Two great earthquakes shaped the present global order. The first, in 1989, seemed to promise an irresistible march towards liberal democracy and open markets. The opportunity was squandered by those intoxicated with their apparent triumph. A second set of seismic shocks then saw the world turn back towards nationalism and protectionism, FT analyst Philip Stephens observes:

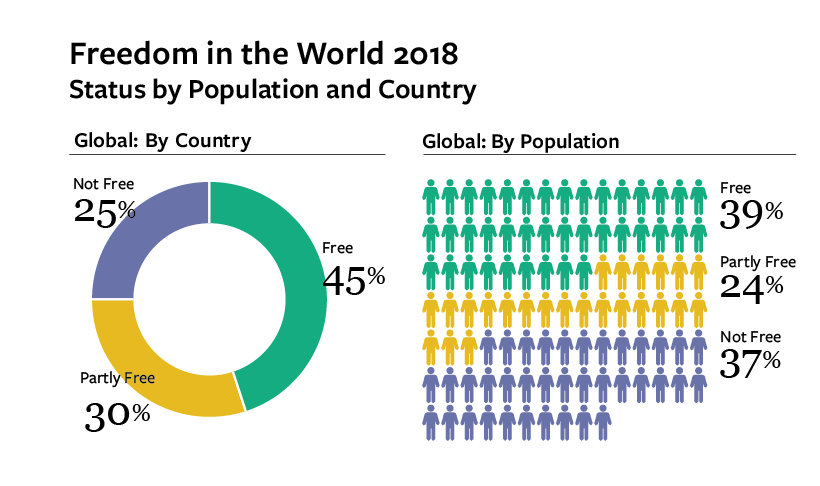

The Washington-based think-tank Freedom House’s annual survey of rights and liberties (above) pinpoints 2007 as a high-water mark, with a retreat ever since. China and Russia have grown bolder in their embrace of authoritarianism. The Arab spring has turned to winter. Nations such as Turkey, Hungary and Poland have been sliding steadily into illiberalism. Rising populism and anti-immigrant sentiment in rich western democracies, Freedom House’s 2018 report notes, have offered succour to leaders who “give short shrift to fundamental civil and political liberties”.

Some post-Communist regimes have at least started to come to terms with the legacy of totalitarianism, including complicity in the Holocaust.

Carl Gershman, President of the National Endowment for Democracy, commended Vilnius Mayor Remigijus Šimašius for his efforts to correct the narrative around Lithuania’s role in the Shoah. “There aren’t many people around the world standing for truth, standing on principle. The fact that you’re raising this standard has enormous significance,” he told an American Jewish Committee (AJC) reception.

Carl Gershman, President of the National Endowment for Democracy, commended Vilnius Mayor Remigijus Šimašius for his efforts to correct the narrative around Lithuania’s role in the Shoah. “There aren’t many people around the world standing for truth, standing on principle. The fact that you’re raising this standard has enormous significance,” he told an American Jewish Committee (AJC) reception.

The rise of illiberal populism has had a toxic impact on democratic political culture, enhancing polarization and creating an imperative to establish a new form of what Arthur M. Schlesinger called “The Vital Center,” notes one observer.

The rise of illiberal populism has had a toxic impact on democratic political culture, enhancing polarization and creating an imperative to establish a new form of what Arthur M. Schlesinger called “The Vital Center,” notes one observer.

“In a democracy, you defeat your opponent. You do not destroy him or her,” says Jeffrey Gedmin, editor-in-chief of The American Interest. “We witness in the United States—and in many places across the West—a challenge to our institutions, but also to the culture of democracy, to democracy’s habits, values, and behaviors.”

“We must look for ways to restore the broad center. Only by doing this can we push the fringes back to the extremes,” he tells Laure Mandeville, a senior reporter for Le Figaro.

The legacies of 1989 have ongoing relevance for the potential for activism in other contexts, analyst Barbara J. Falk writes for Eurozine, a partner of the National Endowment for Democracy:

The legacies of 1989 have ongoing relevance for the potential for activism in other contexts, analyst Barbara J. Falk writes for Eurozine, a partner of the National Endowment for Democracy:

- First, the legacies of 1989 are relevant to the region from which they originally arose, that is, east-central and eastern Europe. Research on ‘dissidence’ writ large, including but not limited to civil society activism and resistance to authoritarianism, allows for further interrogation and analysis of the decades before and leading up to 1989. ….

- Second, 1989 as a set of legacies allows us to ‘travel’ to other contexts where 1989 has been a precursor, a model, or an alternative example, and here I will analyse how 1989 reverberated in Egypt (or did not) in 2011 during the ‘Arab Spring’ and the ‘Velvet Revolution Redux’ in Armenia in 2018.

- Third, and finally, 1989 provides a set of legacies relevant to addressing democratic deficits and reinvigorating civil societies across the West. This is particularly the case now, when all manner of ‘hybrid threats’, both from skilled adversaries externally, and divisive illiberals and populists internally, continue to assault democracies from without and within.

But illiberal populists “offer scapegoats in place of remedies. Nor should anyone harbour illusions about authoritarian alternatives,” the FT’s Stephens adds. “The world is not flocking to imitate Moscow, Budapest and Ankara. Even as they scorn democracy, tyrants and demagogues feel compelled to pay it lip service. There is though one obvious lesson. If they want to restore authority abroad, western leaders must first rebuild credibility at home.” RTWT

Democracies must also confront the authoritarian resurgence, TAI’s Gedmin adds:

Democracies must also confront the authoritarian resurgence, TAI’s Gedmin adds:

First comes vision, then strategy, then tactics. We have lost any sense of vision. What should the region look like in five and 15 years? How do we define our interests? And those of our allies? Do we have priorities? We’ve lost our way. Exit strategy has become our vision. We are short-term, tactical, and reactive. The Russians and Iranians have a vision. They get power and influence, they play a longer game. RTWT