Freedom House

Moldova could be led for the first time by two women after President Maia Sandu on Friday appointed a close political partner Natalia Gavrilita as Prime Minister-designate, Balkan Insight reports.

Sandu founded the Action and Solidarity Party (PAS) in May 2016. She was PAS party president until December 2020 when she resigned from the position after winning the presidential elections.

With her hands on all the levers of power, Ms Sandu now has a unique opportunity, the Economist observes. Her government must now clean up the judiciary, she says. Vadim Pistrinciuc, a reformist former MP, agrees but adds that if the government moves too slowly, a historic chance to break the link between the judges, the oligarchs and the media they control will be lost. They will regroup fast, he says. “Unless their power is smashed within six months, they will never leave.”

With her hands on all the levers of power, Ms Sandu now has a unique opportunity, the Economist observes. Her government must now clean up the judiciary, she says. Vadim Pistrinciuc, a reformist former MP, agrees but adds that if the government moves too slowly, a historic chance to break the link between the judges, the oligarchs and the media they control will be lost. They will regroup fast, he says. “Unless their power is smashed within six months, they will never leave.”

Moldovan prosecutors have detained former defense minister Alexandru Pinzari in connection with a case of alleged forgery of documents, abuse of power and drug trafficking, BIRN adds.

Pinzari is a suspect in a case filed against Dorin Damir, fugitive oligarch Vladimir Plahotniuc’s godson, about fake identities, forging official documents and drug trafficking allegations. Damir was head of the Moldovan Mixed Martial Arts Federation, and his name appeared in several Moldovan journalistic investigations about anabolic steroid trafficking.

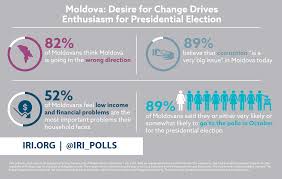

According to Transparency International, Moldova is the third-most-corrupt nation in Europe, after Ukraine and Russia; not surprisingly, it is also the least developed, the Post adds. Its population has fallen by more than a quarter in 30 years as people have fled its dysfunction.

How does the fight for liberal democracy align with the need for transparency and accountability in business and politics? analyst Iulia-Sabina Joja asked President Sandu. “The magnitude of corruption in Moldova transformed it into a threat to our national security,” she observed:

How does the fight for liberal democracy align with the need for transparency and accountability in business and politics? analyst Iulia-Sabina Joja asked President Sandu. “The magnitude of corruption in Moldova transformed it into a threat to our national security,” she observed:

After the dismantling of the USSR, we had to build the state from scratch. We failed in such short time to build strong, resilient, and accountable institutions, while interest groups have used the weakness of the state to capture it and subordinate it to their own benefits. We emulated many of the best practices of Western countries and have to some degree built a strong framework that ensures the independence of public institutions. The individuals in these institutions, however, misuse this independence to promote their own personal interests.

“To work toward genuine liberal democracy, we have to rethink how to make these institutions transparent and accountable to citizens, key features that should have come in before we granted them independence,” Sandu told American Purpose. RTWT

Sandu managed to maintain a clean political record despite her place in the Filat government, notes Anda Bologa, a Denton Fellow with the Transatlantic Leadership program at the Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA), a partner of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). The true challenge now is to form an administration of experts and politicians with equal credibility. Furthermore, success in governance and maintaining public support – while necessary – is insufficient. PAS needs a plausible strategy to answer the most acute public needs: rehabilitating the healthcare and educational systems, improving socio-economic conditions, fighting corruption, and reversing the flow of mass emigration.

This year’s snap elections in Moldova eliminated several political groups that were brought to power by fugitive oligarch Vladimir Plahotniuc, adds Giessen University researcher Denis Cenusa, an associate expert at Moldova’s “Expert-Grup” think tank and a contributor at IPN News Agency in Moldova since 2015. President Sandu’s party now enjoys a majority in parliament. This will enable the government to lift the immunity of any problematic parliamentarians whenever requested by the prosecutor general, he writes for New Eastern Europe. RTWT

This year’s snap elections in Moldova eliminated several political groups that were brought to power by fugitive oligarch Vladimir Plahotniuc, adds Giessen University researcher Denis Cenusa, an associate expert at Moldova’s “Expert-Grup” think tank and a contributor at IPN News Agency in Moldova since 2015. President Sandu’s party now enjoys a majority in parliament. This will enable the government to lift the immunity of any problematic parliamentarians whenever requested by the prosecutor general, he writes for New Eastern Europe. RTWT

For years, Plahotniuc effectively steered Moldova’s economic development, transforming it into a key linchpin of post-Soviet kleptocracy, the New Republic’s Casey Michael observed.

“In a way, it will draw the line on 30 years of post-Soviet blindness — years of poverty and exodus, of endless thieves, of violation of human dignity, of disregard for national values,” commentator Vitalie Ciobanu wrote of the elections in a commentary for RFE/RL’s Moldovan Service. “It is time to remember the founding acts of the Republic of Moldova, a state that wanted the expression of freedom of its citizens but ended up with a kleptocracy.”

Moldova is one of a number of Eurasian states where distinctions between public and private sectors, licit and illicit actors hardly apply, notes Carnegie analyst Sarah Chayes. Ruling kleptocratic networks harness levers of government power to the purpose of maximizing gains or ensuring discipline. Other elements of state function are disabled, meaning capacity deficits may be deliberate, she writes.

Moldova is one of a number of Eurasian states where distinctions between public and private sectors, licit and illicit actors hardly apply, notes Carnegie analyst Sarah Chayes. Ruling kleptocratic networks harness levers of government power to the purpose of maximizing gains or ensuring discipline. Other elements of state function are disabled, meaning capacity deficits may be deliberate, she writes.

NDI has been monitoring the dynamic online political environment in Moldova in the aftermath of Sandu’s victory in the November 2020 presidential elections. The NDI/Moldova team utilized CrowdTangle to observe and analyze content relating to political news and democratic trends within the country. Maia Sandu’s account was consistently the most popular account monitored in terms of engagement, shares, and comments. RTWT

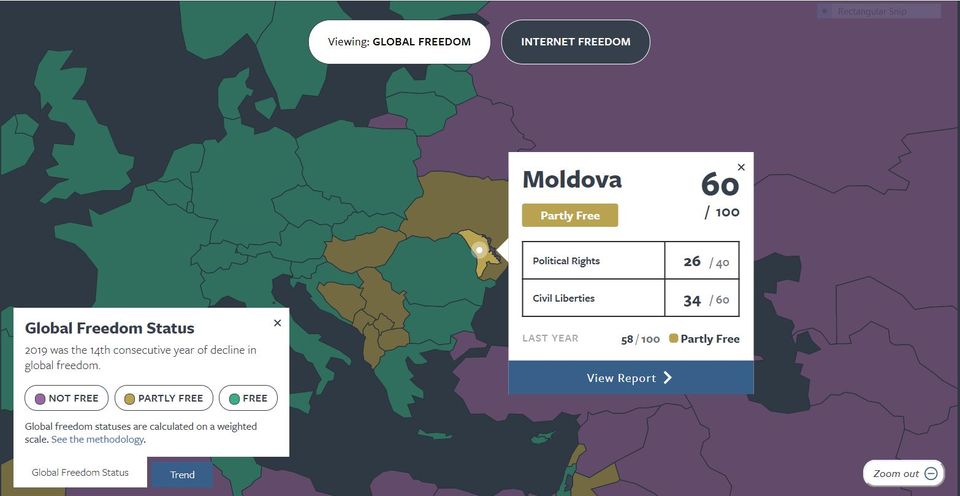

With Sandu’s victory, civil society in Moldova has high expectations that Moldova’s democratic reform efforts will finally be realized, said Gina S. Lentine, Senior Program Officer for Europe and Eurasia at Freedom House. Many were disappointed in 2019 after Sandu’s bloc formed a short-lived coalition government with the Socialists.