A previously unreported meeting is an example of how the Chinese government directly — and often secretly — engages in political activity in Australia, making the nation a laboratory for testing how far it can go to steer debate and influence policy inside a democratic trade partner, The New York Times reports:

A previously unreported meeting is an example of how the Chinese government directly — and often secretly — engages in political activity in Australia, making the nation a laboratory for testing how far it can go to steer debate and influence policy inside a democratic trade partner, The New York Times reports:

Chinese consul general Gu Xiaojie called on the group to help shape public opinion during a coming visit of China’s prime minister, Li Keqiang, in part by reporting critics to the consulate. Rallies in support of China should be coordinated, he suggested, and large banners should be unfurled to block images of protests against Beijing…..China once sought to spread Marxist revolution around the world, but its goal now is more subtle — winning support for a trade and foreign policy agenda intended to boost its geopolitical standing and maintain its monopoly on power at home.

“We are not troops, but this task is a bit like the nature of troops,” said the diplomat, Chinese consul general Gu Xiaojie, according to a recording of the session in the consulate obtained by The New York Times and verified by a person who was in the room. “This is a war,” he added, “with lots of battles.”

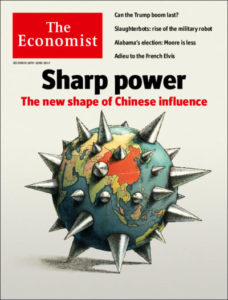

Even if dictatorships tend to be more brittle than democracies, President Xi Jinping has reasserted party control and begun to project Chinese power around the world, The Economist observes:

Even if dictatorships tend to be more brittle than democracies, President Xi Jinping has reasserted party control and begun to project Chinese power around the world, The Economist observes:

America complains that China is cheating its way to the top by stealing technology, and that by muscling into the South China Sea and bullying democracies like Canada and Sweden it is becoming a threat to global peace. China is caught between the dream of regaining its rightful place in Asia and the fear that tired, jealous America will block its rise because it cannot accept its own decline.

Australia has a valuable base of experience in facing up to the challenge of PRC sharp power projection, said Christopher Walker, the National Endowment for Democracy’s Vice President for Studies & Analysis. Several key steps, drawn from the NED’s Sharp Power report, can be taken to address Beijing’s influence efforts, he told the U.S. House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence hearing on “China’s Foreign Influence and Sharp Power Strategy to Shape and Influence Democratic Institutions”:

- Address the evident knowledge and capacity gap on China. Throughout many societies in which China today is deeply engaged information concerning the Chinese political system and its foreign policy strategies tends to be extremely limited. This places many societies at a distinct strategic disadvantage. There often are few journalists, editors, and policy professionals who possess a deep understanding of China—the Chinese Communist Party, especially—and can share their knowledge with the rest of their societies in a systematic way. Given China’s growing economic, media, and political footprint in these settings, there is a pressing need to build capacity to disseminate independent information about China and its regime. Civil society organizations should develop strategies for communicating expert knowledge about China to broader audiences.

Shine a spotlight on authoritarian influence. Chinese sharp power relies in part on disguising state-directed projects as commercial media or grassroots associations, for example, or using local actors as conduits for foreign propaganda or tools of foreign manipulation. To respond to these efforts at misdirection, observers need the capacity to put them under the spotlight and analyze them in an independent and comprehensive manner.

Shine a spotlight on authoritarian influence. Chinese sharp power relies in part on disguising state-directed projects as commercial media or grassroots associations, for example, or using local actors as conduits for foreign propaganda or tools of foreign manipulation. To respond to these efforts at misdirection, observers need the capacity to put them under the spotlight and analyze them in an independent and comprehensive manner.- Safeguard democratic societies against undesirable Chinese Party State influence. Once the nature and techniques of authoritarian influence efforts are exposed, countries should build up internal defenses. Authoritarian initiatives are directed at cultivating relationships with the political elites, thought leaders, and other information gatekeepers of open societies. Such efforts are part of Beijing’s larger aim to get inside such systems in order to incentivize cooperation and neutralize criticism of the authoritarian regime. Support for strong, independent civil society—including independent media—is essential to ensuring that the citizens of democracies are adequately informed to evaluate critically the benefits and risks of closer engagement with Beijing and its surrogates. …..

- Reaffirm support for democratic values and ideals. If one goal of authoritarian sharp power is to legitimize nondemocratic forms of government, then it is only effective to the extent that democracies and their citizens lose sight of their own principles. The Chinese government’s sharp power seeks to undermine democratic standards and ideals. Top leaders in the democracies must speak out clearly and consistently on behalf of democratic ideals and put down clear markers regarding acceptable standards of democratic behavior. Otherwise, the authoritarians will fill the void.

- Learn from democratic partners. A number of countries, Australia especially, have already had extensive engagement with China and can serve as an important point of reference for countries whose institutions are at an earlier stage of their interaction with Beijing.36 Given the complex and multifaceted character of Beijing’s influence activities, such learning between and among democracies is critical for accelerating responses that are at once effective and consistent with democratic standards. RTWT