I’ve often wondered, what does it take for a lone individual to stand up to a totalitarian system, and to risk it all for the right to speak and associate freely? writes David E. Hoffman (right), a contributing editor and member of the editorial board of The Washington Post.

I’ve often wondered, what does it take for a lone individual to stand up to a totalitarian system, and to risk it all for the right to speak and associate freely? writes David E. Hoffman (right), a contributing editor and member of the editorial board of The Washington Post.

We see many of them today, such as Alexei Navalny, the Russian opposition leader who has crusaded for years against corruption and abuse of power in Vladimir Putin’s Kremlin and was targeted for assassination with a military nerve agent. He survived and now sits in a harsh penal colony, unjustly sentenced to 11 years. Vladimir Kara-Murza, another opposition politician in Russia, who managed to survive two poisoning attempts, was recently detained for criticizing the war against Ukraine. According to the nongovernmental organization OVD-Info, 16,309 people in Russia have been detained for anti-war views since Putin launched the onslaught in February.

Sergei Tikhanovsky, a blogger who dared announce an election challenge to Belarus dictator Alexander Lukashenko, remains imprisoned for his political activism and was recently designated a terrorist. His wife, Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, ran for president after he was arrested in 2020 and, along with two others, was greeted by huge crowds demanding reform and democracy. Lukashenko responded by stealing the election, arresting hundreds and forcing Tikhanovskaya into exile. She now campaigns around the world to bring democracy to Belarus. According to the Belarus human rights group Viasna, there are 1,232 political prisoners in Belarus, including her husband.

Jose Daniel Ferrer. Credit: UNPACU Facebook

Jose Daniel Ferrer, leader of the Unión Patriótica de Cuba, known as UNPACU, a long-time opposition leader, has endured repeated arrests and jail sentences for his protests against the Cuban dictatorship. Lately he has been denied contact with relatives for weeks at a time. According to the legal aid group Cubalex, 1,484 people were detained for participating in the spontaneous protests of last July 11, of which 701 remain locked up.

What drives someone to fight the system – against the odds? Where do they find that kernel of

inspiration, courage and vision to protest in front of an implacable wall?

A right to rights

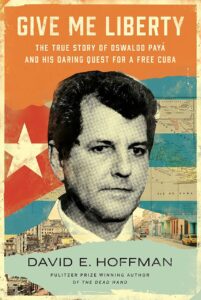

This was my starting point in the research for my new book, Give Me Liberty: The True Story of Oswaldo Payá and his Daring Quest for a Free Cuba. The biography examines the life and legacy of Payá, who devoted decades to opposing Fidel Castro’s totalitarian system. I believe Payá was the Andrei Sakharov or Václav Havel of Cuba, dedicated to the ideals of a free people and an open society.

This was my starting point in the research for my new book, Give Me Liberty: The True Story of Oswaldo Payá and his Daring Quest for a Free Cuba. The biography examines the life and legacy of Payá, who devoted decades to opposing Fidel Castro’s totalitarian system. I believe Payá was the Andrei Sakharov or Václav Havel of Cuba, dedicated to the ideals of a free people and an open society.

I discovered that what propelled Payá was a simple conviction that people have a right to rights. He saw with his own eyes how these rights were taken away in Cuba. His lessons came from the street, from the parish church, from the everyday.

In their classic work, “Totalitarian Dictatorship and Autocracy,” Carl J. Friedrich and Zbigniew

Brzezinski found that totalitarian dictatorships all possessed these levers of control: a single

party, an over-arching ideology, a system of state terror and coercion by secret police, a

monopoly over mass communications, rule over all security and military forces and central

control and command of the entire economy.

This was Fidel Castro’s aspiration. He built a Marxist dictatorship based on an overarching

ideology, a single party, a secret police, total control of communications, and the elimination of

civil society. His ambitions were to corral all of Cuba inside his revolution; as he put it, “within

the Revolution, everything; against the Revolution, nothing.” It was patterned in many ways

after Soviet Communism. Not always airtight, it was formidable.

Payá devoted a lifetime to opposing Castro’s repression. But he began with no road map. He devoted years to trial and error, attempting to figure out the best way to reach Cubans and mobilize them in a closed system.

Payá devoted a lifetime to opposing Castro’s repression. But he began with no road map. He devoted years to trial and error, attempting to figure out the best way to reach Cubans and mobilize them in a closed system.

He held a bedrock belief that the rights of every person are bestowed by God and cannot be taken away by the state. Yet they were taken away by the Castro revolution. Even something as innocent as hanging a “Feliz Navidad,” or Merry Christmas, sign on the bell tower of his church was considered subversive. Defiant, Oswaldo hung the sign anyway. He never lived in a state of liberty, but liberty lived in his mind.

As a teenager he had protested the crushing of the Prague Spring with Soviet tanks in 1968 and

was sent to Castro’s forced labor camps. He emerged from the camps unbowed and more

defiant than ever. Later, in the mid-1980s, as a member of the Catholic laity, Oswaldo urged

church to leaders stand up for human rights, but weakened by decades of repression, they

were more interested in reconciliation than confrontation.

Credit: Movimiento Cristiano Liberación Facebook

Oswaldo could not remain silent. In 1988, he and several friends created the Movimiento Cristiano Liberación, a civic and political movement, nondenominational but driven by the values of Christian democracy that had confronted fascism and communism in the twentieth century.

‘We must be the protagonists’

Around the same time, he and his friends began to publish a newsletter, Pueblo de Dios, or People of God, brimming with his ideas and commitment to truth and freedom. It was printed in several hundred copies, distributed widely every Sunday, hand-to-hand, one person to the next, well beyond Havana. The project was illicit, and that boosted its appeal among people hungry for independent information. Eventually, the church leadership demanded that Payá and his friends halt the newsletter, and they paused, for a while, but when they resumed, Payá was even more outspoken. He summoned Cubans to take matters into their own hands, a bold suggestion in a dictatorship. “We can’t be just the spectators of our own history,” he insisted. “We must be the protagonists.” On March 12, 1990, Payá and his friends were all detained for a day by Cuban state security, trying to stop publication of Pueblo de Dios.

Payá realized that he faced a difficult struggle. How to confront an implacable system—and get

others to do so?

Oswaldo Paya. Credit: NDI

He found the answer in a little-noticed provision of Cuba’s Constitution of 1940, its most democratic. The constitution provided for separation of powers among executive, legislative, and judicial branches, with an independent judiciary; declared that all Cubans were equal before the law; and prohibited discrimination of any kind. It contained strong guarantees of individual rights, including habeas corpus; freedom of thought, speech, press, conscience, assembly, and religion; inviolability of the home; and privacy of correspondence. Elections were to be based on a popular vote.

The constitution was also bulging with promises of social justice. One provision in the 1940 Constitution gave citizens the right to petition for legislation upon submission of 10,000 signatures. This provision was retained even after Castro came to power. (He broke a promise to restore the 1940 charter and eviscerated much of it.) Payá knew of this provision, and decided to use the laws of the state against itself. The provision for 10,000 signatures became his tool.

Not everything worked out at first. In July, 1991, when he was just beginning to collect signatures at his Havana home, a pro-government crowd barged in, ransacked the house and sprayed graffiti on the walls outside: “Payá, you worm,” “CIA agent,” and “Long live Fidel.” Payá pondered what had happened and how to overcome the obstacles. The movimiento “had to start from scratch several times,” he recalled.

Transition road map

By early 1992, Oswaldo concluded that his citizen initiative was missing something. It was too

vague, seeking a “national dialogue,” a referendum and a new constitution. These were not

enough.

He decided to write out a full road map for transition to a new society. He often wrote at night, sitting in bed with a board on his lap, scratching away in longhand. Maybe, he thought, this detailed plan would help persuade people to make the leap, help them see that it was possible.

He produced an extraordinary document, called Programa Transitorio, or Transition Program, brimming with sound principles and optimism. He repeatedly affirmed the right of all Cubans to decide their fate, to “practice democracy,” to assure “freedom of expression,” to protect rule of law, to enjoy “balanced dialogue, justice, freedom and accountable participation.” The plan was forty-six pages and nine chapters and ranged over economics, education, health, the military, the press, and law. Form the very start, Oswaldo insisted, “freedom of expression and association, including the establishment of political parties, unions and student organizations, will be guaranteed by law.” It would be a total reversal of the revolution.

He produced an extraordinary document, called Programa Transitorio, or Transition Program, brimming with sound principles and optimism. He repeatedly affirmed the right of all Cubans to decide their fate, to “practice democracy,” to assure “freedom of expression,” to protect rule of law, to enjoy “balanced dialogue, justice, freedom and accountable participation.” The plan was forty-six pages and nine chapters and ranged over economics, education, health, the military, the press, and law. Form the very start, Oswaldo insisted, “freedom of expression and association, including the establishment of political parties, unions and student organizations, will be guaranteed by law.” It would be a total reversal of the revolution.

But it was too complex. The plan did not motivate people to demand change. He realized that he needed to simplify, to be more of a preacher with a sermon than an electrical engineer with a complicated wiring diagram.

He tried other avenues. He attempted to run for parliament—but was blocked. He joined

others in forming a dissident umbrella movement, Concilio Cubano, until it was stopped by

Cuba’s secret police, the leaders taken off to jail.

Finally, Oswaldo came up with a simple, direct approach. He would collect 10,000 signatures for

a streamlined proposal that called for guarantees of freedom of speech, press, and association,

amnesty for political prisoners, the right to own private businesses, unhindered voting under a

new electoral code, and a referendum followed by new elections. He called it the Varela Project, named after Felix Varela, the 19th Century priest who was Cuba’s most illustrious educator.

The collection of signatures was extremely difficult. Payá went door to door, trying to convince people to overcome their fears, telling them the Varela Project was legal—it was in the constitution. A major breakthrough came in 1999 with the formation of a new, unified umbrella group of civil society, Todos Unidos, which helped collect the signatures. Astonishingly, over several years, at least 35,000 people signed the Varela Project, with names, addresses and identification numbers. They stood up to be counted.

The collection of signatures was extremely difficult. Payá went door to door, trying to convince people to overcome their fears, telling them the Varela Project was legal—it was in the constitution. A major breakthrough came in 1999 with the formation of a new, unified umbrella group of civil society, Todos Unidos, which helped collect the signatures. Astonishingly, over several years, at least 35,000 people signed the Varela Project, with names, addresses and identification numbers. They stood up to be counted.

But Payá discovered once again how difficult it was to confront the system. Part of the way

through collecting the signatures, Payá found that Cuba’s state security had attempted to

sabotage the effort by planting fake signatures. To rectify the problem, Payá and his teams

verified each signature three times. The first 11,020 signatures were submitted in May 2002,

and more than 14,000 the following year.

Fidel Castro just ignored them. But he did not ignore Payá, who was often in the crosshairs of

Cuba’s secret police. In 2003, 75 activists, including many who worked on the Varela Project

and Oswaldo’s closest associates, were arrested and imprisoned during the “Black Spring.” They

got long prison sentences for nothing more than collecting signatures for the Varela Project.

Payá was not arrested, but he was tormented for years by the plight of his associates. State

security went after him, too, using methods they had learned from the East German Stasi about

how to disrupt and repress dissent. Payá repeatedly received death threats. He once confided

to a friend, “I see very few chances of getting out alive.”

On July 22, 2012, he was killed after the car he was riding in was rammed from behind by a

government vehicle. The wreck has never been satisfactorily investigated.

Payá left an important legacy: he taught Cubans not to be afraid. He showed that a single,

determined voice can mobilize people for change, even in a totalitarian system. As a

commentator in Ukraine put it recently, to secure democracy you have to be ready to fight for

it relentlessly, with bare hands if necessary.

When mass demonstrations broke out on the island a year ago, many raised their hands in the

“L” for Liberación that was a sign of Payá’s movement.

David E. Hoffman is a contributing editor and member of the editorial board of The Washington Post. His new book, Give Me Liberty: The True Story of Oswaldo Paya and his Daring Quest for a Free Cuba, was just published by Simon & Schuster.

Join the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) for a conversation with The Washington Post’s David E. Hoffman, author of Give Me Liberty, and Cuban democracy activist and daughter of Oswaldo Payá, Rosa María Payá Acevedo, examining the life and work of Oswaldo Payá and how his legacy informs and inspires a new generation of Cuban democratic activists.

July 14, 2022. 12:00 pm – 01:30 pm

Lunch Available for In-Person Attendees 12:00 p.m.–12:30 p.m ET. Program and Livestream Begin at 12:30 p.m. All media must register with NED public affairs at press@ned.org.

Lunch Available for In-Person Attendees 12:00 p.m.–12:30 p.m ET. Program and Livestream Begin at 12:30 p.m. All media must register with NED public affairs at press@ned.org.

About the Speakers

David E. Hoffman is a contributing editor and member of the editorial board of The Washington Post. He was previously assistant managing editor, foreign editor, Jerusalem correspondent, Moscow bureau chief, and White House correspondent for the newspaper. Rosa María Payá Acevedo (below), the daughter of the late Oswaldo Payá, founded the citizen initiative Cuba Decide, a movement in favor of changing the political and economic systems in Cuba towards democracy, through a plebiscite. Damon Wilson is the president and chief executive officer of the National Endowment for Democracy. Kenneth Wollack is the chairman of the Board of Directors of the National Endowment for Democracy. Carl Gershman was the founding president of the National Endowment for Democracy. RSVP