The Kremlin’s persecution of Memorial, Russia’s venerable human rights group, is typical of authoritarian attempts to exploit and distort the past to give legitimacy to violence, says Anne Applebaum, a fellow at the SNF Agora Institute at Johns Hopkins University, and the author of Twilight of Democracy: The Seductive Lure of Authoritarianism.

The Kremlin’s persecution of Memorial, Russia’s venerable human rights group, is typical of authoritarian attempts to exploit and distort the past to give legitimacy to violence, says Anne Applebaum, a fellow at the SNF Agora Institute at Johns Hopkins University, and the author of Twilight of Democracy: The Seductive Lure of Authoritarianism.

One of the group’s other founders, the late Arseny Roginsky, began collecting the names of Stalin’s victims back in the 1970s, when doing so was still illegal. This was an act of faith, she writes for The Atlantic:

One of the group’s other founders, the late Arseny Roginsky, began collecting the names of Stalin’s victims back in the 1970s, when doing so was still illegal. This was an act of faith, she writes for The Atlantic:

“I had to assume that history would outlast stupidity and cruelty,” he told David Remnick, who quotes him in his book Lenin’s Tomb. Roginsky went to jail for his efforts. But in the years following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Memorial ceased to be a dissident organization. Historians from Memorial often worked in tandem with state archivists. They used newly available Soviet sources to produce an astonishing array of books and document collections. In 2000, they produced the first complete list of the Soviet Gulag camps, with a brief history of each one; in 2016, this material became an interactive online map. Over time, Memorial created a list of more than 3 million victims of Stalinism, and eventually made that available online too.

In a letter to the General Prosecutor of the Russian Federation this week (above), the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, Dunja Mijatović, expressed her concerns over the liquidation proceedings against International Memorial and Human Rights Centre Memorial – based on the legislation governing the activities of non-commercial groups receiving foreign funding, known as the “foreign agents” law.

Credit: Human Rights House Foundation

Twelve years after the murder of Natalia Estemirova (right), head of Memorial’s office in Grozny, the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg ruled that the investigation into her murder had not been effective, adds Ane Tusvik Bonde, Senior Advisor at Human Rights House Foundation. The Court decided the evidence provided was not sufficient to prove that the Russian authorities were behind her kidnapping and murder.

“[Russian] state prosecutors are taking action to shut down Memorial, a step that signifies a dual assault on modern Russian civil society and on the nation’s wider struggle for historical memory and justice,” the FT’s Tony Barber writes. “Putin’s crackdown on dissent is inextricable from a desire to control Russia’s past.”

A longstanding pillar of Russian civil society, Memorial, an NGO founded to preserve historical memory of atrocities committed under the Soviet Union, is under intense new pressure as authorities work to shut it down, the Atlantic Council’s Doug Klain writes for The Hill.

Although Memorial was originally conceived as an educational organization, its members quickly realized that they couldn’t just study the past and ignore the political realities of the present, Meduza reports.

Although Memorial was originally conceived as an educational organization, its members quickly realized that they couldn’t just study the past and ignore the political realities of the present, Meduza reports.

“Under Gorbachev, those who were imprisoned on obvious political charges began to be released, but there were still ‘borderline prisoners.’ Some, like today, were prosecuted for fabricated felony offenses,” human rights activist and Memorial employee Oleg Orlov tells Meduza. “We started to deal with these political prisoners, collating lists, appealing to the prosecutor’s office, conducting pickets — this was Memorial’s first human rights track.”

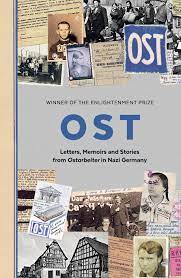

In 1989, Green Party members of the German Bundestag declared Ostarbeiter – the slave labourers taken from the occupied Soviet territories in the east to work in the Reich – to be “forgotten victims of National Socialism”, notes analyst Bryan Karetnyk. Hoping to lay the groundwork for compensatory legislation, deputies turned to the director of the then recently established Russian civil rights organization Memorial with a few basic but essential questions. How many of these “eastern workers” had there been? How many of them were still alive? And what happened to them after their return to the Soviet Union? Definitive answers were impossible to obtain, he writes for the Times Literary Supplement:

Not only had the Ostarbeiter’s forced servitude been viewed as tantamount to treason by Stalin and his successors, but it also ran counter to the carefully curated master narrative of patriotic wartime heroism, so much so that practically all record of it had been expunged from official histories. Memorial set out to change that, collecting hundreds of thousands of letters, documents and photographs over the subsequent decades, and conducting hundreds of hours’ worth of interviews with survivors.

Not only had the Ostarbeiter’s forced servitude been viewed as tantamount to treason by Stalin and his successors, but it also ran counter to the carefully curated master narrative of patriotic wartime heroism, so much so that practically all record of it had been expunged from official histories. Memorial set out to change that, collecting hundreds of thousands of letters, documents and photographs over the subsequent decades, and conducting hundreds of hours’ worth of interviews with survivors.

OST: Letters, memoirs and stories from Ostarbeiter in Nazi Germany, edited by Alena Kozlova, Nikolai Mikhailov, Irina Ostrovskaya and Irina Scherbakova, is the fruit of that endeavour, and the first major work in English to tell the Ostarbeiter’s story, he adds. RTWT

Dictators distort the past because they want to use it. Putin certainly wants to use the past to stay in power. If Russians are nostalgic for their old dictatorship, then they have less reason to push back against the new one, adds Applebaum, a board member of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED):

He may also want to use the past to give legitimacy to violence—Russians who have no awareness of what Moscow did to Ukraine in the past will feel no sense of guilt about repeating old patterns of aggression. History does contain lessons, and here is one of them: If Putin plans to turn his falsely heroic vision of Russia’s past into a justification for another war in the present, he won’t be the first autocrat to do so.

“Dictators distort the past because they want to use it: to stay in power, to bully opponents, to persuade people to commit acts of mass violence,” @NEDemocracy board member @anneapplebaum writes for @TheAtlantic https://t.co/jleXElv3Mn

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) December 8, 2021