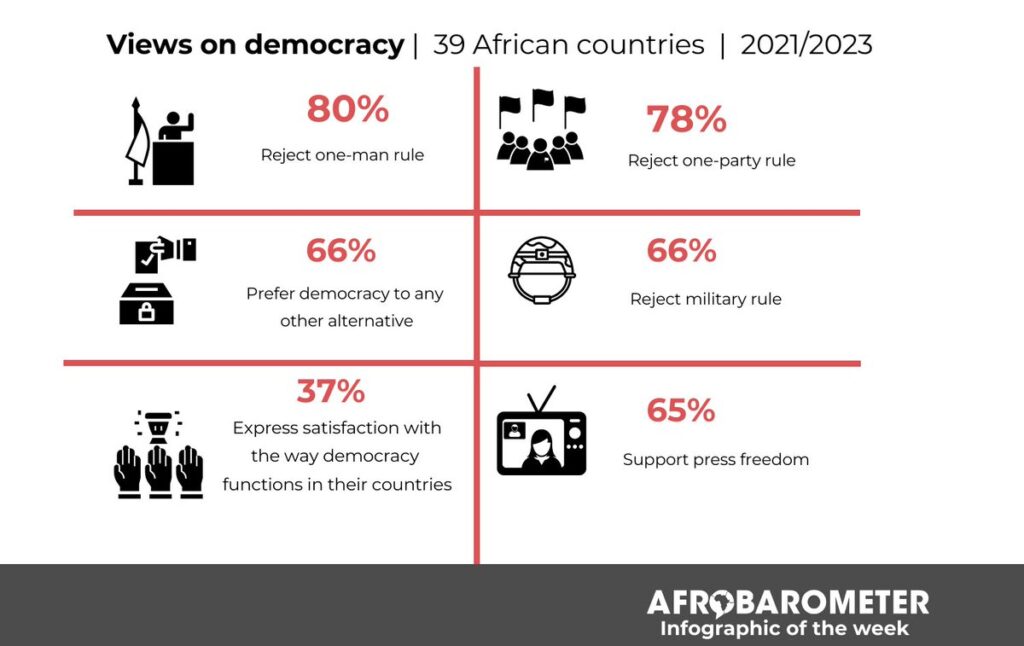

Many Africans have lost faith in democracy, The Economist notes. Afrobarometer, a pollster, found that the share who prefer democracy to any other form of government has fallen from 75% in 2012 to 66%. That may sound like a solid majority, but it includes many waverers. An alarming 53% said a coup would be legitimate if civilian leaders abuse their power, which they often do. In South Africa, which has one of the world’s most liberal constitutions, 72% say that if a non-elected leader could cut crime and boost housing and jobs, they would be willing to forgo elections.

Many Africans have lost faith in democracy, The Economist notes. Afrobarometer, a pollster, found that the share who prefer democracy to any other form of government has fallen from 75% in 2012 to 66%. That may sound like a solid majority, but it includes many waverers. An alarming 53% said a coup would be legitimate if civilian leaders abuse their power, which they often do. In South Africa, which has one of the world’s most liberal constitutions, 72% say that if a non-elected leader could cut crime and boost housing and jobs, they would be willing to forgo elections.

While recent coups are cause for concern, autocratic governance is neither inevitable—nor irreversible, according to a leading analyst.

In multiple surveys spanning two decades, ordinary citizens across Africa have consistently expressed their desire to live under governments that are both democratic and accountable, notes E. Gyimah-Boadi, co-founder and board chair of Afrobarometer.

In multiple surveys spanning two decades, ordinary citizens across Africa have consistently expressed their desire to live under governments that are both democratic and accountable, notes E. Gyimah-Boadi, co-founder and board chair of Afrobarometer.

In the latest surveys (2021-2022), an average of two-thirds of the respondents (66%) expressed a preference for democracy over any other system of government, he writes for The Wilson Quarterly. They also rejected non-democratic alternatives like one-man rule (80%), one-party rule (78%), and military rule (67%). Even more reassuringly, support for media freedom increased by 12% between 2014 and 2022; preference for accountable governance over effective governance went up by 7%, and the need for the president to comply with court decisions rose by 5%.

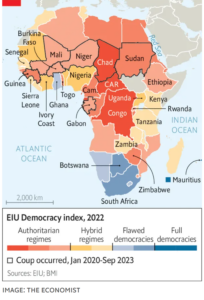

So long as Africans see—and experience—“democracy” as a charade played by corrupt elites with the help of foreigners, then many will consider other options. What those look like will vary depending on the context, The Economist suggests:

So long as Africans see—and experience—“democracy” as a charade played by corrupt elites with the help of foreigners, then many will consider other options. What those look like will vary depending on the context, The Economist suggests:

Africans are frustrated with the sham that passes for “democracy” in most countries. They are also fed up with flimsy states that provide neither security nor prosperity. Around two-thirds of them, as well as majorities in 28 of 36 polled countries, feel their countries are heading in the wrong direction. Should this continue, many Africans, especially younger ones, may be tempted to reconsider shabby social contracts—and look for radical change.

The recent coup in Gabon was “a change in hats”, nothing more, said Dave Peterson, senior director of the Africa Program at the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). “Clearly, if you want to go back in terms of events, the collapse of the Gaddafi regime in Libya began to exacerbate the insecurity in Mali and across the Sahel,” he told Al Jazeera.

We currently stand at a precipice. Africans prefer democratic governance, but democratic dividends are backsliding due to misgovernance. We must restore faith in the dividends of democracy. While democracy is desirable on its own merit, it’s not edible. Considering Africa’s problems, democracy must deliver tangible goods, adds Gyimah-Boadi, the co-founder and former executive director of Ghana Center for Democratic Development:

First, we must support African pro-democracy and accountable governance reformers. Governments hardly change on their own unless pushed. Often, strides have been made in good governance not because of the government, but in spite of it. For decades, African civil society organizations have been pushing hard to force the transition to democratic governance, to ensure the integrity of elections, to help enact laws for best practices in good governance, and to hold governments accountable. A good example of this is Ghana’s civil society-driven Right to Information Act (Act 989). Enacted in 2019, it has given Manasseh Azure Awuni and The Fourth Estate investigative journalist group for which he is editor-in-chief, the constitutional right to access information held by public institutions.

First, we must support African pro-democracy and accountable governance reformers. Governments hardly change on their own unless pushed. Often, strides have been made in good governance not because of the government, but in spite of it. For decades, African civil society organizations have been pushing hard to force the transition to democratic governance, to ensure the integrity of elections, to help enact laws for best practices in good governance, and to hold governments accountable. A good example of this is Ghana’s civil society-driven Right to Information Act (Act 989). Enacted in 2019, it has given Manasseh Azure Awuni and The Fourth Estate investigative journalist group for which he is editor-in-chief, the constitutional right to access information held by public institutions. Second, let’s go back to what works. We should take lessons from the past, when Western nations and international finance institutions worked together with African governments and civil society, continental and sub-regional bodies, and international partners to secure debt relief, reduce poverty, and end civil wars. This was sometimes achieved through reform-conditioned development aid and other expressions of “soft power.” The design of the US’ Millennium Challenge Compact stands out for its power to motivate democratic governance. RTWT

Second, let’s go back to what works. We should take lessons from the past, when Western nations and international finance institutions worked together with African governments and civil society, continental and sub-regional bodies, and international partners to secure debt relief, reduce poverty, and end civil wars. This was sometimes achieved through reform-conditioned development aid and other expressions of “soft power.” The design of the US’ Millennium Challenge Compact stands out for its power to motivate democratic governance. RTWT

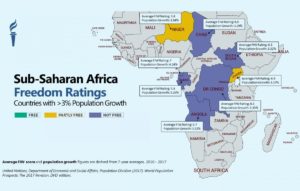

The main reason to wish for progress in Africa is to benefit Africans. But the rest of the world has a stake, too, The Economist adds:

Africa is the only continent where population growth is fast. By 2030 nearly one in three people entering working age will live there. Many of humanity’s big challenges, from climate change to pandemics, will be harder to tackle if Africa is dysfunctional. There is no guarantee a more democratic Africa will be prosperous and peaceful, but one ruled by autocrats and generals will surely not be.

*A partner of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED).