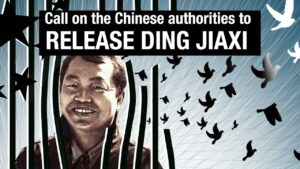

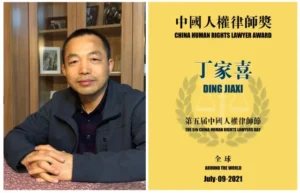

As a lead member of a band of legal activists, Ding Jiaxi, formerly a successful corporate attorney, was practicing a perilous vocation: human rights law in China. Waging a longshot battle for justice in Chinese courts, he was always under police surveillance, rarely staying long at any one place, notes Reuters reporter David Lague.

After suffering torture during more than two years in custody, Ding went on trial on charges of subverting state power. The trial lasted one day and was held behind closed doors. The verdict has yet to be announced; Ding’s fellow rights defenders expect a heavy sentence, he writes in a Special Report:

Ding is one of the highest-profile targets of the ruling Communist Party’s sprawling, multiyear clampdown on rights lawyers and legal scholars. That campaign has intensified since Xi took power a decade ago and began crushing rivals in and outside the Party. It escalated in 2015 with what’s known in China as the “709” crackdown, a reference to July 9 of that year, when security forces began arresting and harassing rights lawyers across the country. The Party’s vast internal security apparatus dwarfs this movement of idealistic legal activists – but sees it as a real threat regardless.

Ding is one of the highest-profile targets of the ruling Communist Party’s sprawling, multiyear clampdown on rights lawyers and legal scholars. That campaign has intensified since Xi took power a decade ago and began crushing rivals in and outside the Party. It escalated in 2015 with what’s known in China as the “709” crackdown, a reference to July 9 of that year, when security forces began arresting and harassing rights lawyers across the country. The Party’s vast internal security apparatus dwarfs this movement of idealistic legal activists – but sees it as a real threat regardless.

Ding suffered torture and ill treatment during his incarceration, according to the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders, a partnership of the World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT) and the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH). Activists also highlight the courageous advocacy of his wife, Shengcun “Sophie’ Luo, now based in the U.S., who has been unstinting in her efforts to get justice for her husband.

From 18th century France to the democratizing Asian tigers of South Korea and Taiwan, lawyers have been instrumental in pressuring authoritarian regimes to establish basic but potentially revolutionary legal protections, political freedoms and property rights, Lague adds.

From 18th century France to the democratizing Asian tigers of South Korea and Taiwan, lawyers have been instrumental in pressuring authoritarian regimes to establish basic but potentially revolutionary legal protections, political freedoms and property rights, Lague adds.

“In country after country, lawyers have been in the vanguard of those transitions,” said Terence Halliday, a research professor at the American Bar Foundation who has worked closely with Chinese rights defenders. “We see it time and time again, and the Chinese Communist Party has arrived at the same conclusion.”

![]() Almost 20 years ago, Columbia University political scientist Andrew J. Nathan argued in an influential Journal of Democracy essay assessing the CCP regime’s surprising durability that authoritarian states are “inherently fragile because of weak legitimacy, overreliance on coercion, over-centralization of decision making, and the predominance of personal power over institutional norms.” So, why is the Chinese Communist Party still around? The Atlantic Council’s Dexter Roberts asks.

Almost 20 years ago, Columbia University political scientist Andrew J. Nathan argued in an influential Journal of Democracy essay assessing the CCP regime’s surprising durability that authoritarian states are “inherently fragile because of weak legitimacy, overreliance on coercion, over-centralization of decision making, and the predominance of personal power over institutional norms.” So, why is the Chinese Communist Party still around? The Atlantic Council’s Dexter Roberts asks.

Counterintuitively, Harvard University’s Steven Levitsky and the University of Toronto’s Lucan Way argue in “Revolution and Dictatorship: The Violent Origins of Durable Authoritarianism” that some of China’s worst mistakes — the Great Leap Forward from 1958 to 1960, Mao’s messianic attempt to use human will to drive steel production that led to the worst famine in history, killing tens of millions; and the 1966-1976 Cultural Revolution, which set back the development of the country’s education, legal and economic systems by years — help explain the party’s longevity, Roberts writes for The Washington Post:

Counterintuitively, Harvard University’s Steven Levitsky and the University of Toronto’s Lucan Way argue in “Revolution and Dictatorship: The Violent Origins of Durable Authoritarianism” that some of China’s worst mistakes — the Great Leap Forward from 1958 to 1960, Mao’s messianic attempt to use human will to drive steel production that led to the worst famine in history, killing tens of millions; and the 1966-1976 Cultural Revolution, which set back the development of the country’s education, legal and economic systems by years — help explain the party’s longevity, Roberts writes for The Washington Post:

The authors describe how violent revolutionary regimes take actions that turn people inside and outside their countries against them; the regimes that survive emerge stronger, with an even more weakened opposition. Case in point: the Tiananmen massacre. Many Chinese now feel incapable of opposing the party and resigned to accept its worst excesses.

Today Xi continues to push the narrative of the need for a powerful Chinese state that can deliver political stability and economic prosperity through campaigns such as the “common prosperity” venture, German journalists Stefan Aust and Adrian Geiges observe in “Xi Jinping: The Most Powerful Man in the World,” Roberts adds:

Today Xi continues to push the narrative of the need for a powerful Chinese state that can deliver political stability and economic prosperity through campaigns such as the “common prosperity” venture, German journalists Stefan Aust and Adrian Geiges observe in “Xi Jinping: The Most Powerful Man in the World,” Roberts adds:

To ensure he will never be purged, nor the party toppled, Xi heavily promotes nationalism. The lessons of China’s “century of humiliation,” when European powers colonized swaths of China, are preached in the classroom to increasingly patriotic youth. …. State media trumpets China’s success in cracking down on the “black hands” behind the Hong Kong democracy movement and reports in detail on China’s missile tests threatening Taiwan. Xi wants to be seen “as the strong leader who has made China proud again and shown the world China’s true greatness.

Taipei has rebuffed China’s future plans for Taiwan as “wishful thinking” on Wednesday after Chinese Communist Party officials held a press conference to review 10 years of Xi Jinping‘s policy toward the island, Newsweek reports. The Mainland Affairs Council (MAC) rejected Beijing’s latest overtures as a “domestic political campaign to extend the CCP leader’s rule.”

“Democracy and authoritarianism are fundamentally incompatible. Beijing’s worn-out ‘one country, two systems’ rhetoric only proves the flaws of the CCP’s one-party dictatorship, which the Taiwanese people have already clearly rejected,” the MAC added.

China is relying on the pervasive use of surveillance as a key weapon in combating and defeating the lure of Western democracy, Josh Chin and Liza Lin suggest in Surveillance State: Inside China’s Quest to Launch a New Era of Social Control, Roberts continues.

China is relying on the pervasive use of surveillance as a key weapon in combating and defeating the lure of Western democracy, Josh Chin and Liza Lin suggest in Surveillance State: Inside China’s Quest to Launch a New Era of Social Control, Roberts continues.

“Under Xi, the Party thinks it has the blueprint for the rival system it has long dreamed of building,” they explain. “By mining insight from surveillance data, it believes it can predict what people want without having to give them a vote or a voice. By solving social problems before they occur and quashing dissent before it spills out onto the streets, it believes it can strangle opposition in the crib.”

As Iran, Turkey, Myanmar, and a handful of other states took steps toward becoming full members of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), research shows that the majority of SCO members are following China’s lead and trending towards “digital authoritarianism,” MIT’s Technology Review reports:

Beyond the SCO, Venezuela’s autocratic regime announced in 2017 a smart identification card for its citizens that aggregated employment, voting, and medical information with the help of the Chinese telecom company ZTE. And Huawei, another Chinese telecom corporation, boasts a global network of 700 localities with its smart city technology, according to the company’s 2021 annual report. This is up from 2015, when the company had about 150 international contracts in cities.

The China in the World (CITW) network, under Doublethink Lab (DTL), has launched its China Index, the first initiative to objectively codify the influence of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) around the world. With support from the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), the first edition of the Index provides a comparative view of PRC influence across 36 independent states and territories in nine domains: media, foreign policy, academia, domestic politics, economy, technology, society, military, and law enforcement.

The China in the World (CITW) network, under Doublethink Lab (DTL), has launched its China Index, the first initiative to objectively codify the influence of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) around the world. With support from the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), the first edition of the Index provides a comparative view of PRC influence across 36 independent states and territories in nine domains: media, foreign policy, academia, domestic politics, economy, technology, society, military, and law enforcement.

Relations between #China and the US will pose an array of geopolitical potholes as two superpowers with vastly different political and economic systems vie for domination, @AtlanticCouncil‘s @dtiffroberts @MansfieldCenter writes for @washingtonpost https://t.co/Ozz6pIeChE

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) September 22, 2022

The world has changed profoundly in the year since A World Safe for the Party, the latest survey of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) malign influence efforts. the International Republican Institute (IRI) notes.

Please join IRI – a core partner of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) – for a timely discussion on recent developments in the PRC’s global influence strategy. The event will explore findings from IRI’s forthcoming research compendium: Coercion, Capture and Censorship: Case Studies on the CCP’s Quest for Global Influence and how they reinforce or call into question shared understanding of the nature of PRC authoritarian influence, and facilitate a discussion on the democratic response.

Nick Schifrin, Foreign Affairs and Defense Correspondent for PBS News Hour, will be the event’s moderator with panelists Douglas Farah, President IBI Consultants and Johanna Kao, Regional Director of IRI Asia. IRI President Daniel Twining, PhD., will deliver welcoming remarks to guests of the event. RSVP

Following #China’s lead, research shows that the majority of #SCO member countries, as well as other authoritarian states, are quickly trending toward “digital authoritarianism,” @techreview‘s @TateRyMo reports https://t.co/p2UHBnCNrs

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) September 22, 2022