No empire in history has disintegrated as quickly or as bloodlessly as the Soviet one, in the remarkable year that saw the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989. Yugoslavia, never a part of that empire, followed a tragically different path; but for the rest of central and eastern Europe, though clearly imperfect, the past 30 years have been a time of marvels, the Economist notes:

Standards of living for most of the region’s peoples have vastly improved, and most of them know it. New polling by the Pew Research Centre shows that 81% of Poles, 78% of Czechs and 55% of Hungarians agree that this is the case. Only Bulgarians on balance take a gloomy view, with just 32% of them thinking that their standard of living has improved since 1989…. In Hungary and Poland those who feel left behind tend to blame liberalism and the West.

With the collapse of Communism, “the ‘ideological lie’ had been exposed as the chimera it had always been, and the peoples behind the Iron Curtain cried out for a ‘normal’ existence, freed from violence, lawlessness, and systematic mendacity,” Daniel J. Mahoney writes for Law & Liberty. “The economic motives and concerns were real but secondary. People can tolerate poverty, at least to some extent, but not the spiritual poverty of a regime built on force and deception.”

With the collapse of Communism, “the ‘ideological lie’ had been exposed as the chimera it had always been, and the peoples behind the Iron Curtain cried out for a ‘normal’ existence, freed from violence, lawlessness, and systematic mendacity,” Daniel J. Mahoney writes for Law & Liberty. “The economic motives and concerns were real but secondary. People can tolerate poverty, at least to some extent, but not the spiritual poverty of a regime built on force and deception.”

The result was a quite paradoxical moment for democracy, notes Luke Cooper (@lukecooper100), a Visiting Fellow on the Europe’s Futures program at Vienna’s Institute of Human Sciences and an Associate Researcher at the LSE Conflict and Civil Society research unit. As a system of representative governance, it was more widespread than ever before. Yet, as conflicts over big ideological ideas were pushed to one side by the unfettered rise of neoliberalism, the representative function of the democratic system was diminished. Two key dangers presented themselves, he writes for the LSE blog:

- Firstly, the existence of communism had acted as a moderating force on capitalism. Once it was no longer a threat to the status quo there was less incentive for capital to compromise with labour.

- Secondly, if the purposefulness of democracy became less clear to voters, then participation was likely to decline. Ultimately, radical criticisms of liberal democracy might re-emerge. If citizens grew disillusioned they may end up rejecting democratic processes.

As if to mock the triumphalism of 1989, liberal democracy has faltered with stunning abruptness, says analyst Robert Kuttner. For both the far left and the far right, recent events are evidence that liberal democracy is inherently flawed and even doomed, he writes for the New York Review of Books:

As if to mock the triumphalism of 1989, liberal democracy has faltered with stunning abruptness, says analyst Robert Kuttner. For both the far left and the far right, recent events are evidence that liberal democracy is inherently flawed and even doomed, he writes for the New York Review of Books:

To Marxist critics, parliamentary democracy was always a smokescreen for the rule of capital, and the current travails of democracy mean we have reached the terminal crisis of capitalism at last. Even non-Marxist progressive economists like Joseph Stiglitz and Dani Rodrik agree that we can’t have both unrestrained global capital and a functioning democratic nation-state. Among traditionalist conservatives who cherish an organic conception of society—as opposed to free-marketeers—liberal democracy is a dangerous betrayal of deeper sources of culture and civilization such as the family, the tribe, the nation, and the church.

A parochial narrative, common in the West, concerns the ‘backlash’ narrative: post-communist publics disenchanted with a combination of capitalism, corruption and multiculturalism embrace populist leaders promising to restore national sovereignty and conservative values. The interpretation is fine as far as it goes, but what about analogous developments beyond Europe? Eurozine’s Simon Garnett asks:

A parochial narrative, common in the West, concerns the ‘backlash’ narrative: post-communist publics disenchanted with a combination of capitalism, corruption and multiculturalism embrace populist leaders promising to restore national sovereignty and conservative values. The interpretation is fine as far as it goes, but what about analogous developments beyond Europe? Eurozine’s Simon Garnett asks:

Is ’89 significant solely as the beginning of a story that ends with Orbán and Kaczyński? This is the question that Ivan Krastev and Stephen Holmes set out to answer in their new book The Light that Failed. They argue that resistance to the imperative to imitate the West – above all Germany – drives support for populists in Hungary and Poland, but plays out differently in Russia, where yearning for superpower status translates into a politics of aggressive ‘mirroring’.

Eurozine

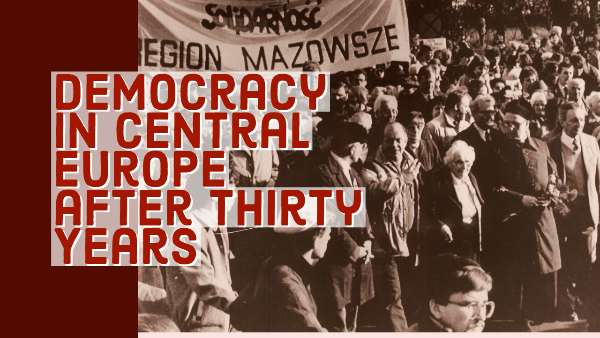

The triumph of Poland’s Solidarity trade union movement in 1989 stands out as one of the most consequential victories for human freedom of this or any other century. Not only did it liberate the Polish people from the yoke of communism, but it also set in motion the events leading to the fall of the Berlin Wall, the collapse of communism in Central Europe and the Soviet Union, and the end of the Cold War.

Thirty years later, the National Endowment for Democracy invites you to a conference commemorating The 30th Anniversary of the Historic Democratic Transitions in Poland and Central Europe. RSVP

Thursday, November 14, 2019. 9:00 a.m.– 12:15 p.m.

1025 F St. NW, Suite 800, Washington, DC 20004

8:30 a.m. Registration and Continental Breakfast

9:00 a.m. Welcome and Opening Remarks

Carl Gershman, President of the National Endowment for Democracy

Carl Gershman, President of the National Endowment for Democracy

Robert Destro, Asst. Secretary of State for Democracy, Human Rights and Labor

Keynote Addresses

The Triumph and Legacy of Solidarity

Lech Walesa, Founder of Solidarity and the Former President of Poland

Introduced by AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka

Poland’s Political and Economic Transition

Poland’s Political and Economic Transition

Leszek Balcerowicz, Former Deputy Prime Minister of Poland.

Introduced by CIPE Board Chairman Greg Lebedev

Panel Discussion: Defending Democracy in Poland and Central Europe

Anne Applebaum, Author and Historian

Victoria Nuland, Former Assistant Secretary of State for Europe

Simon Panek, Executive Director, People in Need, Czech Republic

George Weigel, Author and Biographer of Pope John Paul II

Moderator: Daniel Fried, Former US Ambassador to Poland