As Chinese leader Xi Jinping landed in Myanmar on Friday he hoped to send a clear signal that his country is back in the driver’s seat. Having backed Myanmar, also known as Burma, while Western nations recoiled at its atrocities against the Rohingya, Xi is poised to cash in by reviving stalled strategic projects that would deepen Beijing’s reach into the Indian Ocean, The Washington Post reports:

As Chinese leader Xi Jinping landed in Myanmar on Friday he hoped to send a clear signal that his country is back in the driver’s seat. Having backed Myanmar, also known as Burma, while Western nations recoiled at its atrocities against the Rohingya, Xi is poised to cash in by reviving stalled strategic projects that would deepen Beijing’s reach into the Indian Ocean, The Washington Post reports:

The method is a familiar one for Beijing: Where the West is taking a moral stance or retreating, China’s Communist leaders step in with promises, goodies and demands of their own in pursuit of a strategic advantage.

“China is declaring it has regained its position in Burma and repaired its damaged influence,” said Yun Sun, director of the China Program at the Stimson Center. “This of course has happened in the wake of the Rohingya crisis. Burma is getting a top visit at a time where it has returned to pariah status in the eyes of the rest of the international community.”

However…..

“Myanmar won’t be back in China’s pocket,” said Stimson’s Sun. “The Burmese and the NLD government are using American acquiescence and Chinese desire to gain influence in Myanmar to their own advantage.”

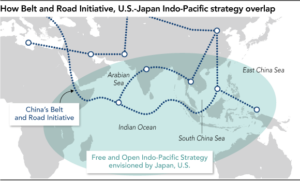

China’s big-money push to build ports, rail lines and telecommunications networks around the world – and increase Beijing’s political sway in the process – seemed to be running out of gas just a year ago. Now the program, called the Belt and Road Initiative, has come roaring back. Western officials and companies, for their part, are renewing their warnings that China’s gains in business and political clout could come at their expense, The New York Times reports.

China’s big-money push to build ports, rail lines and telecommunications networks around the world – and increase Beijing’s political sway in the process – seemed to be running out of gas just a year ago. Now the program, called the Belt and Road Initiative, has come roaring back. Western officials and companies, for their part, are renewing their warnings that China’s gains in business and political clout could come at their expense, The New York Times reports.

The move could raise tensions with the US, which worries that China is building a bloc of nations that will mostly buy Chinese goods and tilt toward China’s authoritarian political model, observers suggest.

But figures for BRI over the past year point to a smaller scale of actual Chinese outbound investment and overseas contracting for construction projects with less strain on Chinese finances, writes RFA analyst Michael Lelyveld. The latest figures reflect a downturn in both ODI and BRI investment, despite perceptions of rapid expansion overseas. The decline in the official numbers understates the extent of the drop, said AEI resident scholar Derek Scissors.

“The conventional wisdom is behind the trend on weaker Chinese spending. BRI has been overhyped from the beginning and now includes dozens of countries that should expect little in the way of Chinese activity,” Scissors said.

“The conventional wisdom is behind the trend on weaker Chinese spending. BRI has been overhyped from the beginning and now includes dozens of countries that should expect little in the way of Chinese activity,” Scissors said.

China is the state that appears to be pursuing geopolitical ideas most aggressively, argues Jeremy Black, a 2018 Templeton Fellow and Professor of History at Exeter University. Resting on the Maoist perception that foreign pressure had held China’s development back, there was a determination to project power, both in order to prevent that situation and so as to be able to impose it on others, he writes for the Foreign Policy Research Institute.

China has been taking steps to strengthen its economic and technological position in Europe. What are the implications? According to RAND experts Ali Wyne and Scott W. Harold, the more of a foothold that China gains across the continent, the more it will be able to challenge political sovereignty and intellectual freedom there.

In the January 2020 issue of the NED’s Journal of Democracy, available free of charge through February 15 at Project MUSE,….

In the January 2020 issue of the NED’s Journal of Democracy, available free of charge through February 15 at Project MUSE,….

- Minxin Pei writes that the course chosen decades ago by Deng Xiaoping has enabled a “revival of neo-Stalinism” in Xi Jinping’s China;

- Andrew J. Nathan probes the puzzle of popular support for authoritarian regimes in East and Southeast Asia.

If it is not to lose its strategic struggle with China in Asia and globally, the United States needs to present an alternative model to Beijing’s authoritarian archetype, according to a new report (left) released this week.

If it is not to lose its strategic struggle with China in Asia and globally, the United States needs to present an alternative model to Beijing’s authoritarian archetype, according to a new report (left) released this week.

U.S. alliances and partnerships across the Atlantic and in the Indo-Pacific anchor the postwar order—a system that has long underpinned U.S. preeminence, say former Penn Kemble fellow Wyne and Harold. China assesses that it will be better positioned to compete with the United States if it can weaken those relationships through a combination of economic attraction and coercion. While that undertaking is more readily observable (PDF) in the Indo-Pacific, it is increasingly apparent in Europe as well.