BPFG

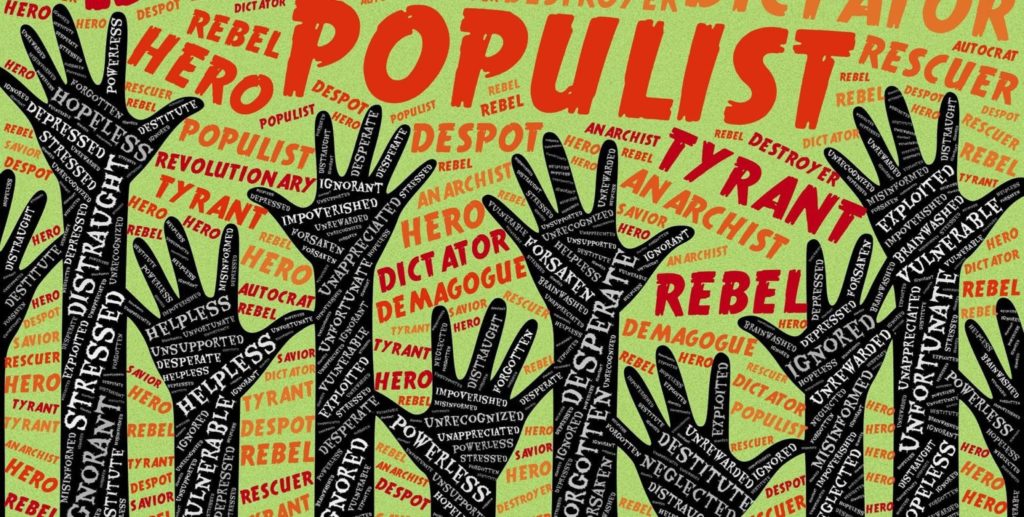

Populist politics tilts authoritarian. In sweeping away supposedly corrupt elites and institutions, the populist leader weakens all forces standing in his way. Critics becomes enemies, constitutional constraints become obstacles to democracy, and the tyranny of the majority becomes a virtue, not a vice, note analysts

Populism is not hospitable to grand strategy, they write for Foreign Affairs:

- First, populism accentuates internal divisions. Polarizing by design, it narrows the sphere of the supposedly authentic people so that, within the nation as a territorial and legal entity, there can be no unity.

- Second, populist politicians regularly mobilize the people in righteous anger against enemies. When heated rhetoric is in the air, emotional responses to the crisis of the day threaten to overtake rational strategy. Strategy becomes less supple, as leaders have trouble pursuing conciliatory tactics in a climate of affront and retribution.

- Finally, populism concentrates authority in the charismatic leader. It disempowers bureaucrats and institutions that can check fickle rulers and block extreme decisions. … If the populist leader does pursue something akin to a grand strategy, it will not outlive his rule.

Is there a recipe for defeating a populist? @FMichaelWuth and @MelvynIngleby ask in an article for the National Endowment for Democracy’s @JoDemocracy, “The Pushback Against Populism: Running on ‘Radical Love’ in Turkey.”

Is there a recipe for defeating a populist? @FMichaelWuth and @MelvynIngleby ask in an article for the National Endowment for Democracy’s @JoDemocracy, “The Pushback Against Populism: Running on ‘Radical Love’ in Turkey.”

The conservative writer Bret Stephens recently defined populism as the triumph of democracy over liberalism, by which he meant the triumph of majoritarian democracy over its liberal constraints, adds Princeton University’s Michael Walzer. Liberal democracy sets limits on majority rule—usually with a constitution that guarantees individual rights and civil liberties, establishes an independent judicial system that can enforce the guarantee, and opens the way for a free press that can defend it. Majorities can only act, or act rightly, within constitutional limits.

National Endowment for Democracy

Most of uses of the adjective “liberal” are not relevant today. But {some} seem to me not only relevant but critically important for contemporary politics, he writes for Dissent:

We need liberal democrats to fight against the new populism; liberal socialists to fight against the frequent authoritarianism of left-wing regimes; liberal nationalists to fight against contemporary xenophobic, anti-Muslim, and anti-Semitic nationalisms; liberal communitarians to fight against the exclusivist passions and fierce partisanship of some “identity” groups; and liberal Jews, Christians, Muslims, Hindus, and Buddhists to fight against the unexpected return of religious zealotry.

These are among the most important political battles of our time, and the adjective “liberal” is our most important weapon, Walzer insists.