Georgia’s Prime Minister Irakli Garibashvili today congratulated war veterans on the May 9 Victory Day over Nazi Germany and then answered journalists’ questions, not missing the chance to once again slam the “unsuccessful” and “bankrupt” opposition and speak of traditional values.

Rights groups and Western experts have criticized the Georgian Dream government, which enjoys a parliamentary supermajority, for backsliding on its democratization commitments, thus dimming prospects for the country’s long-held goal of European Union accession, reports suggest.

In her state-of-the-nation speech in late March, Georgian President Salome Zourabichvili accused the governing party of adopting authoritarian and illiberal tactics. “Georgian Dream has been slowly drained of dissenting opinion and alternative political views,” Zourabichvili said.

Georgia has implemented 80% of the European Commission’s recommendations to earn EU candidate status, as Tbilisi races to convince it to progress to the next steps in the bloc’s accession process, the country’s Foreign Minister Ilia Darchiashvili told EURACTIV:

Georgia has implemented 80% of the European Commission’s recommendations to earn EU candidate status, as Tbilisi races to convince it to progress to the next steps in the bloc’s accession process, the country’s Foreign Minister Ilia Darchiashvili told EURACTIV:

The EU stopped short of granting Georgia candidate status in June 2022 while awarding it to Ukraine and Moldova, calling on Tbilisi to reform the justice and electoral systems, improve press freedom and limit the power of oligarchs. Despite the progress, the government has not yet fully implemented reforms addressing the most significant problems highlighted by the European Commission, analysts and civil society organisations say.

“The discussion of this draft [ “foreign agents” law on NGOs] has also skyrocketed polarisation between the ruling party and the opposition, the ruling party and the media and the ruling party and the civil society,” Paata Gaprindashvili, director of the think tank Georgia’s Reforms Associates (GRASS) and former Georgian ambassador, told EURACTIV.

National Endowment or Democracy (NED)

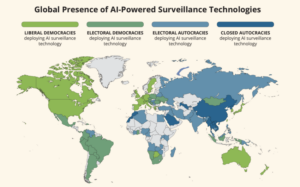

A report based on research conducted by the Tbilisi-based Institute for the Development of Freedom of Information (IDFI), noted that while Artificial Intelligence applications can enhance the reform process, “these same applications can endanger democratic principles–especially if state accountability is already tenuous due to shortcomings in judicial independence, government transparency, or law-enforcement oversight mechanisms.”

“Guarding against the abuse or misuse of AI tools is particularly critical in the public security context, especially since Georgia’s law enforcement agencies are criticized frequently for their opaque practices,” said the report, published with support from the National Endowment for Democracy (NED)’s International Forum for Democratic Studies.

The Georgian people remain strongly oriented towards Europe and the West, says Francis Fukuyama, director of the International Policy program at Stanford University’s Freeman Spogli Institute. A recent poll by the International Republican Institute showed 63 percent of respondents asserting that the EU was the country’s most important political partner, with 47 percent saying the same about the United States. Only 8 percent felt that way about Russia, while 87 percent felt Russia constituted the greatest political threat.

The Georgian people remain strongly oriented towards Europe and the West, says Francis Fukuyama, director of the International Policy program at Stanford University’s Freeman Spogli Institute. A recent poll by the International Republican Institute showed 63 percent of respondents asserting that the EU was the country’s most important political partner, with 47 percent saying the same about the United States. Only 8 percent felt that way about Russia, while 87 percent felt Russia constituted the greatest political threat.

The most disturbing acts of the Georgian Dream government are internal ones, however. It has jailed the country’s third president, Mikheil Saakashvili, arrested a leader of the country’s remaining independent news outlets, and introduced the “foreign agents” law, he writes for American Purpose:

As Nino Evgenidze (above) and I argued recently in Foreign Affairs, these acts seem deliberately designed to torpedo Georgia’s chances of getting into the European Union. The Western response should not be to deny Georgia entry, but to set clear conditions for proceeding that would roll back the anti-democratic measures recently taken.

At the anti-NGO protests, homemade signs in Georgian and English pledging allegiance to Europe and denouncing Russia mingled with Georgian and EU flags, Andrew Cockburn writes for the London Review of Books:

At the anti-NGO protests, homemade signs in Georgian and English pledging allegiance to Europe and denouncing Russia mingled with Georgian and EU flags, Andrew Cockburn writes for the London Review of Books:

None of the signs was in Russian, and I didn’t see or hear any of the sixty thousand or more Russians who have decamped to Georgia since the start of the war, an unpopular influx that, while boosting the economy (which grew 10 per cent last year), has greatly increased the cost of living – rents have doubled in Tbilisi. Graffiti reading ‘Deport Russians’ has started to appear on city walls. To the outside world, the anti-Russian mood seems to confirm that Georgia is divided, as Ukraine was in 2013, between a popular pro-Western opposition and a regime taking its orders from the Kremlin.

A number of authoritative Georgian civil society organizations addressed the Open Government Partnership Steering Committee with a letter underlying the necessity to safeguard Georgian democracy, civic space, and free media, Civil Georgia notes.

A number of authoritative Georgian civil society organizations addressed the Open Government Partnership Steering Committee with a letter underlying the necessity to safeguard Georgian democracy, civic space, and free media, Civil Georgia notes.

The opposition is currently highly fragmented, and the 5 percent threshold means that many of the small liberal parties will waste their voters’ ballots and not get into parliament, former NED board member Fukuyama adds. The oldest opposition party, Saakashvili’s United National Movement, remains even less popular than Georgian Dream. It is critical for the other pro-European groups to unite around common candidates and a platform that clearly renounces Georgia’s reincorporation into the Russian sphere of influence.