And yet, Ukraine was fighting back. Ukrainian history makes today’s world make more sense, he writes for The Washington Post:

And yet, Ukraine was fighting back. Ukrainian history makes today’s world make more sense, he writes for The Washington Post:

Our entire Western civilization trajectory, from the Greeks forward, is clearer if we understand that Athens was fed by what is now southern Ukraine. The fantastic history of the Vikings becomes still more so when we understand that they founded a state in Kyiv. The age of exploration takes on a new dimension when we recognize that Polish and Russian powers made their empires by pushing east into the Eurasian landmass, where they ultimately met in Ukraine. The age of empire is completed by Nazi and Soviet neo-imperial projects, both of which had their focus in Ukraine.

That horribly bloody confrontation made Ukraine the most dangerous place in the world during the totalitarian era of 1933 to 1945, adds Snyder, the author of “The Road to Unfreedom” and “Bloodlands.” His updated audio edition of “On Tyranny” includes 20 new lessons about Ukraine.

On February 24, 2022, when Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, it was not just another news story for the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) —it was personal, as the brutal war put colleagues, grantees, family, and friends at terrible risk, the NED reports (above). Despite the danger, courageous Ukrainian partners continued their work during the war to document war crimes and atrocities; advocate for international support, mobilize thousands of volunteers across the country; provide independent news, and promote government transparency and accountability.

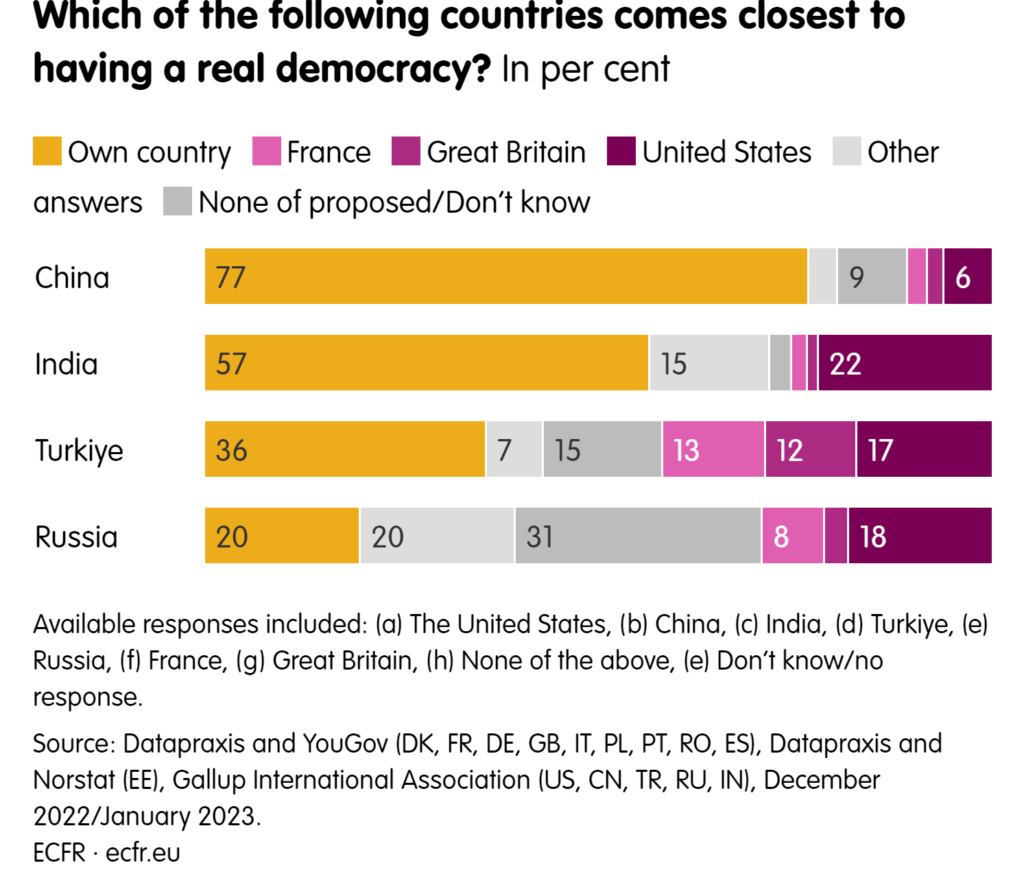

While Western figures may depict the conflict as one of autocracy vs. democracy to unify the West, it offers no sure-fire way to appeal to citizens in non-Western countries, analysts Timothy Garton Ash, Ivan Krastev and Mark Leonard write for the European Council on Foreign Relations. On the contrary: in the view of many people outside the West, their own countries are also democracies – and are perhaps even the best democracies, according to an ECFR survey:

While Western figures may depict the conflict as one of autocracy vs. democracy to unify the West, it offers no sure-fire way to appeal to citizens in non-Western countries, analysts Timothy Garton Ash, Ivan Krastev and Mark Leonard write for the European Council on Foreign Relations. On the contrary: in the view of many people outside the West, their own countries are also democracies – and are perhaps even the best democracies, according to an ECFR survey:

Other results in our poll further suggest that people in China, India, and Turkiye are sceptical of claims about defending democracy. Many in China state that American and European support for Ukraine is driven by the desire to protect Western dominance. And for the vast majority of Chinese and Turks, Western support for Ukraine is motivated by reasons other than a defence of Ukraine’s territorial integrity or of its democracy.

Zbigniew Brzezinski famously wrote, “without Ukraine, Russia ceases to be a Eurasian empire,” notes analyst Anatol Lieven. So the hope expressed in various Western circles that as a result of complete defeat in Ukraine, not only would the Putin regime be toppled, but the Russian Federation itself would be radically and permanently weakened or even disintegrate is not an altogether empty vision, he writes for TIME. As the examples of Iraq and Libya demonstrate, in multi-ethnic authoritarian states with weak civil institutions, regime and state can be so deeply intertwined that the destruction of one leads to the collapse of the other.

If the war continues as a bloody stalemate after a summer of fighting the momentum for peace – including territorial losses of Ukraine – over justice in the sense of a complete defeat for Putin will grow, says Owen Matthews, the author of Overreach: The Inside Story of Putin’s War Against Ukraine.

If the war continues as a bloody stalemate after a summer of fighting the momentum for peace – including territorial losses of Ukraine – over justice in the sense of a complete defeat for Putin will grow, says Owen Matthews, the author of Overreach: The Inside Story of Putin’s War Against Ukraine.

As former US Under-Secretary of State Rose Gottemoeller told me recently “there can be no return to the status quo ante” after the war – while in the same sentence insisting that “international law must be respected.” Tragically for Ukraine, both those things cannot simultaneously be true, he writes for the IAI.

The declaration that “there’s no free Poland without a free Ukraine”—often attributed to Poland’s founding father, Jozef Pilsudski—that bound Poles and Ukrainians to stop Soviet imperialism in 1919 rings equally true today, note Pawel Markiewicz, executive director of the Washington office of the Polish Institute of International Affairs, and Maciej Olchawa, the Kosciuszko Foundation scholar at Loyola University Chicago. At the time, the Red Army was planning on igniting world revolution but was stopped and turned back by Polish and Ukrainian forces.

Credit: NDI

Then, as today, the slogan proves that the notion of a Europe without a sovereign Ukraine is no longer conceivable, they write for Foreign Policy. For Kyiv and Warsaw, the prosperity of one is pinned to the success and stability of the other. The opening lines of the two countries’ national anthems are nearly identical: “Poland/Ukraine is not yet lost,” conveying a unique characteristic of national obstinacy to survive partition, occupation, or enemy aggression. Both were penned in defiance of Russian imperialism.

A year after Russia’s invasion, Ukraine has emerged as a leader in contesting the Kremlin’s industrial scale dissembling, according to a new report released by the NED’s International Forum for Democratic Studies.

Relying on dozens of interviews and a series of convenings with experts from across Europe, Shielding Democracy: Civil Society Adaptions to Kremlin Disinformation about Ukraine examines how crucial adaptations by civil society organizations are helping Ukraine push back on the Kremlin’s multi-pronged effort to justify its unprovoked invasion.

Key advantages—including deep preparation, open networks of cooperation, and active use of new technology—that have allowed Ukraine to tell its story and build resilience, say co-authors Galyna Petrenko of Detector Media; Veronika Víchová of European Values Center for Security Policy; and Adam Fivenson of the International Forum.

Key advantages—including deep preparation, open networks of cooperation, and active use of new technology—that have allowed Ukraine to tell its story and build resilience, say co-authors Galyna Petrenko of Detector Media; Veronika Víchová of European Values Center for Security Policy; and Adam Fivenson of the International Forum.

“Ukraine has distinguished itself as a powerful counterforce to Kremlin aggression, including important innovation in the information sphere. The nongovernmental sector has served as a catalyst for Ukraine’s success,” said Christopher Walker, NED’s Vice President for Studies and Analysis. “The world has much to learn from our Ukrainian partners, who are at the leading edge of the response to the ever-adapting threat posed by the Kremlin’s corrosive ambitions in the information domain.”

The NED hosted a virtual discussion with Peter Pomerantsev (Johns Hopkins University), Olha Bilousenko (Detector Media, Ukraine), and report authors Veronika Víchová and Adam Fivenson to share lessons from civil society’s innovative efforts to neutralize and repel Moscow’s malign narratives.

The NED hosted a virtual discussion with Peter Pomerantsev (Johns Hopkins University), Olha Bilousenko (Detector Media, Ukraine), and report authors Veronika Víchová and Adam Fivenson to share lessons from civil society’s innovative efforts to neutralize and repel Moscow’s malign narratives.

The event is also available on NED’s website.