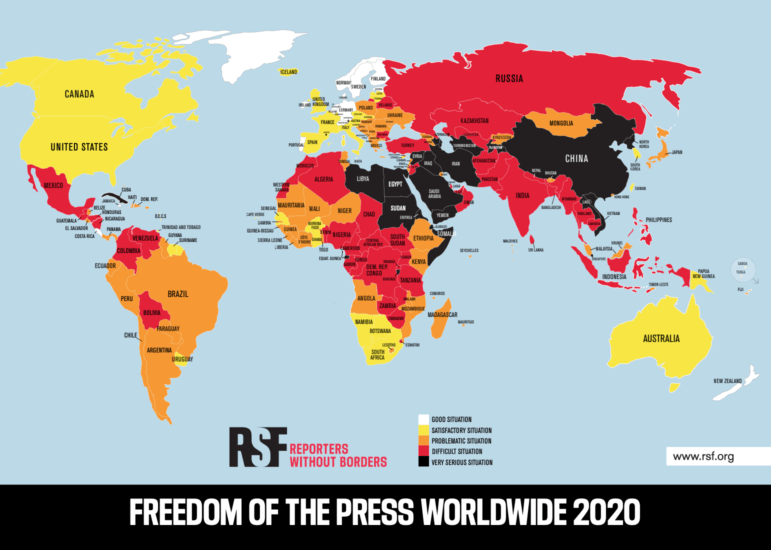

The novel coronavirus is compounding preexisting threats to press freedoms around the world, according to a new report by the international watchdog organization Reporters Without Borders, ABC News reports:

The novel coronavirus is compounding preexisting threats to press freedoms around the world, according to a new report by the international watchdog organization Reporters Without Borders, ABC News reports:

Reporters Without Borders, also known by its French acronym RSF, released its annual ranking of countries based on the strength of their press freedoms last week, highlighting several countries – including Iran (ranked 173rd) and China (ranked 177th) – whose poor rankings reflect the way those governments “censored their major coronavirus outbreaks extensively.”

“Iran and China are two countries that saw the biggest outbreaks early on, and they’re the two countries where you didn’t really see journalists being able to operate,” Dokhi Fassihian, Executive Director of Reporters Without Borders USA, told ABC News. “I don’t for a minute believe the numbers they’re reporting.”

Credit: ACUS

But a pandemic also “weakens the hands of authoritarian leaders,” former national security adviser H.R. McMaster told a Hoover Institution web briefing. Liberal democracies have an opportunity to change course in a crisis through elections,and can assess such changes through free and open political debate. Authoritarians have no such safety valve. When citizens lose faith in their leader, the only recourse is revolution or coup, Bloomberg’s Eli Lake reports:

Russian President Vladimir Putin, McMaster predicted, will be blamed by his people and elites for the drop in world oil prices because of Russia’s role in spiking production in February and March. In Iran, McMaster said, leaders will continue to face a serious legitimacy crisis. …Iran’s “servile relationship” with Beijing prevented it from cutting off travel from China as the virus was spreading, supercharging Iran’s outbreak, among the world’s most severe.

The assumption that there is a tension between liberal democratic values and strong, effective responses to public health crises is profoundly dangerous, analyst Jeffrey Smith and Nic Cheeseman write for Foreign Policy.

Yet efforts to analyze and explain state responses to the Covid-19 pandemic purely in terms of regime type are misleading and misguided, says a leading analyst.

Yet efforts to analyze and explain state responses to the Covid-19 pandemic purely in terms of regime type are misleading and misguided, says a leading analyst.

If competence varies widely within the same type of regime, then regime type alone cannot possibly be determinative of outcomes, argues Adam Garfinkle, a Distinguished Visiting Fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies at the Nanyang Technological University in Singapore:

Autocratic governments can be effective and not, just as democratic governments can be effective and not in a public health crisis. More important, perhaps, we use the terms authoritarian/autocratic and democratic as if they really mean anything anymore. Now that the international environment’s center of gravity has become increasingly de-Westernized, these terms are really showing their lack of conceptual coherence.

In a post-Covid future, some countries and non-state actors will be tempted to seek the capacity to create plagues, and every country will need to defend against them, notes analyst Walter Russell Mead. The ability to recognize new diseases quickly and to develop treatments and vaccines has become a cornerstone of national defense.

In a post-Covid future, some countries and non-state actors will be tempted to seek the capacity to create plagues, and every country will need to defend against them, notes analyst Walter Russell Mead. The ability to recognize new diseases quickly and to develop treatments and vaccines has become a cornerstone of national defense.

Resilience also matters. Hardening cities, health systems, businesses and supply chains to make them less vulnerable to disruption must be a priority for the future, he writes for the Wall Street Journal.

The present crisis is an economic as well as a medical one, which makes it necessary to balance the needs of public health, on which the physicians have the expertise, against the requirements for national economic well-being, adds Michael Mandelbaum, Professor Emeritus of American Foreign Policy at The Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies. Only democratically-elected officials have the political legitimacy to strike that balance, he observes in the American Interest,

National Endowment for Democracy (NED) board member Eileen Donahue participated in a PEN America webinar on how to reconcile citizens’ civil liberties with the robust surveillance required to monitor and predict the spread of Covid-19. Fellow NED board member Michele Dunne joined fellow member of the Egypt Working Group in calling for the release of American citizens and permanent residents wrongfully detained in Egypt, who are in imminent danger due to Covid-19.

National Endowment for Democracy (NED) board member Eileen Donahue participated in a PEN America webinar on how to reconcile citizens’ civil liberties with the robust surveillance required to monitor and predict the spread of Covid-19. Fellow NED board member Michele Dunne joined fellow member of the Egypt Working Group in calling for the release of American citizens and permanent residents wrongfully detained in Egypt, who are in imminent danger due to Covid-19.

Some observers will come to view the pandemic as “a happy capitalist parable of how markets solved it all, or a happy socialist parable of how we all came to terms with a commanding state, or a happy libertarian parable about how we didn’t need the state at all because self-organizing citizens were enough,” notes Eric Liu, co-author, with Nick Hanauer, of The Gardens of Democracy: A New American Story of Citizenship, the Economy, and the Role of Government. His recent book is You’re More Powerful Than You Think: A Citizen’s Guide to Making Change Happen.

“That’s fine,” he writes for Democracy. “But the point is, none of us can get our preferred happy ending unless we show up as neighbors and citizens and voters to imagine and animate a better future” – what he calls “the spirit of a democracy that’s going to survive.”

BTI

The Bertelsmann Transformation Index @bti_project launches the #BTI2020 this Wednesday, April 29, with 137 country reports, analyses, an updated Transformation Atlas, and an interactive data visualization tool all on a new website bti-project.org.

We are left with the recognition that path dependencies defined by the wells of historical experience incline particular countries toward certain regime types. But the diversity of political cultures even within regime-type categories is still so great that no causal straightjacket crisply binds together performance outcomes, Garfinkle writes for the American Interest:

It’s just a fact that some societies are more rule-abiding by dint of their historical conditioning than others. It’s just a fact, too, that some societies have deeper rule-of-law liberal bases than others. That is why deep-rooted democratic societies can put in place temporary emergency control measures to deal with a crisis and not forget that they are temporary. More shallow-rooted ones, like the post-Cold War nationalist regimes in Hungary and Poland, for example, may not see that distinction, or may want to lose sight of it, the better to use a crisis for purposes of grabbing more power, just as non-democratic regimes tend to do. These difference do not track with an authoritarian-democratic divide. Their true sources are more likely to be shapers of that divide, such as it is.

It’s just a fact that some societies are more rule-abiding by dint of their historical conditioning than others. It’s just a fact, too, that some societies have deeper rule-of-law liberal bases than others. That is why deep-rooted democratic societies can put in place temporary emergency control measures to deal with a crisis and not forget that they are temporary. More shallow-rooted ones, like the post-Cold War nationalist regimes in Hungary and Poland, for example, may not see that distinction, or may want to lose sight of it, the better to use a crisis for purposes of grabbing more power, just as non-democratic regimes tend to do. These difference do not track with an authoritarian-democratic divide. Their true sources are more likely to be shapers of that divide, such as it is.

The conclusion is clear, Garfinkle contends: No matter which sets of countries one chooses to compare, no significant patterns stuck in ideological concrete exist; other factors mainly shape the outcomes.

Competitors to the liberal order are treating the coronavirus crisis as an opportunity to exploit for their advantage, the Hudson Institute adds. But the crisis is also an opportunity to prove the resilience of democracy and could drive new demands for freedom. Join a discussion (below) on what the ongoing crisis means for the future of global democracy and what the United States and allies can do to protect freedom around the world.