Photo Credit: U.S. Holocaust Museum

“We’ve witnessed a sharp rise in nationalist rhetoric that plays to people’s fears instead of their hopes. Institutions and reforms are being challenged… compromise and cooperation dismissed.”

Those are the words of Antony Blinken, then Deputy Assistant to the President and National Security Advisor to the Vice President, speaking ten years ago at a forum co-organized by the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) and the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

He was referring to Bosnia on the 15th anniversary of the genocide at Srebrenica. But his words seem chillingly prescient and relevant to the current upsurge of populist, illiberal and authoritarian forces, both within and beyond the established democracies.

In order to counter that resurgence, it is imperative to build strong and resilient democratic institutions at both the domestic and international levels, argues Blinken, now the Secretary of State nominee.

“The United States has European allies and Asian allies, but no institution links the Asian and European democracies,” he observed in a recent essay co-authored with Brookings analyst Robert Kagan:

As China’s Belt and Road initiative draws Asia, Europe and the Middle East closer together in ways that serve Beijing’s interests, the democracies also need a global perspective—and new institutions to forge a common strategic, economic and political vision. Why shouldn’t Germany and France work with India and Japan on strategic issues? Such an organization—call it a league of democracies or a democratic cooperative network—would not just address military security but also cybersecurity and other threats that democracies face today, from terrorism to election interference.

As China’s Belt and Road initiative draws Asia, Europe and the Middle East closer together in ways that serve Beijing’s interests, the democracies also need a global perspective—and new institutions to forge a common strategic, economic and political vision. Why shouldn’t Germany and France work with India and Japan on strategic issues? Such an organization—call it a league of democracies or a democratic cooperative network—would not just address military security but also cybersecurity and other threats that democracies face today, from terrorism to election interference.

“[A]fter World War II, when Americans stayed engaged, built strong alliances with fellow democracies, and shaped the rules, norms and institutions for relations among nations, we produced unprecedented global prosperity, democracy and security from which Americans benefited more than anyone,” they wrote in a piece originally published by The Washington Post.

The principal external threat the United States faces today is an aggressive and revisionist China—the only challenger that could potentially undermine the American way of life, argue Kori Schake, Jim Mattis, Jim Ellis, and Joe Felter. The United States’ goal, however, should not only be to deter great-power war but to seek great-power peace and cooperation in advancing shared interests. For that, the United States’ alliances and partnerships are especially crucial, they write for Foreign Affairs.

But at a recent virtual Bloomberg conference on national security, former secretary of state Henry Kissinger cautioned against building a coalition of democracies to take on Beijing, Joseph Bosco writes for The Hill.

“I think democracies should cooperate wherever their convictions allow it or dictate it,” he said. “I think a coalition aimed at a particular country is unwise, but a coalition to prevent dangers is necessary where the occasion requires.”

A proposed global summit of democracies has the potential of clarifying our understanding of global alignments—retiring the West vs. East paradigm, putting in its place a dichotomy of liberal and illiberal, free and unfree, according to one observer. According to a campaign website, the summit “will prioritize results by galvanizing significant new country commitments in three areas: (1) fighting corruption; (2) defending against authoritarianism, including election security; (3) advancing human rights in their own nations and abroad,” Shay Khatiri writes for The Bulwark:

A proposed global summit of democracies has the potential of clarifying our understanding of global alignments—retiring the West vs. East paradigm, putting in its place a dichotomy of liberal and illiberal, free and unfree, according to one observer. According to a campaign website, the summit “will prioritize results by galvanizing significant new country commitments in three areas: (1) fighting corruption; (2) defending against authoritarianism, including election security; (3) advancing human rights in their own nations and abroad,” Shay Khatiri writes for The Bulwark:

The summit will be not just an affair of governments but also their peoples. It “will include civil society organizations” that “stand on the frontlines in defense of our democracies,” and will result in a “call to action” for the private sector, including tech companies, to “make concrete pledges for how they can ensure their algorithms and platforms are not empowering the surveillance state, facilitating repression in China and elsewhere, spreading hate, spurring people to violence, and remaining susceptible to misuse,” he adds.

While enhanced collaboration between democracies may be beneficial, engagement with unsavory or autocratic regimes is often inevitable, one analyst suggests.

“The nearest that politics has to a law, in the Newtonian sense, is that democracies do not go to war with each other. From peace to active and exclusive collaboration, forswearing grubbier allies, is some leap, though,” The FT’s Janan Ganesh insists. “The 1956 Suez crisis implied, and more recent tiffs between the US and its allies confirm, that having free elections in common is not a strong enough basis for a ‘league’. The urge to make one, to seek safety in numbers, seems to come from a bleakness about the rise of unfreedom.”

In any case, the U.S. has much work to do to repair frayed alliances, even with long-term allies.

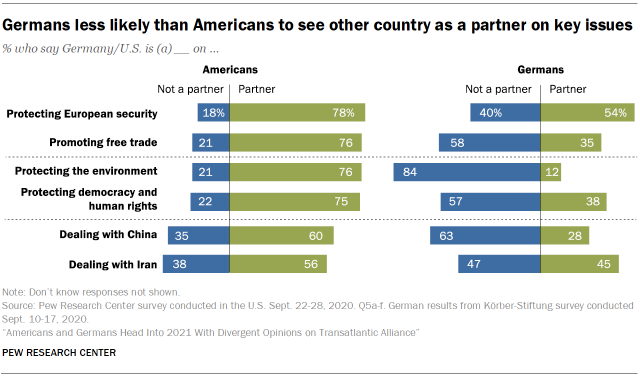

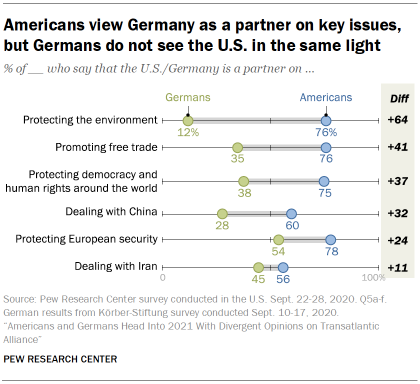

Americans tend to see Germany as a partner on key issues, such as protecting the environment, promoting free trade, democracy and human rights, ensuring European security, and dealing with China and Iran. But few Germans do, according to Pew Center Research (above):

When asked about partnering on key issues, a majority of Germans say that the U.S. is not a partner on nearly every issue tested. Fewer than four-in-ten say that the U.S. is a partner on dealing with China, promoting free trade, protecting democracy and human rights, and protecting the environment. In fact, a mere 12% of Germans say the U.S. is a partner on the environment.

A staunch advocate of international alliances, Blinken has emphasized a holistic view for countering China’s growing military, diplomatic and economic influence around the world that begins with rebuilding trust with key American allies in Asia and Europe, Roll Call reports.

“We have to start to rebuild the foundational strengths of the United States, promoting innovation, reinvigorating alliances, in partnerships with other democratic nations,” he said. “And that in turn becomes the core for collective defense and high standards of international cooperation across the whole range of policy issues.”

“The first step is actually revitalizing these alliances, revitalizing these partnerships, reasserting that America values them and that we want to be engaged in them or with them to work together to tackle these hard problems,” he told the Hudson Institute in July.

Recent developments indicate that gone are the days when dozens of senior officials at State resigned in protest over proposals to “dramatically scale back the already measly sums America spends on refugees, democracy promotion, women’s rights, and the prevention of H.I.V.,” Truman National Security Project Partner Kevin Walling writes for The Hill.

National Endowment for Democracy (NED)

Supporters expect Blinken will take a tougher stance on human rights, especially against China for its assault on Uighurs and other Muslim ethnic minorities or Hong Kong and its democracy, ABC News adds.

Expect foreign policy to become boring again, Tuft’s Daniel Drezner writes for The Post: As Graeme Wood notes in the Atlantic, Biden’s choices to date are “the equivalent of a warm cup of Ovaltine with a melatonin chaser.” He did not mean this as an insult, but rather as an acknowledgment that “they were hypercompetent public servants who tended not to make hilarious, unforced errors.”

“Srebrenica stands as a stark reminder that there are evil people prepared to kill without conscience or mercy if the world stands aside,” said Blinken, recalling the murder of 8,000 Muslim men and boys in broad daylight in Europe at a forum – “Fifteen Years Later: Forward or Backward in the Balkans?“ – co-organized by the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) and the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum to reflect on the 1995 massacre.