Angolans head to the polls Wednesday in what is expected to be the closest election since the country first allowed a multi-party vote in 1992, TIME’s Sanya Mansoor reports. The key question is whether voters will once again pick the left-wing People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), which has run the country for half a century, or back the center-right National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA) under the charismatic Adalberto Costa Junior.

“It is a one-party regime, a big cancer that the country must get rid of,” the UNITA leader told Reuters, adding that the MPLA does not allow Angola to be a democracy.

“People don’t believe change can come from MPLA,” says Chloé Buire, a researcher at the National Center for Scientific Research in France who has spent many years studying Angola. “They are not going to accept business as usual.”

Ahead of the elections, the United States Senate has taken the unusual step of passing a resolution calling for the electoral process to be conducted fairly, peacefully and transparently, notes Maka Angola, a leading civil society group.

Ahead of the elections, the United States Senate has taken the unusual step of passing a resolution calling for the electoral process to be conducted fairly, peacefully and transparently, notes Maka Angola, a leading civil society group.

Popular frustration arising from high levels of inequality coupled with urbanization will likely push liberation movements-cum-ruling parties out of power before the end of this decade, says Marisa Lourenço, a political and economic risk expert – not just in Angola and South Africa, but in Namibia and Mozambique too.

The elections scheduled for August 24 promise to be a watershed moment in Angola’s electoral history, which has been dominated by overwhelming MPLA victories since the country emerged from civil war in 2002, says Nicolas Lippolis, a researcher at the University of Oxford’s Centre for the Study of African Economies.

A newly united opposition has emerged from an electoral alliance between UNITA, the Angolan Renaissance Party–Together for Angola (PRA-JA), and the Bloco Democrático, he writes for the Carnegie Endowment:

A newly united opposition has emerged from an electoral alliance between UNITA, the Angolan Renaissance Party–Together for Angola (PRA-JA), and the Bloco Democrático, he writes for the Carnegie Endowment:

Dubbed the United Patriotic Front and operating under the charismatic leadership of UNITA’s Adalberto Costa Júnior, this alliance is mounting a powerful electoral challenge to President João Lourenço, who was elected in 2017. With the MPLA’s popularity weakened by the social consequences of five consecutive years of recession (2015–2020) and very real perceptions of pervasive corruption, this might be the election in which the opposition massively breaks into the urban constituencies where it has been making inroads for the past decade.

On taking power Lourenco, inheriting an oil-dependent economy in recession, launched ambitious reforms to diversify revenue and privatize state-owned firms, VOA reports (above). But many are yet to see the benefits, with almost half the population living on less than $2 a day.

“The MPLA have to do a lot better, they have to tackle poverty… create jobs… deliver better services — if they don’t they’ll have a revolution on their hands,” said Cristina Roque, an independent political analyst.

“The MPLA have to do a lot better, they have to tackle poverty… create jobs… deliver better services — if they don’t they’ll have a revolution on their hands,” said Cristina Roque, an independent political analyst.

A trove of more than 700,000 documents – the Luanda Leaks (right) – obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists exposed how a global network of consultants, lawyers, bankers and accountants helped Isabel dos Santos, Africa’s richest woman and the daughter of former Angolan president José Eduardo dos Santos, amass a fortune and park it abroad.

As Election Day approaches, the United States must be prepared to use its significant influence in Angola to press the government to hold free, fair and credible elections, and should be prepared to condemn any reports of irregularities, electoral violence or arbitrary arrests of political opponents, say International Republican Institute experts Jenai Cox and Mike Brodo. In the long term, the U.S. government should increase U.S. financial and technical support for democracy and governance capacity-building programs for institutions such as the National Election Commission (CNE) and the judiciary, and for civil society organizations, independent media and political parties, they write for The Hill.

Maka Angola, a partner of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), offers several proposals for reform.

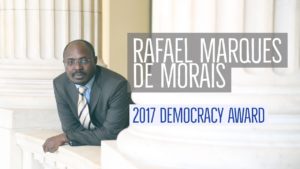

The late, former president José Eduardo dos Santos, and his daughter Isabel dos Santos in particular, had uncomfortably close ties to the diamond business, RFI reports. In 2015, a court in Angola sentenced award-winning journalist Rafael Marques, a recipient of the National Endowment for Democracy’s 2017 Democracy Award, to a six-month suspended prison term for “malicious denunciation” after he wrote a book about rights violations in the diamond industry.

The late, former president José Eduardo dos Santos, and his daughter Isabel dos Santos in particular, had uncomfortably close ties to the diamond business, RFI reports. In 2015, a court in Angola sentenced award-winning journalist Rafael Marques, a recipient of the National Endowment for Democracy’s 2017 Democracy Award, to a six-month suspended prison term for “malicious denunciation” after he wrote a book about rights violations in the diamond industry.

Regardless of the outcome of the August elections, a post-MPLA future now appears fathomable for Angola, Lippolis suggests.

The U.S. should increase support for #Angola‘s democracy & governance capacity-building programs and for civil society organizations & political parties, @IRIglobal‘s Jenai Cox & @MikeBrodo write for @thehill https://t.co/VQaJIbdOxw

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) August 22, 2022