Credit: Carnegie

US President Joe Biden made it an early theme of his term in office, that democracy is under attack. “We’re at an inflection point,” he told an audience in Germany in February. “We must demonstrate that democracy can still deliver for our people in this changed world. That, in my view, is our galvanizing mission,” notes CNN’s Nic Robertson.

But how to deliver on that mission is something that has yet to be mastered, he adds. Biden promised a “summit of democracies” “early” in his presidency, it is due to take place next month, although details are sketchy.

The forthcoming summit cannot be merely symbolic or aspirational, argue Freedom House president Michael J. Abramowitz and David J. Kramer, a former assistant secretary of state for democracy, human rights and labor. It should not serve merely as a photo op for leaders, nor should it be a forum for empty speeches. The world desperately needs bold, tangible action from the community of democratic nations.

Screengrab

To ensure that attendees depart the virtual forum on Dec. 10 motivated and equipped to take on the growing authoritarian threat, the White House should ensure that at least three things happen at the summit, they write for The Washington Post:

- First, representatives of civil society, independent media and social movements — especially from countries not invited to attend officially — should have a privileged opportunity to speak directly to attending governments. President Biden himself should host a meeting with human rights defenders and pro–democracy activists from around the world, drawing attention to the brave individuals who continue to insist on their rights against heavy odds in Hong Kong, Belarus, Cuba, Sudan and many other places.

- Second, every attending country, led by the United States, should pledge support — financial as well as political — for the millions of courageous people around the world struggling against authoritarianism every day. … U.S. Agency for International Development administrator Samantha Power demonstrated what this might look like when she announced a new fund to support journalists facing frivolous lawsuits — often brought by cronies of authoritarian leaders — that are aimed at silencing them and thwarting accountability.

- Third, the leaders gathered by the Biden administration should issue a joint declaration with two clear messages:

- The first is to reaffirm their commitment to democratic institutions, free and fair elections, protection of minority groups and respect for civil society.

- Equally important is a statement of determination to fight authoritarian power grabs — the coups, the arrests of human rights activists, the breakdown of the rule of law and independent media, the transnational efforts to target dissidents living in democracies and interference in our elections.

Identifying the participants for such a major diplomatic gathering is a complicated process, and settling on the final summit list was more a product of bureaucratic and interagency sausage making than anything more sublime, adds Steven Feldstein, a senior fellow in Carnegie’s Democracy, Conflict, and Governance Program. What considerations were at play?

Identifying the participants for such a major diplomatic gathering is a complicated process, and settling on the final summit list was more a product of bureaucratic and interagency sausage making than anything more sublime, adds Steven Feldstein, a senior fellow in Carnegie’s Democracy, Conflict, and Governance Program. What considerations were at play?

- First, regional dynamics played a big role. Take the Middle East. Looking strictly at the democracy index numbers, the only two countries that could plausibly make a bid for participation are Israel and Tunisia. Unfortunately, Tunisia is experiencing a slow-motion coup, and the optics of having Israel attend as the sole representative from the Middle East was a nonstarter. In that context, enter Iraq—just democratic enough to score an invite, but nobody’s idea of enlightened leadership.

- Second, broader U.S. strategic interests also mattered. Pakistan, the Philippines, and Ukraine are all flawed democracies with endemic corruption and rule of law abuses. Yet they are important partners of the United States—whether to counterbalance Chinese influence (Philippines), withstand Russian encroachment (Ukraine), or assist with counterterrorism (Pakistan). Undoubtedly, the State Department’s relevant regional bureaus made the case on those grounds.

- Finally, something akin to a democratic do-no-harm test played a role in certain cases. For example, the administration’s exclusion of Hungary and Turkey may have been based on Biden’s reluctance to do anything to help the reelection chances of Hungarian Prime Minister Victor Orbán or Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

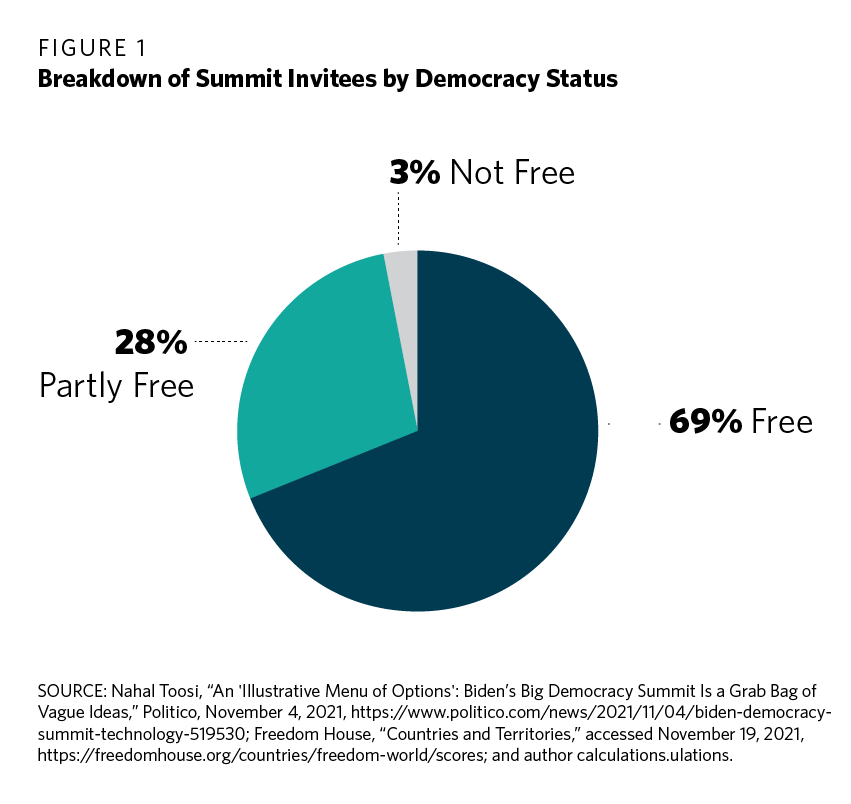

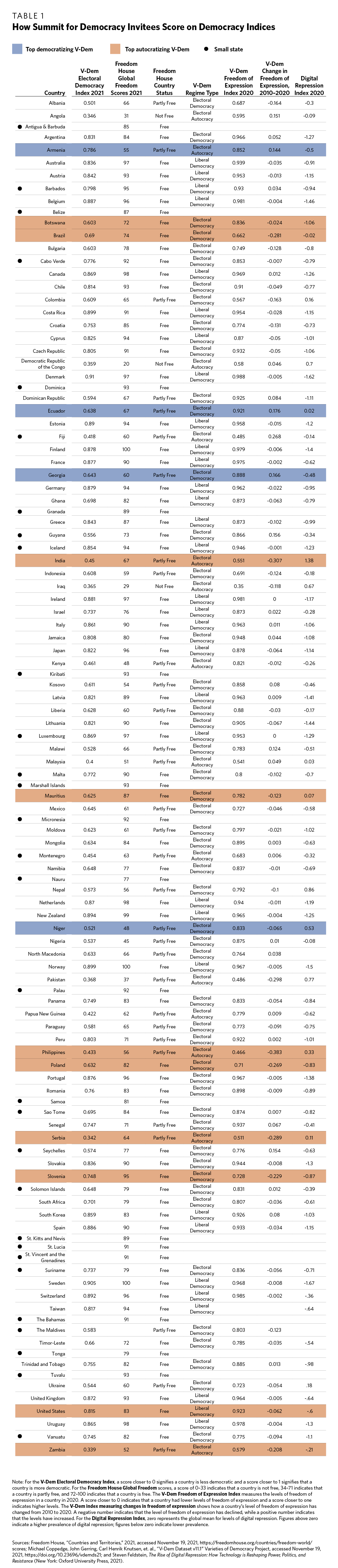

The current mix of invitees to the summit includes liberal democracies, weaker democracies, and several states with authoritarian characteristics (such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Pakistan), Feldstein observes. Rather than limit participation to a core group of committed democracies, Biden’s team opted for a big tent approach (see table 1 above). The majority of invitees—seventy-seven countries—rank as “free” or fully democratic, according to Freedom House’s 2021 report. Another thirty-one invitees rank as “partly free.” Finally, three countries fall into the “not free” camp (see figure 1 below).

The current mix of invitees to the summit includes liberal democracies, weaker democracies, and several states with authoritarian characteristics (such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Pakistan), Feldstein observes. Rather than limit participation to a core group of committed democracies, Biden’s team opted for a big tent approach (see table 1 above). The majority of invitees—seventy-seven countries—rank as “free” or fully democratic, according to Freedom House’s 2021 report. Another thirty-one invitees rank as “partly free.” Finally, three countries fall into the “not free” camp (see figure 1 below).

The Biden administration has decided to err on the side of inclusiveness, as several states guilty of undermining democracy (Poland, the Philippines, India) have found themselves on the invitation list to the summit, notes J. Brian Atwood, a visiting scholar at Brown University’s Watson Institute. It is an approach borne out by the experience of the National Democratic Institute (NDI) which, funded largely by the U.S. Agency for International Development and the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), has taken its cue from democrats on the ground, he writes for The Hill.

History suggests that democracies’ timidity in the face of authoritarian resurgence only invites catastrophe, according to a new book.

Colin Kahl and Thomas Wright’s Aftershocks: Pandemic Politics and the End of the Old International Order (St. Martin’s Press, 2021) suggests that the “failure of democratic powers” to stand together against their common challenges was a central precipitant of World War II, notes Andrew Ehrhardt, an Ernest May fellow at Harvard’s Kennedy School.

Colin Kahl and Thomas Wright’s Aftershocks: Pandemic Politics and the End of the Old International Order (St. Martin’s Press, 2021) suggests that the “failure of democratic powers” to stand together against their common challenges was a central precipitant of World War II, notes Andrew Ehrhardt, an Ernest May fellow at Harvard’s Kennedy School.

It is this basic historical judgment — that the United States missed an opportunity to unite democratic partners which could have laid the basis for larger ordering systems — which serves as a main organizing principle in both their assessment and treatment of the current problem, he writes for War On The Rocks:

[Kahl and Wright’s] approach appears to rest a belief that by combining with other like-minded countries, the United States can create a wagon to which other countries might hitch, with the end result being a modern system led by, and working in the interests of, the United States. This represents what scholars like Stewart Patrick have dubbed “coalition” or “club” approaches to ordering on an international scale. It is no doubt a reasonable and logical suggestion, and the potential strategic benefits seem obvious. This “build it and they will come” mentality in part underpinned the early ideas behind the League of Nations and later, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade.

But the process of ordering can, in many ways, shape the nature of order itself. More exclusive and more democratic groupings — aside from the perils of creating “measures” of democracy — can have the unintended consequence of driving neutral or adversarial governments away, adds Ehrhardt. In an age of increased suspicion among non-Western powers as to the purpose that existing international organizations play, health and security systems based on this view may well lead to the very arrangements they initially sought to avoid. RTWT

Credit: Carnegie