The political leaders of Mexico, Argentina, Colombia and other left-led countries in Latin America are defending Peru’s former President Pedro Castillo, ousted Dec. 7 after he announced on national television that he was dissolving the opposition-majority Congress, and that he would rule by decree, The Miami Herald reports. Hours later, the Congress ordered dismissal by an overwhelming majority of votes, and replaced him with his former vice president, Dina Boluarte.

The crisis is threatening to widen rifts in Latin America, with Boluarte’s administration saying late Wednesday that it had received the backing of governments in Chile, Ecuador, Uruguay and Costa Rica, Bloomberg adds.

Cynthia McClintock, an expert on Peru who teaches at George Washington University, told The Herald’s Andres Oppenheimer that there is no question that Castillo violated the Constitution. “It was a classic self-coup, like Fujimori’s self-coup,” she said. “There’s a feeling that Congress was out to get Castillo from the start, but none of that obscures the fact that Castillo staged a coup.”

Cynthia McClintock, an expert on Peru who teaches at George Washington University, told The Herald’s Andres Oppenheimer that there is no question that Castillo violated the Constitution. “It was a classic self-coup, like Fujimori’s self-coup,” she said. “There’s a feeling that Congress was out to get Castillo from the start, but none of that obscures the fact that Castillo staged a coup.”

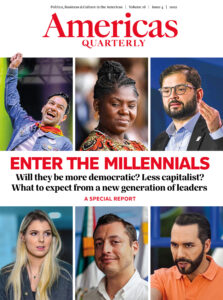

Latin America’s political landscape in 2022 was dramatic. Colombia and Brazil presented nail-biting and course-altering elections, instability deepened in Peru, and democratic backsliding continued, notes Oliver Stuenkel, the author of The BRICS and the Future of Global Order (2015) and Post-Western World: How Emerging Powers Are Remaking Global Order (2016).

The democratic recession in Central America, above all Nicaragua and El Salvador, but now also Guatemala and possibly Honduras, is likely to continue unabated, he writes for Americas Quarterly.

Like El Salvador’s Bukele, Honduran President Xiomara Castro recently suspended a number of constitutional rights in the capital Tegucigalpa to combat criminal gangs, Stuenkel adds. This slippery slope may lead to significant erosion of democratic rule and inspire copycats elsewhere. This is especially true given the very limited practical impact of regional rules as norms to protect democracy, such as the Inter-American Democratic Charter meant to help keep leaders in check.

The hemisphere’s democratic backsliding is the focus of a conversation between Inter-American Dialogue CEO Rebecca Bill Chavez and political scientist Jorge Castañeda Gutman (above). They highlight opportunities to bolster democratic norms and practices, including how (and if) the hemisphere can adopt a unified approach to build a more democratic future.

The hemisphere’s democratic backsliding is the focus of a conversation between Inter-American Dialogue CEO Rebecca Bill Chavez and political scientist Jorge Castañeda Gutman (above). They highlight opportunities to bolster democratic norms and practices, including how (and if) the hemisphere can adopt a unified approach to build a more democratic future.

Latin America is not the only region of the world where the illiberal populist temptation threatens to undermine democracy, the Bush Center’s Jessica Ludwig observes. But given the diversity of political experiences and responses evident in the region, societies around the world can learn valuable lessons about the risks of undermining the integrity of established institutions. And perhaps they can even benefit from political innovations which might emerge from Latin America that could lead to democratic renewal, rather than erosion and decay.

Rising illiberal populism and states’ reassertion of sovereignty have seriously challenged the regional human rights system, according to Reclaiming Human Rights in a Changing World Order, edited by Christopher Sabatini,* part of the Chatham House/Brookings Institution Press Insights series.

Rising illiberal populism and states’ reassertion of sovereignty have seriously challenged the regional human rights system, according to Reclaiming Human Rights in a Changing World Order, edited by Christopher Sabatini,* part of the Chatham House/Brookings Institution Press Insights series.

In the inaugural year of Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, the renowned New York Times journalist Tad Szulc started his book Twilights of the Tyrants with an optimistic sentence: “The long age of dictators in Latin America is finally in its twilight,” note Santiago Canton and Angelita Baeyens. Over the previous decade, country after country in Latin America had moved from dictatorship to democracy.

While there are important changes that should be made by the two organs of the Inter-American Human Rights System, most of the necessary reforms that would allow the system to really reach its full potential lie in the OAS and the member states themselves, they write in Polishing the Crown Jewel of the Western Hemisphere: The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights.

In the wake of the war in Ukraine, Russia is attempting to expand it’s nefarious influence in Latin America, notes David J. Kramer, Executive Director of the George W. Bush Institute. But Ukraine is trying to counter Russian efforts in the region, he adds.

In the wake of the war in Ukraine, Russia is attempting to expand it’s nefarious influence in Latin America, notes David J. Kramer, Executive Director of the George W. Bush Institute. But Ukraine is trying to counter Russian efforts in the region, he adds.

As reported by the Miami Herald, the government in Kyiv in August appointed Ambassador Ruslan Spirin as special envoy for Latin America with a particular focus on countering Russian disinformation about the war. The war, Spirin argued, is “between civilization and barbarism, a police state dictatorship and Ukraine’s democracy.”

*A former Latin America program Director at the National Endowment for Democracy (NED).