A majority in nine countries across the Arab world feel they are living in significantly more unequal societies today than before the Arab spring, an era of uprisings, civil wars and unsteady progress towards self-determination that commenced a decade ago, according to a Guardian-YouGov poll, the Guardian’s Michael Safi writes:

Even in Tunisia, a “success story” where democratic institutions have withstood assassinations and infighting, there was deep disillusionment. Twenty-seven per cent of those polled agreed they were better off since the revolution there, the highest among the countries surveyed. But amid stagnant economic growth and high unemployment, exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic, half of Tunisians said they were now worse off.

But a majority in several countries do not regret the protests, the survey finds (see below).

Perhaps it is ironic that despite the continuing attempts by counter-revolutionary forces to abort the Arab Spring, the hopes for democracy are still alive, notes Khalil al-Anani, a Senior Fellow at the Arab Centre for Research and Policy Studies in Washington DC:

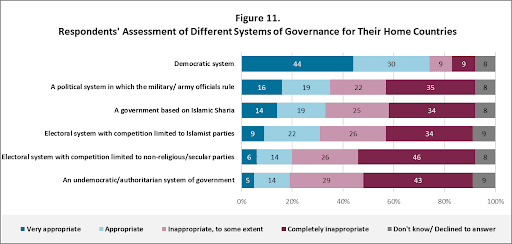

According to the 2019-2020 Arab Opinion Index, the largest annual survey in the Arab world conducted by the Arab Centre for Research and Policy Studies, about 74 percent of Arabs believe that democracy is the most appropriate system of governance for their home countries.

Arab Centre for Research and Policy Studies

Moreover, the Arab region has witnessed another wave of uprisings and revolutions over the past two years, including Sudan, Algeria, Iraq and Lebanon. Throngs of demonstrators have taken to the streets to demand economic, social and political change, Anani writes for Middle East Eye.

The Arab Spring may have shown the West that the Middle East is open to democracy and change, as one analyst attests in Foreign Policy. But the seeds of modern democracy have yet to be properly sown in the Arab world, the Economist observes:

The thirst among Arab citizens to choose their own rulers is as strong as it is elsewhere. What they need most is for independent institutions—universities, the media, civic groups, above all the courts and the mosques—to evolve without being in thrall to government. Only then can space be found for an engaged and informed citizenry. Only then are people likely to accept that political disputes can be resolved peacefully.

The pandemic is making a reboot of the Arab uprisings more likely. Europe should be prepared, argues Dr Nikki Ikani, a Research Associate in “Learning and Intelligence Use in European Foreign Policy” at King’s College London, who works on the INTEL research project which investigates the anticipation of foreign policy surprises.

Ten years after the Arab spring – Why democracy failed in the Middle East https://t.co/A6hqP7pltU

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) December 17, 2020

Jordan’s former Foreign Minister Marwan Muasher says a decade after the Arab Spring, there is still little good governance in the Arab world, as leaders fail to address popular demands for greater rights and rule of law. “The Arab world so far has largely refused to acknowledge that the old order has died,” he told VOA.

“The old tools it used — the ‘carrot’ of financial resources and ‘stick’ of security services are crumbling. These tools have to be replaced by inclusive decision-making by moving from patronage to productivity,” said Muasher, now a vice president at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and author of The Second Arab Awakening. “By educational systems that prepare people to deal with the complexities of life and by nurturing pluralism, respecting the diversity of the Arab world and understanding that it should be (a) source of strength and not weakness.”

The Arab Spring exposed the innate fragility of many of the affected states, adds former Israeli foreign minister Shlomo Ben-Ami, Vice President of the Toledo International Center for Peace. While some leaders managed to hold onto power, and some repressive military apparatuses remain robust, weak legitimacy, often based on rigged elections, leave them highly vulnerable, especially in the face of tribalist and Islamist sentiment. (It is no coincidence that the Arab monarchies – Morocco, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia – which derive their legitimacy largely from religious sources, fared much better than the pseudo-presidential republics), he writes for Project Syndicate.

The Arab Spring exposed the innate fragility of many of the affected states, adds former Israeli foreign minister Shlomo Ben-Ami, Vice President of the Toledo International Center for Peace. While some leaders managed to hold onto power, and some repressive military apparatuses remain robust, weak legitimacy, often based on rigged elections, leave them highly vulnerable, especially in the face of tribalist and Islamist sentiment. (It is no coincidence that the Arab monarchies – Morocco, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia – which derive their legitimacy largely from religious sources, fared much better than the pseudo-presidential republics), he writes for Project Syndicate.

State collapse

As protest movements were brutally repressed and sectarian hatred ignited, jihadists — in Syria and elsewhere — found fertile ground, AFP reports.

As protest movements were brutally repressed and sectarian hatred ignited, jihadists — in Syria and elsewhere — found fertile ground, AFP reports.

“It didn’t take long for the protesters’ non-violent ethos to flicker out in the battle zones of Libya, Syria, and Yemen,” author and journalist Robert F. Worth writes in A Rage for Order. “Under the convenient cover of street protests — where they could travel without being recognised — the jihadists were suddenly watching the collapse of the state in all three countries.”

Massive and sustained popular uprisings in Sudan, Algeria, Iraq, and Lebanon have shown that the Arab world is far from finished with the question of democracy, says a leading analyst.

It is reasonable to expect more turmoil in the Arab region as countries start down the difficult road from rentier-based authoritarianism toward productive economies and political systems accountable to citizens, the Carnegie Endowment’s Michele Dunne observes.

It is reasonable to expect more turmoil in the Arab region as countries start down the difficult road from rentier-based authoritarianism toward productive economies and political systems accountable to citizens, the Carnegie Endowment’s Michele Dunne observes.

Governance in Arab states a decade from now will probably involve a patchwork of systems, with nascent forms of democracy having the best chance of taking root in those countries where levels of human development are relatively high, states are less able to rely on hydrocarbon rents, and intervention by regional or outside frenemies is less prevalent. Meanwhile the social forces desiring change and those resisting it will compete to see who can learn more quickly and put that learning to better effect, she wrote for the NED’s Journal of Democracy. RTWT

For the 10th anniversary of the beginning of the Tunisian revolution, @POMED asked nine Tunisian colleagues to reflect on what the past decade has yielded, answering the question: “What does this anniversary mean to you?”

This is key. The youngest generation, 18-24, were the most positive about the revolutions – no room for nostalgia if you can’t remember the past. But across the region, a majority in five countries said they did not regret the wave of freedom movements pic.twitter.com/9D7e1kuqVu

— michael safi (@safimichael) December 17, 2020