Brazilians head to the polls on Sunday to vote in a presidential runoff between current President Jair Bolsonaro and former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, commonly known as Lula, AP reports. The candidates have vastly diverging stances on issues including environmental policy, gun control, and international cooperation. The race has been marked by political violence and controversies over how social media platforms and election authorities should respond to online misinformation, the Times adds. (HT: CFR).

Democracy itself is at stake, some observers suggest.

On Monday, the IPEC polling firm had da Silva taking 50% of the vote and Bolsonaro 43%, with a margin of error of 2 percentage points, NPR adds.

Brazil started this electoral period in a way never seen in our recent history, with polarization, political violence, a proliferation of armed groups, delegitimization of the electoral process and politicization of the security forces, notes Carolina Ricardo, executive director of the Instituto Sou da Paz. But, at the same time, civil society is mobilized, and the institutions have kept at least some control of the electoral process, she writes for Open Democracy:

Brazil started this electoral period in a way never seen in our recent history, with polarization, political violence, a proliferation of armed groups, delegitimization of the electoral process and politicization of the security forces, notes Carolina Ricardo, executive director of the Instituto Sou da Paz. But, at the same time, civil society is mobilized, and the institutions have kept at least some control of the electoral process, she writes for Open Democracy:

There are many examples: demonstrations in favour of democracy, prohibition of the carrying of firearms near voting centres and prosecutors overseeing police. And the minister of the Supreme Court, Alexandre Moraes – now also president of the Superior Electoral Court, the institution responsible for conducting the electoral process – met with state commanders of the military police to ensure the security of the elections.

An absence of military intervention until now does not signal that the military ill never intervene, says Iowa State University’s Amy Erica Smith, the author of Religion and Brazilian Democracy: Mobilizing the People of God (2019). Bolsonaro’s evident openness to such intervention will be a constant threat.

An absence of military intervention until now does not signal that the military ill never intervene, says Iowa State University’s Amy Erica Smith, the author of Religion and Brazilian Democracy: Mobilizing the People of God (2019). Bolsonaro’s evident openness to such intervention will be a constant threat.

Although signs point toward a diminishing likelihood that the military will act to unseat justices or legislators, Bolsonaro’s cabinet generals will continue to rattle their sabers—and they might decide to use them someday, she writes for the Journal of Democracy. This uncertainty will be a wellspring of anxiety for the remainder of Bolsonaro’s presidency, a source of doubt that has corroded and will continue to corrode accountability.

“That Brazil is mirroring American politics should come as no surprise,” writes the Post’s Anthony Faiola. “They are both continent-sized, New World countries saddled with unresolved issues over race and the legacy of slavery. They share cultural similarities — from rodeos to evangelical voting blocs — that remain alien to most nations in Western Europe.”

Regardless of who triumphs on Sunday, uncertainty is sure to follow. With Bolsonaro’s record of undermining trust in Brazil’s electoral systems and installing military officials in government positions, experts warn that a Bolsonaro victory would be devastating, Foreign Policy reports.

Regardless of who triumphs on Sunday, uncertainty is sure to follow. With Bolsonaro’s record of undermining trust in Brazil’s electoral systems and installing military officials in government positions, experts warn that a Bolsonaro victory would be devastating, Foreign Policy reports.

If he wins, “it’ll be a disaster for democracy in Brazil,” said James Green, a professor of Brazilian history at Brown University. Bolsonaro is “trying to create what I would consider to be ‘the big lie’” in order to “create a narrative—to shore up his support,” he adds.

Many of Bolsonaro’s followers have already demonstrated their willingness to fight for him. In one of the more recent displays of political violence, a Bolsonaro-allied politician shot at and lobbed hand grenades at police who were trying to apprehend him, offering a window into how the country’s rhetoric has stoked violence and attacks.

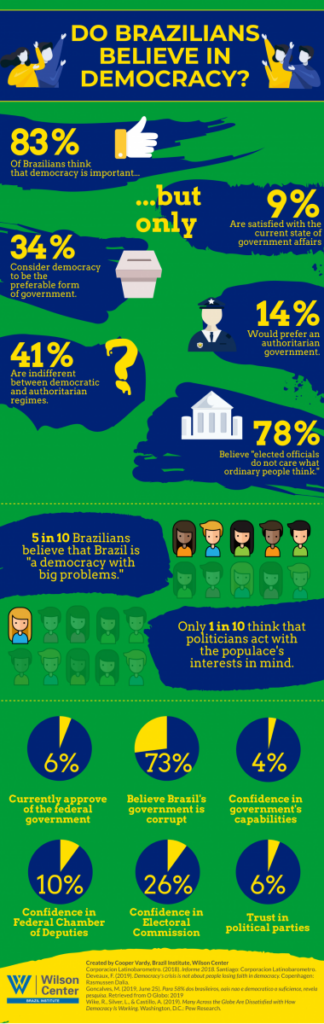

Credit: Wilson Center

Ultimately, it is a combination of both “fear and passion” that will push the public to vote on Sunday—and both camp’s supporters have sought to awaken these feelings, FP’s Catherine Osborn reports from Duque de Caxias, Brazil.

“Many Brazilians view the Oct. 30 runoff as the country’s highest-stakes election since it emerged from a military dictatorship in 1985,” she observes.

“Although Lula placed first in the initial round of voting and remains a slight favorite to win, the election of [right-wing TikTok star and congressional candidate Nikolas] Ferreira and others like him suggests that Bolsonaro and his culturally conservative, antiglobalist allies will be a force in Brazil for many years to come,” Americas Quarterly’s Brian Winter writes for Foreign Affairs.

Roots in society

“Bolsonarismo has strong roots in society,” Brazilian political scientist Camila Rocha told the Financial Times. “[Even if he loses,] he will be able to keep the movement going because he will have a lot of money and I think he will try to come back in four years.”

Five phenomena of Brazil’s past decade or two will be top of mind for many voters or structure the way in which they see their decision, adds Lauri Tähtinen, a non-resident senior associate at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) and the founder of Americas Outlook LLC. These five phenomena are (1) fallback, (2) corruption, (3) conservatism, (4) distrust, and (5) the environment.

Tähtinen outlines three possible scenarios, beginning with the baseline scenario of a narrow Lula win, the accelerating trend-based outcome of a narrow Bolsonaro win, and the decelerating trend line of a major Lula win. There is not a probability attached to any of the scenarios, but each is treated as plausible and worthy of serious consideration. A major Bolsonaro win is highly unlikely—there are no trends or starting points that indicate it—so it is not considered here in detail. In any case, it would only magnify the outcomes already present in a narrow Bolsonaro victory.

The stakes could not be higher in Brazil’s election. This election is likely to be a critical test for democracy and the rule of law in the country, with consequences that go beyond its borders, given Brazil´s size and influence, say HRW analysts Deborah Brown and Maria Laura Canineu.

The stakes could not be higher in Brazil’s election. This election is likely to be a critical test for democracy and the rule of law in the country, with consequences that go beyond its borders, given Brazil´s size and influence, say HRW analysts Deborah Brown and Maria Laura Canineu.

Yet tech platforms are predictably failing to meet the moment, even though civil society has warned about the spread election-related disinformation, they add.

What are the top priorities for the next Brazilian administration, and how will it double down on the country’s recent economic progress? the Atlantic Council asks. How can the Brazilian private sector and civil society help defuse post-election tensions and collaborate with government for economic prosperity? In what ways can the next Brazilian president bring back trust in the country’s political system? Join a public virtual discussion on the road ahead for Brazil’s next president and for US–Brazil relations. Monday, October 31, 2022, from 3:30 to 4:30 p.m. ET (16h30 to 17h30 BRT).

The stakes could not be higher, but Brazilian civil society is warning about the spread election-related disinformation, @hrw experts @deblebrown and @mlcanineu observehttps://t.co/CJ5t6pB6Ni

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) October 28, 2022