Have the United States’ democratic bona fides dimmed?

Have the United States’ democratic bona fides dimmed?

In China, the Capitol siege has provided a boost to the ruling Communist Party, which has long warned citizens that democracy is a recipe for chaos, the Post reports.

“Chinese state media is already proclaiming the riots in Washington as the failure of democracy,” said Deng Yuwen, a former editor of a party newspaper. “This is a huge help to the Communist Party’s legitimacy.”

But democracy advocates have rejected Beijing’s efforts to equate the attack on the U.S. Capitol with 2019 protests at Hong Kong’s Legislative Council.

The linking of the two incidents has raised an uproar on social media, with residents and reporters in Hong Kong angrily insisting the incidents are not comparable. Self-exiled Hong Kong activist Nathan Law, who graduated from Yale University, tweeted about such comparisons, VOA reports:

“It’s the WRONG comparison. Several scenes on 1st July 2019, one of the monumental days of the protest movement, can help you tell the differences,” he said.

“The protesters had a very clear understanding of what they were targeting, they only damaged the symbols representing the authoritarian regime.” Law added, “The protesters who entered the building were civilized and well-mannered. They were fighting for a better society and social justice. They were demanding an unelected government implement a fair and open electoral system.”

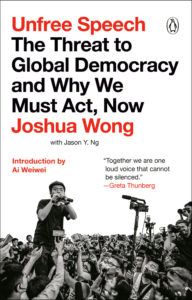

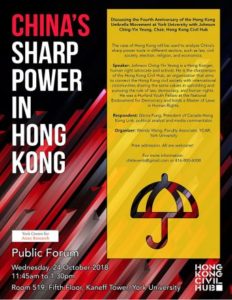

Since China implemented the National Security Law in July, Hong Kong’s pro-democracy figures have faced repeated arrests. Prominent activists Joshua Wong (author of Unfree Speech, above), Agnes Chow and Ivan Lam were sentenced to prison over illegal assembly charges. Media mogul Jimmy Lai is behind bars, charged with colluding with foreign entities, argues Maggie Shum, research associate at the Keough School of Global Affairs at the University of Notre Dame, and a former intern at the National Endowment for Democracy and Freedom House.

Since China implemented the National Security Law in July, Hong Kong’s pro-democracy figures have faced repeated arrests. Prominent activists Joshua Wong (author of Unfree Speech, above), Agnes Chow and Ivan Lam were sentenced to prison over illegal assembly charges. Media mogul Jimmy Lai is behind bars, charged with colluding with foreign entities, argues Maggie Shum, research associate at the Keough School of Global Affairs at the University of Notre Dame, and a former intern at the National Endowment for Democracy and Freedom House.

What makes the latest sweep so devastating to Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement? Here are four takeaways for the city’s political future, she writes for the Post:

- Attempting to win an election becomes subversion under the National Security Law.

The nonbinding primary election in July was an informal effort by the opposition to select their most popular candidates to compete in the September Legislative Council (LegCo) election, which Hong Kong’s pro-Beijing government then postponed to September this year. Emboldened by a landslide victory in the 2019 district council elections, the pro-democracy camp hoped to capture a majority of seats in the LegCo, which has been historically dominated by pro-Beijing factions. Such a majority would grant the opposition power to veto the government’s annual budget. More than 600,000 Hong Kongers voted peacefully in the unofficial primary as a symbol of defiance against Beijing’s tightening grip on the city…..

- Hong Kong appears to be widely purging the opposition.

Among those arrested were candidates in last summer’s primary who span the political spectrum of Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement. They include veteran lawmakers, younger and radical activists who rose to prominence during the protests, and moderate independents. Jeffrey Andrews, for instance, was the first ethnic minority candidate to advocate for marginalized communities in Hong Kong. Although most of the arrested were released on bail, with their travel documents confiscated, the message from Beijing remains clear: Any association with the opposition could result in suppression.

Among those arrested were candidates in last summer’s primary who span the political spectrum of Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement. They include veteran lawmakers, younger and radical activists who rose to prominence during the protests, and moderate independents. Jeffrey Andrews, for instance, was the first ethnic minority candidate to advocate for marginalized communities in Hong Kong. Although most of the arrested were released on bail, with their travel documents confiscated, the message from Beijing remains clear: Any association with the opposition could result in suppression.

- The arrests may dampen pro-democracy activism.

Police also arrested those who helped organize the primary, including professor Benny Tai, former lawmaker Au Nok-hin and Andrew Chiu Ka-yin, the convener of Power for Democracy, an advocacy group that coordinates the pro-democracy camp’s electoral campaigns….What about the 600,000 Hong Kongers who turned out to vote in the primary? Despite Secretary Lee’s claims that voters were not targeted in Wednesday’s operation, the fear of prosecution by association will likely discourage new generations from becoming more politically active. A number of civic groups are disbanding and deleting their records for fear of a new wave of crackdowns, and pro-democracy media outlets also report increasing intimidation by police.

- The rules of political engagement have tightened.

For authoritarian regimes that permit some level of political competition, elections are points of vulnerability that may weaken the regime — and, in Hong Kong’s case, potentially erode Beijing’s political control over the city. But Beijing and the Hong Kong government miscalculated the broad support for the pro-democracy movement and suffered an embarrassing defeat at the district council elections in 2019. Since then, Chinese and Hong Kong officials have intensified efforts to manage politics on the street and in elections. The covid-19 pandemic along with the National Security Law, for instance, have stifled the large protests in the streets.