China has adopted a proactive and strategic approach to embrace the age of artificial intelligence (AI) as part of a digital technology package that the regime has actively employed not only to improve public service, but also to strengthen its authoritarian governance, says analyst

China has adopted a proactive and strategic approach to embrace the age of artificial intelligence (AI) as part of a digital technology package that the regime has actively employed not only to improve public service, but also to strengthen its authoritarian governance, says analyst

China’s digital progress benefits from its huge internet market, strong state power and weak civil awareness, making it more competitive than western democratic societies where privacy concern restricts their AI development, he writes in Artificial intelligence and China’s authoritarian governance, an article for International Affairs.

However, China’s ambitious AI plan contains considerable risks; its overall impact depends on how AI (the subject of a recent report from NED’s International Forum – above) affects major sources of political legitimacy including economic growth, social stability and ideology. China’s approach is gambling on its success in…

(a) delivering a booming AI economy

(b) ensuring a smooth social transformation towards the age of AI and

(c) proving ideological superiority of its authoritarian and communist values.

China was found to have the world’s worst conditions for internet freedom for the sixth consecutive year, with global internet freedom deteriorating for the fourth year running, a new Freedom House analysis reports.

Just as the G-7 came to guide multilateral action among the world’s leading economies, a set of techno-democracies—countries with top technology sectors, advanced economies, and a commitment to liberal democracy—must take action on contemporary digital issues. So far, these leading states have acted independently, but their combined market power and national strength would make them a potent unified force, according to Jared Cohen and Richard Fontaine.

Given the deep need for coordination among like-minded states, this “T-12” group of techno-democracies would fill a yawning gap in modern technological and geopolitical competition….In a more ambitious step, they could exchange information about online propaganda, disinformation, the integrity of academic research, and specific ways in which autocratic regimes employ technology to erode liberal democracy, they write in Uniting the Techno-Democracies, an article for Foreign Affairs:

Beyond helping the democracies get on the same page as they compete with China, the T-12 could also serve as a way for members to air differences within the group itself. ….. The democracies have varied approaches to data protection, privacy, and free speech. The T-12 would allow them to explore these differences, with the ultimate aim of establishing broad principles, understanding disagreements, and narrowing the gaps between participants…. More broadly, the T-12 should articulate a vision of the future based on innovation, freedom, democratic collaboration, and liberal values.

Deceptive sites that masquerade as journalism were the focus a new analysis from the Digital New Deal project of the German Marshall Fund of the United States. Identified in the GMF’s Roadmap for Securing Digital Democracy as “trojan horses”, such sites that take on the appearance of legitimate news sources but launder disinformation while eschewing the practices of independent journalism (e.g., sourcing, mastheads, verification, corrections).

Deceptive sites that masquerade as journalism were the focus a new analysis from the Digital New Deal project of the German Marshall Fund of the United States. Identified in the GMF’s Roadmap for Securing Digital Democracy as “trojan horses”, such sites that take on the appearance of legitimate news sources but launder disinformation while eschewing the practices of independent journalism (e.g., sourcing, mastheads, verification, corrections).

These sites degrade democratic debate by leveraging platform design to boost conspiracies, say GMF analysts Karen Kornbluh, Adrienne Goldstein and Eli Weiner. They found that the level of engagement with articles from outlets that repeatedly publish verifiably false content has increased 102 percent since the run-up to the 2016 election. RTWT

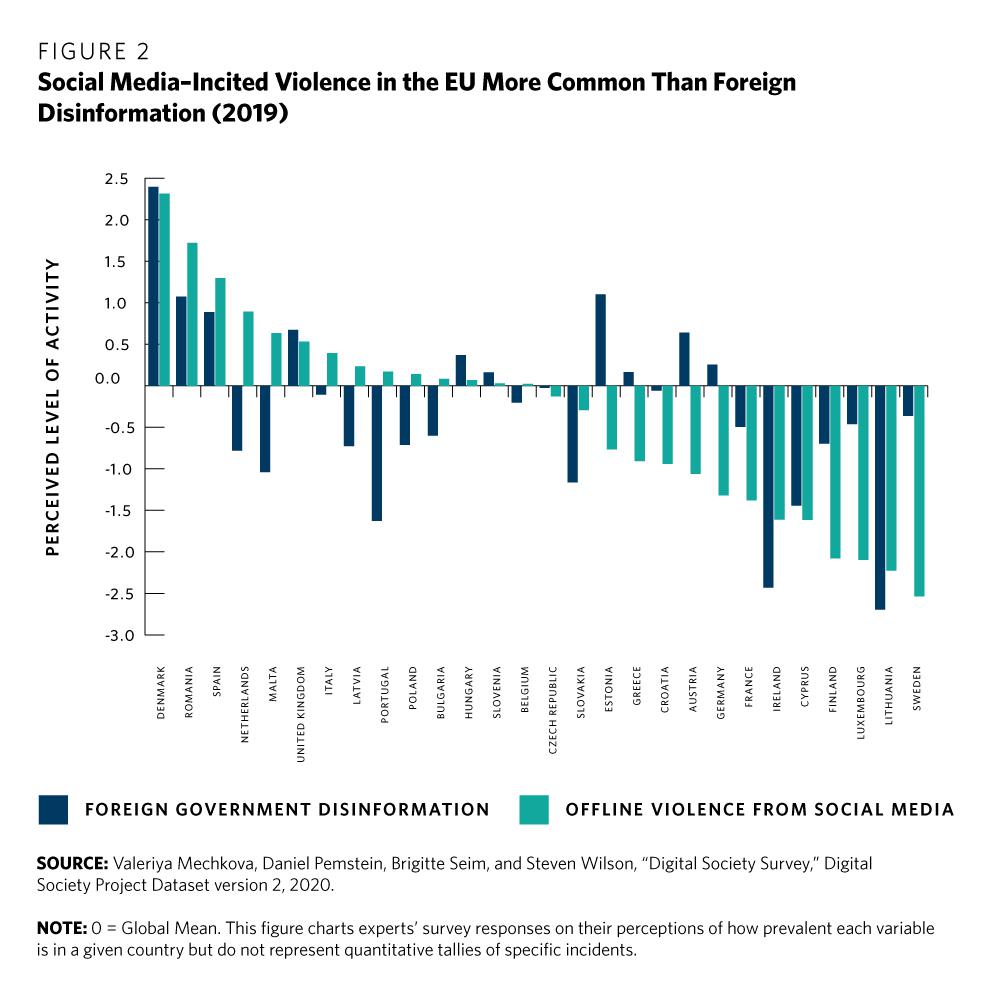

Before the end of 2020, the European commission plans to release two major policies—the European Democracy Action Plan (EDAP) and the Digital Services Act (DSA)—laying out clear principles for how it will respond to rampant disinformation, election interference, and broader concerns about a lack of accountability and transparency by online platforms as part of a broader push to promote democratic resilience, writes Steven Feldstein, a senior fellow in Carnegie’s Democracy, Conflict, and Governance Program.

Credit: ODI

The broader lesson for Europe, particularly for countries on its eastern flank already prone to Russian influence and corruption, is that foreign interference and online disinformation are not just social media problems. Their expansion stems from a variety of sources, including old-fashioned bureaucratic disorganization and the potency of dirty money in business and politics, he adds:

The picture in Europe is sobering, but the commission has a unique opportunity to achieve a better balance between unleashing technological innovation and building a sound democratic future. Ultimately, the success of policies like the EDAP and the DSA hinge not only on whether they can cut down on polarizing online rhetoric without doing grave damage to free speech but also on whether the European Commission will also consider the broader range of digital tech issues that are challenging the cornerstones of Europe’s democracies.