Enhancing global prosperity must begin with supporting locally-led initiatives that eliminate institutional barriers to freedom—and give citizens greater choice over their future, according to a new book.

Governments and philanthropists spend billions of dollars on foreign-led initiatives that prop up traditional models of international development. But real solutions to poverty emerge from local actors with a vision of change based on a local understanding of sustainable growth, Atlas Network president Matt Warner argues in Poverty & Freedom.

Governments and philanthropists spend billions of dollars on foreign-led initiatives that prop up traditional models of international development. But real solutions to poverty emerge from local actors with a vision of change based on a local understanding of sustainable growth, Atlas Network president Matt Warner argues in Poverty & Freedom.

“In every country there are barriers—unfair laws, corrupt practices, unworkable bureaucracies—that disproportionately harm low-income people,” Warner explains, drawing on thirteen case studies to highlight the work of local think tanks engaged in expanding freedom for vulnerable populations by combating government abuses, making markets more inclusive, and removing additional barriers to opportunity.

The president of Atlas Network, a U.S. based NGO focused on advancing freedom and economic opportunity, Warner coined the phrase “the outsider’s dilemma” to describe the challenge of aiding low-income countries without perversely impeding the most viable paths to prosperity.

“Outsiders have a lot of ideas about how to fix those problems, but the more effective approach is to support local visionaries who better understand what needs to change, how to change it, and how to communicate the benefits of those changes to local stakeholders,” adds Warner, a Penn Kemble Fellow at the National Endowment for Democracy and a recipient of America’s Future Foundation’s Buckley Award.

“Outsiders have a lot of ideas about how to fix those problems, but the more effective approach is to support local visionaries who better understand what needs to change, how to change it, and how to communicate the benefits of those changes to local stakeholders,” adds Warner, a Penn Kemble Fellow at the National Endowment for Democracy and a recipient of America’s Future Foundation’s Buckley Award.

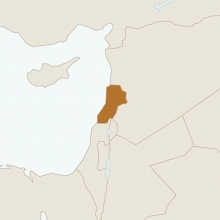

Inequality has prompted major protests from Chile to Iraq and Lebanon in recent weeks.

NDI

In the past week, protests erupted throughout Lebanon against financial measures planned by the government of Saad al-Hariri to address the country’s severe economic crisis. It quickly became evident, however, that the motivation for the protests ran deeper and reflected profound hostility to a political class perceived as corrupt and ineffective, Carnegie nonresident scholar Joseph Bahout told Diwan.

Heather Boushey, the executive director and chief economist at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, a grant-giving organization founded in 2013, has provided a timely and very useful guide to some recent research on the relationship between markets, inequality and democracy.

In her book “Unbound: How Inequality Constricts Our Economy and What We Can Do About It,” Boushey assimilates a great deal of recent economic research and argues that it amounts to a paradigm shift, the New Yorker’s John Cassidy writes:

In her book “Unbound: How Inequality Constricts Our Economy and What We Can Do About It,” Boushey assimilates a great deal of recent economic research and argues that it amounts to a paradigm shift, the New Yorker’s John Cassidy writes:

Referring to Thomas Kuhn’s book “The Structure of Scientific Revolutions,” from 1962, she writes, “Scientific knowledge isn’t accessible as absolute truth: it develops only through the consensus of scholars in a particular field, whose work is upended by scientific discoveries that challenge existing frameworks and forced the paradigm to shift. New data-driven discoveries are causing just such a revolution in economics today.” …Boushey’s main theme is that inequality of various kinds impedes economic development at the individual and aggregate levels: “A rising tide can’t lift all boats when some can’t even get launched and others, pushed off course and deprived of navigation tools, founder on the rocks.”

Drawing on a path analysis of democracy, inequality and corruption perceptions indices Peter Maille of Eastern Oregon University finds that “high inequality democracies are associated with elevated corruption, lower per capita income, and a ceiling on democratic achievement.”

But rather than awaiting a pluralist or democratic awakening, it is probably more productive to try and remake the social order that led to populism’s rise in the first place, Udi Greenberg writes for the Boston Review. The success of this effort will depend on the participation of Christians, who have often been central to struggles for egalitarianism and provide crucial infrastructure for social mobilization. As Carlo Invernizzi Accetti’s What Is Christian Democracy? Politics, Religion and Ideology rightly points out, this means that some ardent secularists may need to overcome ingrained anti-clerical suspicion, he adds, but the project of upending inequalities and securing democracy is far more important than debates over the limits of public funding to religious schools or charities.

But rather than awaiting a pluralist or democratic awakening, it is probably more productive to try and remake the social order that led to populism’s rise in the first place, Udi Greenberg writes for the Boston Review. The success of this effort will depend on the participation of Christians, who have often been central to struggles for egalitarianism and provide crucial infrastructure for social mobilization. As Carlo Invernizzi Accetti’s What Is Christian Democracy? Politics, Religion and Ideology rightly points out, this means that some ardent secularists may need to overcome ingrained anti-clerical suspicion, he adds, but the project of upending inequalities and securing democracy is far more important than debates over the limits of public funding to religious schools or charities.

Increasing inequality is a contributory factor to democratic deterioration, alongside political alienation, xenophobia and polarization, argues Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor. In the first of the annual Walter-Benjamin-Lectures at Berlin’s Humanities and Social Change Center (above), he outlines vulnerabilities and susceptibilities to degeneration inherent to modern democracy as well as possible routes out of crisis.

“Democracies suffer from a potential slide towards disproportionate power of élites, they rely on unifying political identities which can easily slide towards the exclusion of certain citizens as non-members, and they allow for opposing factions to make temporary victories irreversible,” he observes. “In order to flourish or even survive, democracies, far from being automatically self-sustaining, have to address these dangers.”

Citizens who consider income distribution in their country’s to be unfair, tend to be less satisfied with its democratic practices, according to recent research. Perceived unfairness of income inequality provides a better explanation of democratic discontent than the Gini index, a commonly used objective measure of inequality, Taiwan University’s Wen-Chin Wu and Yu-Tzung Chang write in the latest issue of Democratization, using data collected through the fourth-wave Asian Barometer Survey and the Latinobarómetro Survey in 28 East Asian and Latin American democracies during 2013 and 2016.

Citizens who consider income distribution in their country’s to be unfair, tend to be less satisfied with its democratic practices, according to recent research. Perceived unfairness of income inequality provides a better explanation of democratic discontent than the Gini index, a commonly used objective measure of inequality, Taiwan University’s Wen-Chin Wu and Yu-Tzung Chang write in the latest issue of Democratization, using data collected through the fourth-wave Asian Barometer Survey and the Latinobarómetro Survey in 28 East Asian and Latin American democracies during 2013 and 2016.

Prospects for democratic renewal require accepting the limitations of markets – as detailed in Raghuram Rajan’s The Third Pillar and Binyamin Appelbaum’s The Economists’ Hour – a growing concern to economists and policy-makers alike.

“Supply-side economics spawned supply-side politics – the capture of politics by those

who benefit from the status quo,” according to a recent Brookings paper by Isabel V. Sawhill. “The ability of our existing political institutions to respond to ever-rising inequality and the threat it poses to democracy is by no means assured,” she writes in Capitalism and the Future of Democracy. “In this context, it is encouraging that a market-based ideology appears to be on the wane. It is being challenged both by events and by new intellectual stirrings on the right and the left,” she concludes.

The “typical course in microeconomics spends more time on market failures and how to fix them than on the magic of competitive markets,” Suresh Naidu, of Columbia; Dani Rodrik, of Harvard; and Gabriel Zucman, of the University of California, Berkeley, wrote in the Boston Review earlier this year, Cassidy adds:

The “typical course in microeconomics spends more time on market failures and how to fix them than on the magic of competitive markets,” Suresh Naidu, of Columbia; Dani Rodrik, of Harvard; and Gabriel Zucman, of the University of California, Berkeley, wrote in the Boston Review earlier this year, Cassidy adds:

“The typical macroeconomics course focuses on how governments can solve problems of unemployment, inflation, and instability rather than on the ‘classical’ model where the economy is self-adjusting.” At the research level, meanwhile, “distributional considerations are making a comeback. And economists have been playing an important role in studying the growing concentration of wealth, the costs of climate change, the concentration of important markets, the stagnation of income for the working class, and changing patterns of social mobility.”

These issues have profound implications for the quality and responsiveness of democracy, Boushey adds, citing the research of political scientists Martin Gilens, of Princeton, and Benjamin Page, of Northwestern (authors of Democracy in America?: What Has Gone Wrong and What We Can Do About It and “Making American Democracy Representative), who examined almost 1800 different issues over a 20-year period and found that “policies with low support among the rich became law only about 18 percent of the time, whereas policies with high support among the rich ended up as law about 45 percent of the time.”

Their 2014 study published by Cambridge University Press concluded that “economic elites and organized groups representing business interests have substantial independent impacts on U.S. government policy, while average citizens and mass-based interest groups have little or no independent influence.”

Their 2014 study published by Cambridge University Press concluded that “economic elites and organized groups representing business interests have substantial independent impacts on U.S. government policy, while average citizens and mass-based interest groups have little or no independent influence.”

But how accurate is this narrative? Looking at modern history, has greater egalitarianism been a self-reinforcing process? The greatest period of U.S. economic equality was in the late 1970s: But this era of equality is precisely when the U.S. took a turn toward free-market conservatism, culminating in the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980, notes Bloomberg Opinion columnist Noah Smith, an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, citing several reasons to doubt Gilens and Page’s conclusion, including:

- First of all, the group that Gilens and Page label “affluent” are those making more than $146,000 a year. Although this takes in the billionaire class that socialists rail against, it mostly includes people who could hardly be considered rich.

- More importantly, the authors found a strong correlation between the preferences of this affluent group and those of the middle class — in other words, the policies that are enacted don’t often seem to buck the will of the broad public.

- Additionally, correlation doesn’t equal causation — politicians might do things that they think will benefit the overall economy, and that only coincidentally happen to please the affluent.

-

It’s also likely that Gilens and Page are just wrong. A number of other research teams have done their own studies, and most concluded that it’s the middle class, not the rich, who tend to hold sway in democratic politics. A 2015 paper by political scientist Peter Enns, for example, concludes that “policy ends up about where we would expect if policymakers represented the middle class and ignored the affluent.”

- Poverty & Freedom is available for preorder on Amazon.com and will be released on November 1, 2019.