern European citizens worry about the future on issues like inequality and the functioning of their political systems, say Pew researchers , , , , , AND .

Most Poles, Czechs and Lithuanians, and more than 40% of Hungarians and Slovaks, for example, said they felt most people in their countries were better off than 30 years ago; in Russia, Ukraine and Bulgaria, more than half felt things were worse, the Guardian adds:

Most Poles, Czechs and Lithuanians, and more than 40% of Hungarians and Slovaks, for example, said they felt most people in their countries were better off than 30 years ago; in Russia, Ukraine and Bulgaria, more than half felt things were worse, the Guardian adds:

Asked how they felt their countries had advanced, central and eastern Europeans were most positive about education (65%), living standards (61%) and national pride (58%). They were less happy about about law and order (44%) and family values (41%), and a majority (53%) said healthcare had got worse in the post-communist era.

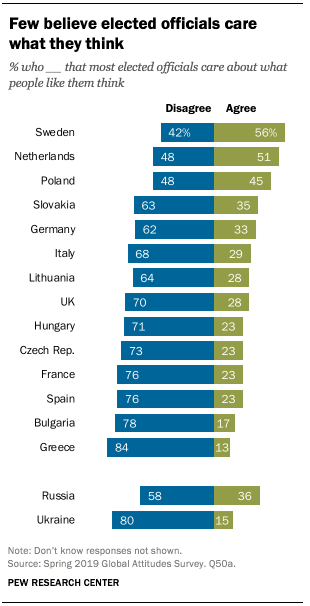

But citizens across all the former communist states were “mostly pessimistic about the functioning of the political system, and about specific economic issues like jobs and inequality”, the survey’s authors said.

The former Eastern bloc and democracy: Key takeaways

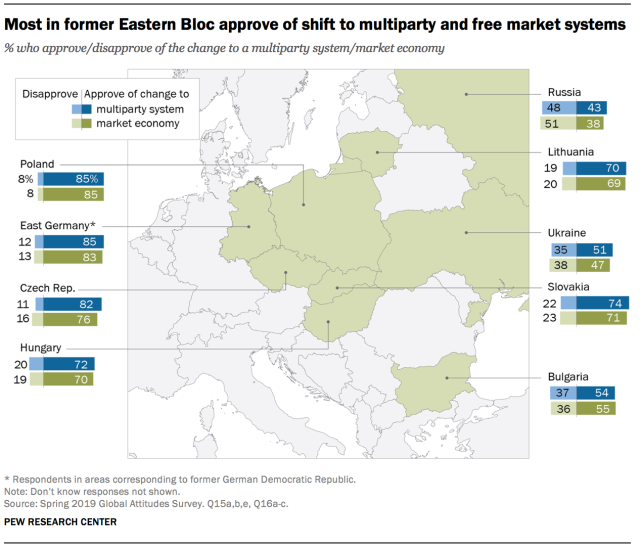

- Poland and the former East Germany had the highest level of support (85%) for the transition to a multiparty democracy.

- The lowest level of support for this transition was found in Bulgaria (54%), Ukraine (51%) and Russia (43%).

- Levels of support for the free market economy generally mirrored those of democracy.

- These levels have not been fixed over time; in comparison to levels measured in 1991 and 2009, support in Hungary, Lithuania and Ukraine has increased.

- When asked to choose among very important democratic priorities, respondents from former East bloc countries most commonly chose a fair judiciary, followed by gender equality and free speech.

- Free civil society and free religion were the least commonly selected answers.

- Large majorities in the former Eastern bloc countries believe that elites gained more from the changes than ordinary people.

For Central Europeans, 2019 marks key anniversaries, including 30 years since the end of communism in the region and 20 years of NATO and 15 years of EU membership. Three decades on, however, Central Europeans are polarized about the outcomes of these historic changes.

Recent reporting on and from the region has been strongly negative. Societies have become fatigued with the post-1989 establishment and populist politicians now dominate political systems. Extremist forces are growing and corruption is flourishing. There is a growing political and cultural divide between ‘Old’ and ‘New’ Europe. Foreign actors are working to exacerbate and capitalize on the region’s democratic backsliding.

Recent reporting on and from the region has been strongly negative. Societies have become fatigued with the post-1989 establishment and populist politicians now dominate political systems. Extremist forces are growing and corruption is flourishing. There is a growing political and cultural divide between ‘Old’ and ‘New’ Europe. Foreign actors are working to exacerbate and capitalize on the region’s democratic backsliding.

At the same time, experts have noted that the region is proving to be more resilient to the global crisis of democracy than expected. New political movements, independent media, and civil society groups are challenging populists. Public protests against extremism and corruption have become the norm across the region. Societies’ support for democratic values, the EU, and NATO remains strong. Foreign malign influence has been less effective than once feared.

As we approach the anniversary of the November 1989 Fall of the Berlin Wall, Daniel Milo and Dominika Hajdu will offer a nuanced assessment of where Central Europe stands today and the challenges it confronts. They will present Globsec Trends 2019: Central & Eastern Europe 30 Years after the Fall of the Iron Curtain. Produced by one of the region’s leading think tanks, the publication is based on the findings and assessment of more than 10,000 interviews conducted in seven countries including Austria, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Slovakia. Iulia Joja and Joanna Rohozinska will join them in a discussion on how the region perceives the fall of communism today, whether Central Europeans feel a part of the West, in what way do citizens view civil society, and what role Russia is playing in the region, among other topics.

As we approach the anniversary of the November 1989 Fall of the Berlin Wall, Daniel Milo and Dominika Hajdu will offer a nuanced assessment of where Central Europe stands today and the challenges it confronts. They will present Globsec Trends 2019: Central & Eastern Europe 30 Years after the Fall of the Iron Curtain. Produced by one of the region’s leading think tanks, the publication is based on the findings and assessment of more than 10,000 interviews conducted in seven countries including Austria, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Slovakia. Iulia Joja and Joanna Rohozinska will join them in a discussion on how the region perceives the fall of communism today, whether Central Europeans feel a part of the West, in what way do citizens view civil society, and what role Russia is playing in the region, among other topics.

The National Endowment for Democracy invites you to a discussion of recent developments in Central Europe featuring a presentation of the GLOBSEC Trends 2019 by

The National Endowment for Democracy invites you to a discussion of recent developments in Central Europe featuring a presentation of the GLOBSEC Trends 2019 by

Daniel Milo, Head of Strategic Communication Program, GLOBSEC Policy Institute

Dominika Hajdu, Research Fellow, GLOBSEC Policy Institute

followed by a conversation with

Iulia Joja, Senior Researcher, Global Focus

Joanna Rohozinska, Senior Program Officer for Europe, National Endowment for Democracy

moderated by

Christopher Walker, Vice President for Studies and Analysis, National Endowment for Democracy

Thursday, October 24. 3:30 p.m.–5:00 p.m. 1025 F Street, N.W., Suite 800, Washington, DC 20004. RSVP

Speaker Biographies

Daniel Milo is Head of the Strategic Communication Program at the GLOBSEC Policy Institute in Slovakia. He holds a JD in criminal law from Comenius University. He previously served as head of a national anti-racist NGO in Slovakia, adviser to OSCE/ODIHR in Warsaw, and coordinator of anti-extremist policies in the Slovak Ministry of the Interior.

Dominika Hajdu is Research Fellow at the GLOBSEC Policy Institute. She holds a MA in European Studies from the University of Leuven. She previously trained with the European Committee of the Regions and worked at the Foreign Policy Department in the Office of the President of the Slovak Republic.

Iulia Joja is Senior Research at Global Focus in Romania and a Transatlantic Fellow at SAIS, Johns Hopkins University. She holds a PhD in Strategic Culture from NSPAS Bucharest and a MA in International Conflict Studies from Kings College. She also teaches at the Bucharest University of Economic Studies.

Joanna Rohozinska is Senior Program Officer for Europe at the National Endowment for Democracy.

Christopher Walker is Vice President for Studies and Analysis at the National Endowment for Democracy.