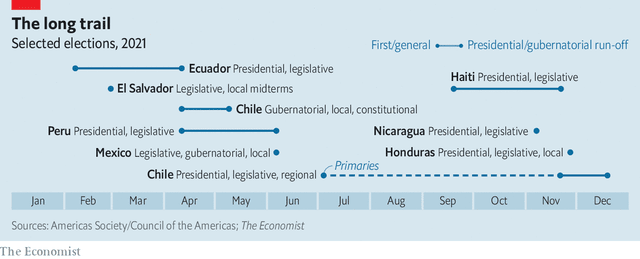

When Ecuadoreans choose a new president and legislature on February 7th, they will begin a busy political year across Latin America. Chile, Haiti, Honduras, Peru and Nicaragua are due to hold national elections (see chart). Chile will elect a constitutional assembly. Argentina, El Salvador and Mexico will hold legislative and regional votes, the Economist reports:

They are a diverse bunch. Chile is a mature democracy. Ecuador and Peru are rowdier ones and Haiti is dysfunctional. Nicaragua’s strongman, Daniel Ortega, has stamped out democracy. Nayib Bukele may be doing so in El Salvador. Chile and Peru have managed their economies well. Argentina and Ecuador have recently defaulted on their debts.

Democracy in Latin America is likely to come under increasing pressure in the coming months and years. In countries where it is already compromised, it could break down completely, argues Oliver Stuenkel, Associate Professor of International Relations at the Getulio Vargas Foundation in São Paulo, Brazil. Greater U.S. support for vulnerable civil society groups, judges, and journalists would help shore up democracy in the region, he writes for Foreign Affairs:

Democracy will face a particularly challenging stress test in Brazil in 2022, when Bolsonaro will stand for reelection and is widely expected to challenge the result if he loses. Bolsonaro will likely view Biden’s strong emphasis on human rights, democracy, the environment, and anticorruption efforts as a threat and may embrace a siege mentality in response, exploiting long-standing public concern about U.S. meddling. While U.S. policymakers must be very careful not to be seen as lecturing Latin American leaders or interfering in the region’s domestic affairs, the calculus of aspiring authoritarians, such as Bolsonaro and Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele, will inevitably change if they face a U.S. administration ready to condemn violations of democracy overseas.

The Covid pandemic has exposed a range of governance deficiencies which “produced widespread disillusionment with the region’s governments, both democratic and authoritarian, and unexpectedly powerful social protests such as those in Ecuador, Chile, and Colombia in fall 2019,” notes analyst Evan Ellis.

The Covid pandemic has exposed a range of governance deficiencies which “produced widespread disillusionment with the region’s governments, both democratic and authoritarian, and unexpectedly powerful social protests such as those in Ecuador, Chile, and Colombia in fall 2019,” notes analyst Evan Ellis.

In both its message and policies, the Biden team will be challenged to balance complex and sometimes conflicting imperatives in U.S. domestic politics, in the region, and in the broader world, he writes for CSIS:

- While exploring new opportunities for engagement with the Latin American left, the Biden administration should avoid giving corrupt anti-democratic regimes, such as those of Maduro in Venezuela or Ortega in Nicaragua, the perception that they can hold onto power and reintegrate themselves into the region without restoring democracy and desisting from criminal behavior and human rights abuses.

- In emphasizing U.S. values such as political tolerance and respect for human rights, the Biden team must signal to conservatives in the region that is also attentive that some leftist groups may abuse freedom of expression and exploit grassroots protest movements to subvert and destabilize these governments.

- The Biden team should also reassure Latin American security forces that, while the United States demands they execute their duties in a fashion consistent with internationally recognized principles of human rights and their own constitutional and legal frameworks, it will not presume guilt on the basis of accusations alone or use this as a reason to fully disengage from combating crime and insecurity in the region.

- With respect to actors such as China, Russia, and Iran, the Biden team should clarify that it will push back on non-transparent, corrupt, or predatory forms of engagement, particularly in sensitive sectors such as telecommunications infrastructure, that threaten the ability of Latin American partners to make private, autonomous decisions about foreign policy…..

The future of Cuba’s engagement with the region has taken on increased importance, especially considering the Biden administration’s commitment to re-engage with the island state, Ellis adds. Indeed, beyond the issue of U.S. policy toward Cuba itself, the latter’s contribution to the survival of the Maduro regime in Venezuela and the contribution of Venezuela’s oil and other resources to Cuba’s survival raise the possibility of new initiatives involving Cuba to secure democratic transition in Venezuela, he tells FPRI’s John Nagl.

The future of Cuba’s engagement with the region has taken on increased importance, especially considering the Biden administration’s commitment to re-engage with the island state, Ellis adds. Indeed, beyond the issue of U.S. policy toward Cuba itself, the latter’s contribution to the survival of the Maduro regime in Venezuela and the contribution of Venezuela’s oil and other resources to Cuba’s survival raise the possibility of new initiatives involving Cuba to secure democratic transition in Venezuela, he tells FPRI’s John Nagl.

In the messiness there are also reasons for hope. Outside Central America there are few budding strongmen. Elections channel discontent, which is better than violent protest, the Economist adds. They offer “somewhat of a safety valve”, says Christopher Sabatini of Chatham House, a former Latin America program officer at the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), the Washington-based democracy assistance group. But massive problems await the winners. Honeymoons will be short.