Former NED board member Francis Fukuyama

In human history, national emergencies, whether caused by war, invasion, financial crisis, or an epidemic, have often been the occasions for major political reform. It takes a huge external shock to get people to recognize they have a common problem, and that extraordinary measures will be required to get out of it, Stanford University’s Francis Fukuyama (right) observes.

If one looks at the different degrees of success of countries around the world fighting the pandemic, two factors emerge as critical, he writes for the American Interest:

- The first is the degree of state capacity at their disposal, which has to do with the numbers of health workers, emergency responders, infrastructure, and available resources.

- The second critical factor has to do with the degree of trust that citizens have in their government. All countries need to rely on a high degree of voluntary compliance with the state’s rules, whether they are democratic or authoritarian. They are in big trouble if they have to rely on coercive enforcement, something American governors need to keep in mind.

Germany and South Korea are democracies where this degree of trust exists, and they have outperformed many of their neighbors as a result, Fukuyama adds.

The Economist

In the short term, the new coronavirus is likely to assist leaders with authoritarian inclinations, argues Ruth Ben-Ghiat, Professor of History and Italian Studies at New York University and the author of the forthcoming book Strongmen: From Mussolini to the Present. Authoritarians demand a society structured around vertical bonds between the leader and the people, she writes for Foreign Affairs. But…..

The social distancing required by the pandemic may lead to a new appreciation of the preciousness of the horizontal bonds that are crucial to the health of democracy. Those who desire more accountable, transparent, and compassionate leadership are sheltering at home right now, but they may emerge stronger and more united from this collective experience. Leaders now using the pandemic for personal gain will then have to reckon with the costs of their actions.

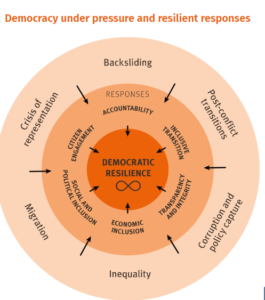

International IDEA

The post-corona virus world is already here, argues Josep Borrell, the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy. This will be test of democratic resilience since crises always show societies where their strengths and weaknesses lie. Political narratives are already being written to prepare for what comes next, he writes for the European Council on Foreign Relations, citing three competing narratives:

- In theory, the populist narrative ought to be severely affected by this crisis, as it brings the

importance of a rational approach, expertise, and knowledge into sharp focus –

principles that the populists mock or reject as they associate all of those qualities

with the elite. …. But the populists can, first and foremost, blame foreigners for spreading the virus. They can also point the finger at globalisation…. - The authoritarian narrative is similar to the populist narrative in that it seeks to

simplify problems and provide one central explanation for them all. It takes the line

that only authoritarian and centralised regimes can defeat the pandemic by

mobilising all of a country’s resources. But we know this to be false. …. - That leaves the democratic narrative. This one is the hardest to put together, since

doubting, questioning, deliberation, and debate are the foundations of democratic

societies. All of which hinder swift and effective action based on a clear and

indisputable narrative….

![]() Recent developments have civil society groups — like community groups, nongovernmental organizations, unions, charitable organizations, faith-based organizations, and foundations — sounding the alarm in the name of democracy, according to a new analysis.

Recent developments have civil society groups — like community groups, nongovernmental organizations, unions, charitable organizations, faith-based organizations, and foundations — sounding the alarm in the name of democracy, according to a new analysis.

The International Center for Not-for-Profit Law has launched a covid-19 Civic Freedom Tracker. The concern is that the pandemic serves as an excuse for governments to impose restrictions — many of them long in the making — that they will be hard-pressed to relinquish, according to Kristin M. Bakke, professor of political science and international relations at University College London (UCL), Neil J. Mitchell, professor of international relations at UCL, and Hannah M. Smidt, head of international security, peace and conflict in the Department of Political Science, University of Zurich.

Our research demonstrates that government restrictions are often subtle, ranging from outright bans to bureaucratic hurdles, and have proved effective at silencing voices that bring international attention to governments’ bad behavior, they write for the Post:

Civil society organizations are remarkably resilient. However, we find that as restrictions accumulate, they reduce the international spotlight on governments’ human rights violations. ….Our studies suggest that governments impose these restrictions to hide policy failures and that restrictions tend to stick — governments have incentives to keep them in place. Civil society may not emerge intact from pandemic lockdowns in some countries. And that may have detrimental consequences for government accountability.

National Endowment for Democracy

Illiberalism is its own type of disease; as governments normalize less liberal standards of governance, other countries may be similarly infected with the illiberal plague, adds analyst Maggie Tennis.

It is wishful thinking that the societal changes resulting from the pandemic will not have a significant or long-term effect on the health of democratic institutions and governance, she writes for the nonpartisan Foreign Policy Research Institute. All over the democratic world, shifting standards of government and technology may reinforce the last decade’s trend toward illiberalism.

Populists are entrenching their power around the world in the furnace of the covid emergency, says FT diplomatic correspondent Michael Peel. Existential threats including disease, climate change and mass inequality need urgent attention and an unsparing focus. If we are to mitigate these problems, we need to recognise them for what they are rather than follow fake narratives about them broadcast by dissembling rulers, he writes for Politics – UK:

Populists are entrenching their power around the world in the furnace of the covid emergency, says FT diplomatic correspondent Michael Peel. Existential threats including disease, climate change and mass inequality need urgent attention and an unsparing focus. If we are to mitigate these problems, we need to recognise them for what they are rather than follow fake narratives about them broadcast by dissembling rulers, he writes for Politics – UK:

This is why the coronavirus pandemic is such a significant moment and a potential chance to unmask the fabulists. A pandemic that cannot be held at bay with mere rhetoric ought to expose denialists and peddlers of false remedies. It is the theory of the ‘Chernobyl moment’, a reference to how the scale of the catastrophe at the Soviet-era nuclear power plant outstripped the regime’s ability to cover it up.

COVID-19 exposed the vulnerability of small- and medium-sized businesses as well as that of millions of families without secure tenure or adequate housing globally, the Center for International Private Enterprise (CIPE) adds.

COVID-19 exposed the vulnerability of small- and medium-sized businesses as well as that of millions of families without secure tenure or adequate housing globally, the Center for International Private Enterprise (CIPE) adds.

As they struggle to remain afloat, the issue of lacking or insecure property rights has come to the fore, adding to the challenges of recovery but also as a key priority for post-crisis reform. In particular, women traders in the informal sector have seen dispossession and harassment in large part due to the lack of secure property rights and weak rule of law. CIPE – a core institute of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) – and a panel of expert speakers discuss best practices and challenges in making property rights broadly accessible and economically transformative, especially for women and marginalized groups. RSVP