Radical Islamist extremist violence is wracking the fragile state of Burkina Faso and spreading east, The Washington Post reports:

Nearly 1,000 civilians were killed in 2019 by local militias and fighters linked to Islamic extremists, a spike in attacks of nearly 190%, according to the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project, which collects and analyzes conflict information. The violence in northern and now eastern Burkina Faso has displaced more than half a million people, according to the United Nations. And there are fears the unrest could throw elections planned for late 2020 into question.

“The terrorist attacks are worsening, they’re getting closer to the capital and the real challenge is that we can’t see the response from the government,” said Siaka Coulibaly, an analyst with the Center for Public Policy Monitoring by Citizens.

Extremist attacks will grow in lethality, sophistication, and scope across the Sahel in 2020, argues CSIS analyst Marielle Harris:

As the security crisis deepens, international actors will scramble to devise more effective strategies. In early 2020, French president Emmanuel Macron is reevaluating his country’s military involvement, asking leaders of Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger to “clarify and formalize” their demands of French military assistance amid growing anti-French sentiment. Meanwhile, the Trump administration is seeking to recalibrate its position from expansion—creating a special envoy and interagency taskforce—to withdrawal, mulling a proposal to pull military officers from the region. These realignments raise crucial questions about the future of international engagement in the Sahel.

Iraq is another arena where extremist violence threatens to undermine a fragile state.

The current political crisis in Iraq allows external powers to disregard the county’s sovereignty and act with impunity, said Laith Kubba (right), an adviser to Iraqi Prime Minister.

“The core issue for Iraqis is that currently the Government and state is so weak that both America and Iran feel comfortable to violate that sovereignty.”

But Kubba – a former MENA director at the National Endowment for Democracy – rejected calls for a U.S. withdrawal.

“No Iraqi would simply like American troops to leave Iraq for Iraq to be more or less under Iran and then for Iraq to be unstable because Daesh (ISIS) is back,” he explained.

The assassination of Qasem Soleimani represents a tectonic shift in U.S. policy in Iraq, argues Ranj Alaaldin, Visiting Fellow in the Brookings Doha Center and Director of the Proxy Wars Initiative. The complexities of Iraqi politics, the failures of the reconstruction process, and the state-building process in the country more generally has been particularly kind to Shia militia groups, which have thrived as a result of the state’s fragility and a fractious political landscape.

“There is now unlikely to be any serious prospect of achieving good governance and reform in Iraq, and we may be witnessing the end of Iraq’s fragile democracy,” he contends. “Soleimani’s assassination represents the death knell of the civilian-led reform movement that has gripped the country in recent months.”

Fragility is often defined as the breakdown in the social contract between state and society, the National Democratic Institute’s Lauren van Metre adds. In the case of violent extremism, this breakdown creates “fertile ground for extremists’ attempts to create alternative political orders,” according to a USIP Task Force report, in the face of “community alienation by an oppressive, corrupt or unresponsive government.” In the case of extreme poverty, as identified by the Commission on State Fragility, Growth and Development (the Cameron Report) the governments of fragile states “lack the legitimacy and capacity to deliver the jobs, public services, and opportunities their people need.” The UK’s Cameron report on Escaping the Fragility Trap came to a similar conclusion.

Fragility is often defined as the breakdown in the social contract between state and society, the National Democratic Institute’s Lauren van Metre adds. In the case of violent extremism, this breakdown creates “fertile ground for extremists’ attempts to create alternative political orders,” according to a USIP Task Force report, in the face of “community alienation by an oppressive, corrupt or unresponsive government.” In the case of extreme poverty, as identified by the Commission on State Fragility, Growth and Development (the Cameron Report) the governments of fragile states “lack the legitimacy and capacity to deliver the jobs, public services, and opportunities their people need.” The UK’s Cameron report on Escaping the Fragility Trap came to a similar conclusion.

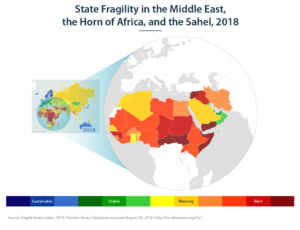

The Islamic State’s resurgence in parts of Iraq and Syria and the sharp increase in terrorism in the Sahel serve as stark reminders that the underlying conditions that foment extremist violence remain firmly in place, the United States Institute of Peace reports:

In its final report to Congress, the USIP-convened Task Force on Extremism in Fragile States concluded that the United States can no longer rely solely on counter-terrorism to stave off the threat of violent extremism. Rather, to get ahead of the challenge, the U.S. must focus on eradicating terrorism’s root causes by encouraging good governance and political reforms in fragile states. As more research reveals the linkages between poor governance, instability, and violence, the international policy community must develop a shared understanding of how support for responsive and responsible governance in fragile states can prevent violent extremism.

Credit: USIP

USIP, the National Democratic Institute, and the George W. Bush Institute (above) discuss the way forward following the adoption of the Global Fragility Act and donor support for political transitions out of fragility.

“History tells us that states with more democratic characteristics are usually more prosperous, stable, and reliable partners,” the conference heard.

“They’re better strategic partners because their citizen-centered, making them less likely to produce terrorists, proliferate weapons of mass destruction or engage in armed aggression,” said USAID Administrator Mark Green. “Conversely, authoritarian regimes are, at best, unreliable partners and, at worst, pose significant risks to peace and stability,” he added. RTWT

On the subject of turmoil in the Middle East, watch @fiu_sipa‘s State of the World 2020 panel, with @NEDemocracy partner• POMED’s Stephen McInerney @newamerica‘s @SlaughterAM @JohnsHopkins‘ Eric Edelman @Stanford‘s @NancyGEO @McCainInstitute‘s @NicholasRasmu15