The White House today issued a notice for the continuation of the national emergency with respect to Sudan with respect to UN sanctions obligations related to the conflict in Darfur, while insisting that the move “does not reflect negatively” on the improved bilateral relationship or on the performance of the civilian-led transitional government.

The White House today issued a notice for the continuation of the national emergency with respect to Sudan with respect to UN sanctions obligations related to the conflict in Darfur, while insisting that the move “does not reflect negatively” on the improved bilateral relationship or on the performance of the civilian-led transitional government.

“Although there remains more to be done, the United States applauds the dramatic progress that the civilian led transitional government has made in working toward freedom, peace, and justice for the Sudanese people,” the statement adds.

Sudan’s transition is in deep trouble, says a leading analyst. Almost eighteen months after a popular revolution ousted President Omar al-Bashir, Sudan’s democratic prospects are on shaky ground, International Crisis Group expert Jonas Horner asserts. While the Juba peace agreement signed in August and President Trump’s recent announcement that Sudan will be removed from the U.S. State Sponsors of Terrorism (SST) list are welcome developments, the economic crisis and societal frustrations persist in the absence of substantial support from the international community. A lack of buy-in is endangering initial signs of progress and the way political alignments are currently shifting in the capital is cause for concern.

NDI

When the army tossed out Mr Bashir last year, the UAE was happy to see him go, The Economist adds. It is not terribly eager to see democracy emerge in Sudan, though–or any other Arab country. It helped orchestrate the coup in 2013 that toppled Egypt’s only democratic government, led by the Muslim Brotherhood, and replaced it with an authoritarian general, Abdel-Fattah al-Sisi. It has also backed a wannabe Sisi, Khalifa Haftar, in his unsuccessful quest to conquer Libya. If ties with Israel, unpopular with some in Sudan, undermine its transition to democracy, the UAE won’t mind.

While Sovereignty Council head Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan remained tight-lipped about normalization in public, the council’s vice president, Gen. Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, better known by his nickname Hemeti, campaigned for it at gatherings all around the country, arguing that engagement with Israel was in Sudan’s best interests, adds analyst Ehud Yaari.

The main objections came from Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok, who heads a civilian cabinet created by the partnership formula reached between the military chiefs and the “Freedom and Change” political coalition. As late as September, Hamdok was still attempting to delink the Israel issue from Sudan’s U.S. terrorism designation. Yet his position softened once Washington firmly conditioned the end of sanctions on peace with Israel, he writes for The Washington Institute.

Although support behind Sudan’s push to normalize relations is fractured, maintaining transparency should be central to the government’s efforts as Sudan moves toward democratization, adds Mohamed Elshekh. A decision should be achieved through a broad coalition and consensus among political parties that is representative of the population. The Sudanese people did not take to the streets, depose their former dictator, and suffer the loss of countless lives just to be subject to backdoor deals once more, he writes for the Whitehead Journal of Diplomacy and International Relations.

Although support behind Sudan’s push to normalize relations is fractured, maintaining transparency should be central to the government’s efforts as Sudan moves toward democratization, adds Mohamed Elshekh. A decision should be achieved through a broad coalition and consensus among political parties that is representative of the population. The Sudanese people did not take to the streets, depose their former dictator, and suffer the loss of countless lives just to be subject to backdoor deals once more, he writes for the Whitehead Journal of Diplomacy and International Relations.

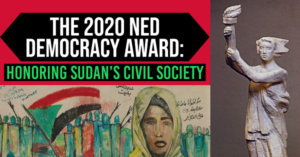

Civil society groups critical to Sudan’s revolution – the Regional Centre for Development and Training (RCDCS), the Nuba Women for Education and Development Association (NuWEDA), and the Darfur Bar Association (DBA) – were recently honored with the 2020 National Endowment for Democracy (NED) award (above), in recognition of “working tirelessly to strengthen civil society in Sudan.”