The public executions of Moshen Shekari and Majidreza Rahnavard convicted of “waging war against God” and “corruption on Earth” have triggered criticism from senior clerics in Iran, RFE/RL’s Farda Briefing reports:

Molavi Abdolhamid, an outspoken cleric, has said the death sentence against Shekari violated Islamic law. Morteza Moqtadaei, a member of the Assembly of Experts, an 88-member chamber of theologians which oversees the work of the country’s supreme leader, also criticized the judiciary for handing down the death sentence to Shekari.

Iran’s protests have become “a historic battle pitting two powerful and irreconcilable forces,” its predominantly young population, eager for change, and an aging theocracy, Carnegie Endowment expert Karim Sadjadpour observes:

Iran’s protests have become “a historic battle pitting two powerful and irreconcilable forces,” its predominantly young population, eager for change, and an aging theocracy, Carnegie Endowment expert Karim Sadjadpour observes:

Until now, the political and financial interests of Ayatollah Khamenei and the Revolutionary Guards have been intertwined. But persistent protests and chants of “Death to Khamenei” might change that. Would the Iranian security forces want to continue killing Iranians to preserve the rule of an unpopular, ailing octogenarian cleric who is reportedly hoping to bequeath power to Mojtaba Khamenei, his equally unpopular son?

Over two and a half months, women have been sending their thoughts as voice notes, writing and drawings to the BBC’s Saba Zavarei. Here are their diaries (above), with names changed for their safety. The report contains disturbing scenes.

Credit: defendlawyers

“What the people want is regime change and no return to the past,” said Nasrin Sotoudeh (right), a renowned human rights attorney and political prisoner who has previously advocated reform over revolution. “What we can see from the current protests and strikes that are now being initiated is a very real possibility of regime change.”

Even if it’s premature to propose, as have Nobel laureate Shirin Ebadi and Farideh Moradkhani (Ayatollah Khamenei’s own niece), that the world is witnessing “the beginning of the end of the Iranian regime,” there can be little doubt that a return to the status-quo is not possible, and that the protests will lead to changes, probable attempts at reform, and possible state collapse, analysts suggest.

No going back

“Present-day Iran is not the Iran of 10 or five years ago, nor of the past year or even three months,” a senior Israeli security source told Al-Monitor. “What is going on there now is deeper, broader and irreversible.”

“This is no longer a local upset or passing illness. What we are seeing is changing the face of Iran and there will be no going back.”

Iran is the only Middle Eastern state to have had two revolutions in the 20th century and its citizens today want the extinction of the Islamist regime, according to and Council on Foreign Relations expert

Iran is the only Middle Eastern state to have had two revolutions in the 20th century and its citizens today want the extinction of the Islamist regime, according to and Council on Foreign Relations expert

Iranians, unlike anyone else in the Middle East, have lived under two very different dictatorships—the Westernizing Pahlavi shahs from 1925-79 and an Islamic theocracy since 1979—and they’ve rejected both, they write for The Wall Street Journal:

Belief in the value of a constitution and representative government is more than an imported, debased Western idea to Iranians. Iran embraced a written code of laws as a means of checking foreign influence in the Constitutional Revolution of 1905-11. Iranians have a 120-year history of using street demonstrations to check abusive power. Unlike past protests in other Middle Eastern countries, today’s popular rebellion in Iran could usher in a lasting pluralistic order.

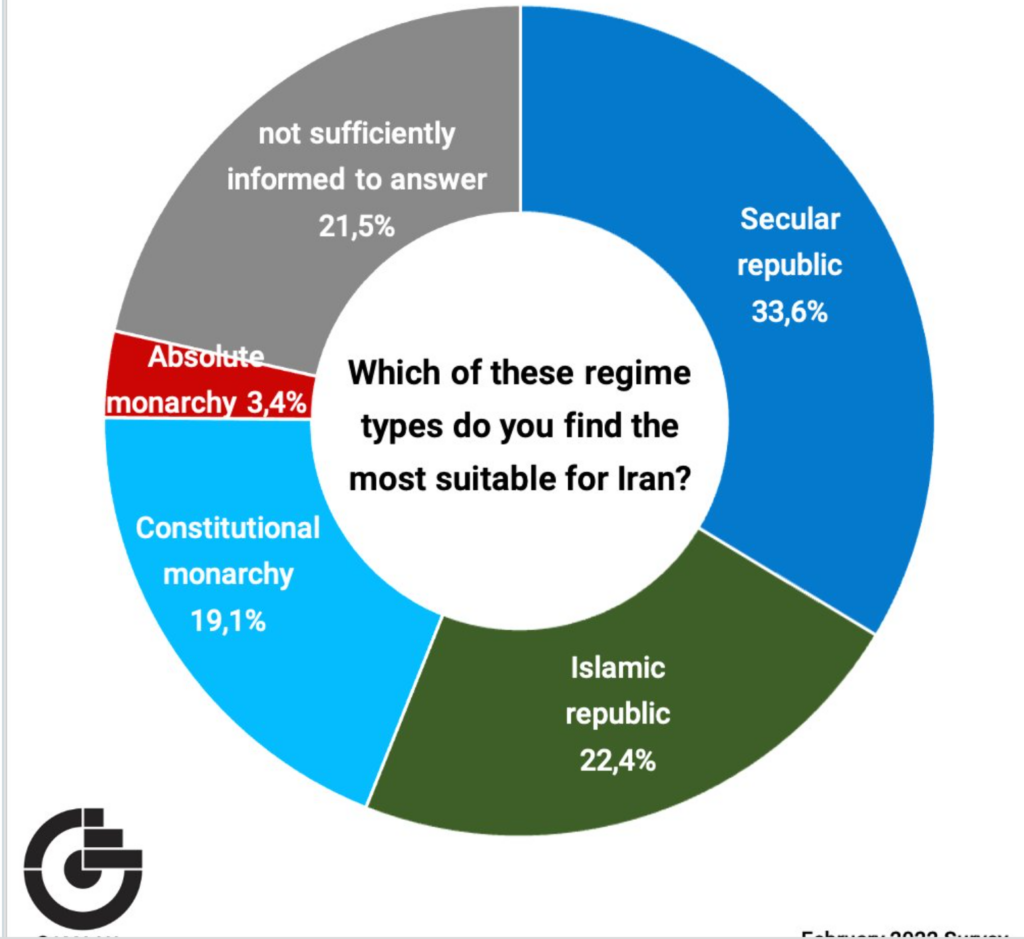

Only 22% of Iranians support the idea of an Islamic Republic, according to a survey by the Group for Analyzing and Measuring Attitudes in Iran (GAMAAN). The findings show increased secularization of the population with 47% of respondents stating that they had changed from being religious to non-religious, said GAMAAN, which worked with Ladan Boroumand, a Lech Walesa Prize recipient for her work to promote democratization in Iran.

The Iranian regime has replaced key clerics responsible for indoctrinating a significant portion of the security forces, possibly to improve efforts to ideologically control security officers, according to the Critical Threats Project’s Iran Crisis Updates. Senior cleric Abdollah Hajji Sadeghi appointed three new clerics to key leadership posts in the Basij Organization on December 13.[1] Hajji Sadeghi is responsible for representing Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei to the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC).

Iranian conservatives were unprepared when the protests erupted. Tensions between young women and the authorities over forced hijab wearing have been bubbling for years, but conservatives paid little attention, notes Djavad Salehi-Isfahani, professor of economics at Virginia Tech and an associate of the Middle East Initiative at Harvard Kennedy School.

Iranian conservatives were unprepared when the protests erupted. Tensions between young women and the authorities over forced hijab wearing have been bubbling for years, but conservatives paid little attention, notes Djavad Salehi-Isfahani, professor of economics at Virginia Tech and an associate of the Middle East Initiative at Harvard Kennedy School.

The pro-poor policies of the early Islamic revolutionaries provided electricity, clean water and health services to rural and poor urban areas, transforming many women’s lives, he writes for Qantara. Today, however, women in Iran marry in their mid-to-late twenties and have two children on average. Thirty-eight percent of Iranian women in their twenties have at least some higher education, compared to 33% of men in their age cohort. To them, the mere thought that they could be arrested and dragged to a re-education camp by the morality police is intolerable.

Four decades of the Islamic Republic’s hard power will ultimately be defeated by two millenniums of Iranian cultural soft power, Carnegie’s Sadjadpour writes for The Times. The question is no longer about whether this will happen but when. History has taught us that there is an inverse relationship between the courage of an opposition and the resolve of a regime, and authoritarian collapse often goes from inconceivable to inevitable in days.

The truth — obvious to all of Iranian society — is that the despotic clerics are the ones who are afraid. If they do not change, the people might force change. https://t.co/gam70kebgr

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) December 14, 2022