Americans overwhelmingly view China as a “competitor” or an “enemy” to the United States, rather than a “partner.” And it appears that most U.S. adults do not think that their country is winning the competition for geopolitical influence, according to a recent Pew Research Center survey.

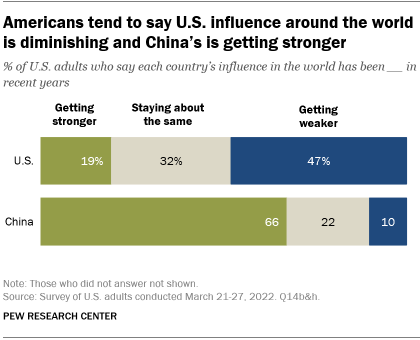

Nearly half of Americans (47%) say that the United States’ influence in the world has been getting weaker in recent years, Pew’s Aidan Connaughton writes:

Only about one-in-five say U.S. influence has been getting stronger, while 32% say U.S. influence has been staying about the same. This is in stark contrast with views of China: Two-thirds of U.S. adults say that the country’s influence has been getting stronger in recent years. Roughly one-in-five Americans say China’s global influence is holding steady, and only one-in-ten say China’s influence has been weakening.

Human rights in Hong Kong have deteriorated rapidly since Beijing’s crackdown after the pro-democracy protests of 2019, according the new Human Rights Measurement Initiative (HRMI) survey, which now ranks Hong Kong close to Saudi Arabia and Venezuela, both near last-place China.

Human rights in Hong Kong have deteriorated rapidly since Beijing’s crackdown after the pro-democracy protests of 2019, according the new Human Rights Measurement Initiative (HRMI) survey, which now ranks Hong Kong close to Saudi Arabia and Venezuela, both near last-place China.

Chung Kim-wah, honorary director of Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute, told VOA in a phone interview that survey data show that civil society in Hong Kong has shrunk, and freedom of speech and assembly has been suppressed since the imposition of the Hong Kong version of China’s National Security Law in 2020.

HK activist Claudia Mo had been warning of China’s growing authoritarianism towards the territory for years, The FT’s Primrose Riordan and Chan Ho-him write:

In 2016, after Beijing took the unprecedented step of banning two elected politicians from taking their seats in the Hong Kong legislature, she wrote it could be “the beginning of the end . . . Today Beijing talks about anti-independence, tomorrow it talks about anti-self-determination and the day after it can talk about anti-democracy altogether.” Mo has a sense of humour and honesty that have made her a beloved figure among democracy supporters. Some refer to her in Cantonese as “Auntie Mo”. While on bail, along with Instagram posts showing flowers, butterflies and sunsets, Mo posted a photo of a bottle of Citibrew beer. The label showed a woman holding an umbrella, a symbol of the democracy movement here. The beer was called “Tough Ladies IPA”.

In 2016, after Beijing took the unprecedented step of banning two elected politicians from taking their seats in the Hong Kong legislature, she wrote it could be “the beginning of the end . . . Today Beijing talks about anti-independence, tomorrow it talks about anti-self-determination and the day after it can talk about anti-democracy altogether.” Mo has a sense of humour and honesty that have made her a beloved figure among democracy supporters. Some refer to her in Cantonese as “Auntie Mo”. While on bail, along with Instagram posts showing flowers, butterflies and sunsets, Mo posted a photo of a bottle of Citibrew beer. The label showed a woman holding an umbrella, a symbol of the democracy movement here. The beer was called “Tough Ladies IPA”.

Although there is much emotion on both sides—for China, nationalism; for the United States, commitment to democracy—what makes the Taiwan issue truly nonnegotiable are the two countries’ security interests, Columbia University’s Andrew J. Nathan – a former National Endowment for Democracy (NED) board member – writes for Foreign Affairs:

China is following the dictum of the ancient strategist Sun-tzu: “To subdue the enemy without fighting is the acme of skill.” If Beijing eventually succeeds in taking Taiwan, it will fatally undermine Washington’s credibility with its Asian—and even its European—allies, challenging Australia, Japan, South Korea, and other countries to either come to terms with China or prepare to defend themselves without American help. RTWT

China is following the dictum of the ancient strategist Sun-tzu: “To subdue the enemy without fighting is the acme of skill.” If Beijing eventually succeeds in taking Taiwan, it will fatally undermine Washington’s credibility with its Asian—and even its European—allies, challenging Australia, Japan, South Korea, and other countries to either come to terms with China or prepare to defend themselves without American help. RTWT

It took almost four months for a lecture on human rights delivered by Xi Jinping at the Political Bureau of the 19th Central Committee to be published in the Qiushi, the official ideological magazine of the CCP, notes Massimo Introvigne. There is nothing new in Xi’s claim that there is no universal notion of human rights; that each country has the right to define “human rights” as it sees fit; and that the West pretends to impose under the false idea of “universal” human rights its own bourgeois notion of these rights, he writes for Bitter Winter:

What is comparatively new and interesting is the genealogy of the “excellent” Chinese notion of human rights Xi presented in the lecture. In fact, this genealogy is nothing less than extraordinary. The Chinese President mentioned six ancestors of this notion: Confucius, Mencius, Xunzi, Mozi, Marx, and Engels. The four Chinese philosophers, although none of them ever used the expression “human rights,” are mobilized through quotes attributing to them the idea that a good government should “love the people” and be “people-oriented.”

Such claims amount to “an ideological statement,” Introvigne adds, “insisting on Xi’s pet theory that there is a unified ‘Chinese traditional culture,’ whose notion is based on a reconstruction of the ideas of Confucius that does not derive from academic science but from the needs of the CCP.”

Xi’s formulation subtly undercuts the connection between rights and liberal democratic values, redefining “human rights” as access to economic opportunities, adds Maria Repnikova, an Associate Professor in the Department of Communication at Georgia State University and the author of Chinese Soft Power.

Xi’s formulation subtly undercuts the connection between rights and liberal democratic values, redefining “human rights” as access to economic opportunities, adds Maria Repnikova, an Associate Professor in the Department of Communication at Georgia State University and the author of Chinese Soft Power.

In communicating with global audiences, China’s international media outlets, such as China Daily and CGTN, follow Xi’s lead and emphasize China’s economic breakthroughs, she writes for Foreign Affairs. The CCP buttresses this kind of soft-power diplomacy with acts of material generosity. Earlier this year, for instance, Xi pledged $500 million to support development objectives in Central Asian countries, including improvements in agriculture and public health.

Chinese soft power initiatives are more dynamic in the Global South where we see more active experimentation with localizing production and marketing, as well as more potential in shaping public opinion in the absence of significant competition from the West, Repnikova adds. For instance, there is a major uptick in scholarships and trainings for students and elites from the African continent, but also from other regions in the Global South, including Latin America and Southeast Asia.

Xi Jinping Explains the CCP Theory of “Human Rights” with Marx and Confucius https://t.co/AioplDrdb2

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) June 24, 2022