POMED

Thousands of Tunisians protesting against President Kais Saied’s seizure of political power four months ago tried to march on the suspended parliament on Sunday, as hundreds of police blocked off the area, Reuters reports.

The march coincided with the formation of a new coalition – Citizens Against the Coup – which has endorsed the Democratic Initiative, a roadmap for the restoration of democracy.

Nahda [aka Ennahda], a part of most governments since the revolution, has become a target of public anger. Many Tunisians blame it for the deteriorating economy and the gridlock that defined parliament before Saied’s coup. It is still the biggest and most organized party in the country, but its unpopularity makes it difficult to lead any action against the president, the Financial Times reports:

Nahda [aka Ennahda], a part of most governments since the revolution, has become a target of public anger. Many Tunisians blame it for the deteriorating economy and the gridlock that defined parliament before Saied’s coup. It is still the biggest and most organized party in the country, but its unpopularity makes it difficult to lead any action against the president, the Financial Times reports:

“Under the best scenario, Saied will become convinced to open up to political elites and the UGTT [labor union] when economic and social problems emerge because things could get too chaotic,” said Tarek Kahlaoui, a political analyst. “This could lead to a new political system that is perhaps more presidential but with checks and balances.” But he and others also mention the potential for a more negative evolution if anger at economic conditions erupts on the streets. Youssef Cherif, who heads Columbia Global Centers in Tunis, said Saied would either have “to repress or negotiate”. In a worst-case scenario, he added, the erosion of Saied’s popularity could precipitate a coup against him from the military or police.

“His biggest mistake is that he opened a Pandora’s box without calculating all the risks,” Cherif said. “What is dangerous is that his failure could mean the worst system would emerge.”

Life after Tunisia’s coup: ‘This is a moment of counter revolution’ https://t.co/MegTphlK4u

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) November 16, 2021

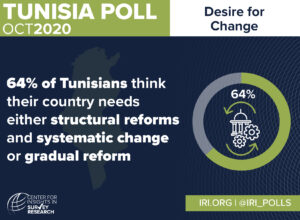

Contrary to some Western and Middle East media, most Tunisians do not see themselves or their president as burying a “democracy” whose promised economic and social benefits they never enjoyed, argues Francis Ghilès, Senior Associate Researcher at Barcelona’s Centre for International Affairs. Many Tunisians see themselves and their president as fighting a state captured by corrupt political and business lobbies which were leading it to ruin, he asserts.

ICDR Statement on the recent anti-democratic actions in Tunisia

President Kais Saied’s moves have exposed critical weaknesses within the region’s only nascent democracy but it is too early to assert whether Tunisia’s democratization is truly ephemeral, say analysts Chuchu Zhang and Yahia H Zoubir. However, the ongoing political instability and bickering between secular and Islamist elites has exposed three key vulnerabilities of the transition process– ideological polarization, overemphasis on consensus, and an immature party system – they write for the Georgetown Journal of International Affairs:

- First, the early days of Tunisia’s post-revolutionary political milieu were characterized by intense ideological polarization between Islamists and secularists….. This pattern has caused the critical challenges Tunisia faces to be interpreted as ideological sparring rather than pressing socioeconomic challenges. Consequently, democratic institutions have failed to generate an effective government capable of addressing the root causes of the 2010-2011 revolution….

- Second, Tunisian consensus politics have begun to falter. When ideological fractures reached their peak in mid to late 2013, various parties and organizations tried to find common ground, make substantial concessions, and balance the interests of major stakeholders. These decisions mitigated political tensions, enabled Tunisia to avoid civil war, and resulted in the country’s political actors receiving the 2015 Nobel Peace Prize. …. Alas, this national unity framework did not resolve the underlying ideological cleavages between leading parties. Insistence on consensus has instead thwarted the emergence of a genuine and effective political opposition. …. . This consensus-based approach also led the parties to deliberately avoid difficult and controversial issues. …. The result was a widening gap between political elites and citizens, who believe that their interests have not been appropriately represented.

- Third, deficiencies in Tunisia’s party system contributed to the broader weakness of the country’s democracy. Tunisia, lacking a tradition of genuine political pluralism, witnessed a proliferation of dozens of insignificant political parties following the 2010-2011 revolution. Most of them are personality-driven and lack clear programs, positions, or coherent political visions…. Due to a lack of internal democracy, these parties have followed the “iron law of oligarchy,” whereby the parties’ decision-makers develop oligarchic tendencies, prioritize personal ambitions and gains over institutional improvements, and marginalize rank and file members.

The indecisive attitude of international democratic actors has disappointed many and created a power vacuum for MENA strongmen to extend their political influence on Tunisia, some suggest.

The indecisive attitude of international democratic actors has disappointed many and created a power vacuum for MENA strongmen to extend their political influence on Tunisia, some suggest.

But it is a mistake to suggest that Tunisia will choose either assistance from the West or from the Gulf, and that that choice will set Tunisia on a path to either restoring democracy or consolidating autocracy, adds Sharan Grewal, a Nonresident Fellow at Brookings’ Center for Middle East Policy. By this logic, the policy implication might be for the West not to press for democracy too strongly, for fear that it will push Saied to choose the Gulf, he observes:

The West and the Gulf are not necessarily alternative sources of funding. Egypt’s Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi received $12 billion in Gulf funding in the wake of his 2013 coup, yet still courted and received an IMF loan by 2016. In Tunisia as well, it is unlikely that the Gulf can solve the country’s economic woes forever – even if they happen to patch up the budget deficit this year, Tunisia will eventually go back to the IMF. With the Gulf bogged down in supporting counter-revolutionary forces in Egypt, Libya, and Sudan, that return may come sooner rather than later. Knowing that, the West should double down on its pressure for democracy and dialogue, not abandon it.

POMED

Moreover, the West would be better off leaning on the Gulf to drop their more nefarious conditions of dissolving political parties, Grewall notes. That will neither revitalize democracy nor lead to stability in Tunisia.

Military courts are increasingly targeting civilians, in some cases for publicly criticizing President Kais Saied, said Amnesty International. “Civilians should never be tried in military courts. Yet in Tunisia, the number of civilians brought before the military justice system appears to be increasing at an alarming rate – in the past three months alone, more civilians have faced military courts than did in the preceding ten years,” said Heba Morayef, Amnesty International’s Regional Director for the Middle East and North Africa.

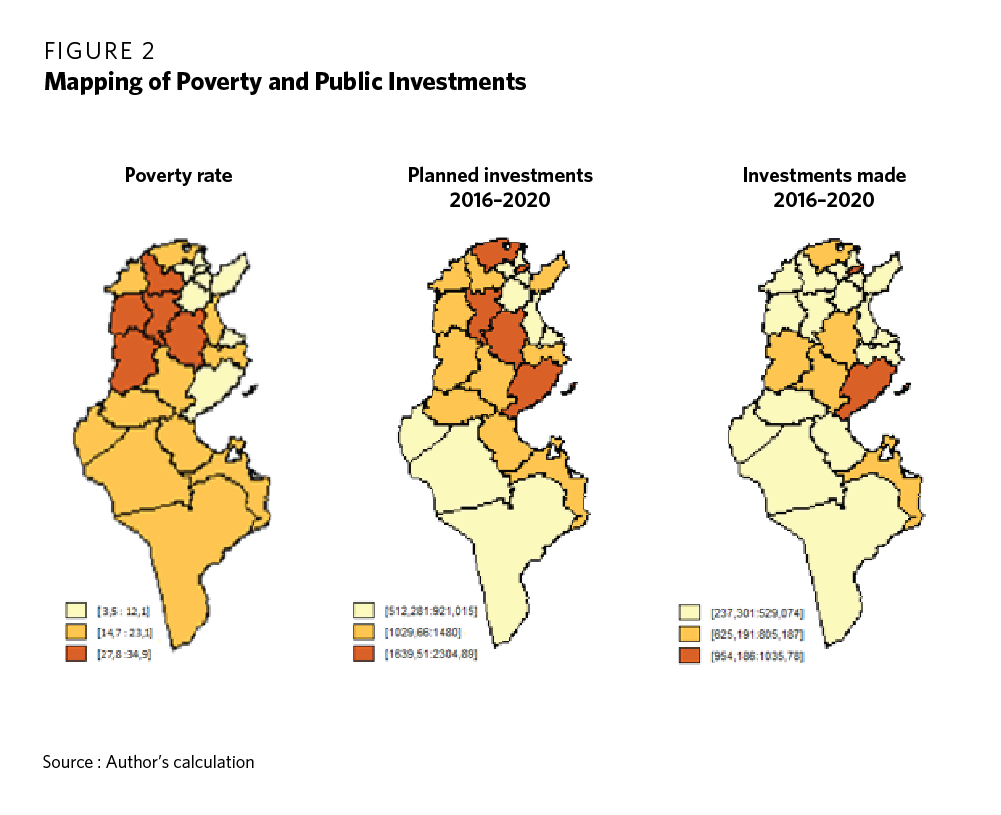

Maps on poverty and completed public investment projects (below) show that the poorest regions of the country have continuously received the lowest investment, which inhibits the possibility of growth and achieving regional equality, analyst Manel Dridi writes for Carnegie’s Sada journal.

Some secular democrats in Tunisia have defended Saied’s ‘exceptional measures’, including the suspension of parliament, as justified by the activities of the Islamist Ennahda party.

But religious actors have had a waning influence in politics in the Arab world over the past 20 years, according to Carnegie analysts Yasmine Farouk and Georges Fahmi observe. Five specific trends show this decline, they write:

- The first trend was the growth of political initiatives that were led by secular civil society voices rather than Islamist ones. …. And in the early 2000s, those coalitions extracted concessions from some incumbent regimes—such as introducing municipal elections in Saudi Arabia and opening limited space for the Kefaya movement in Egypt. Arab societies were entering a post-Islamist era where personal piety took precedent over political projects…..

-

CSID

The second trend came with the waning influence of political Islam in the aftermath of the 2011 Arab revolutions. The end of Islamist public influence was violent in some countries, like Egypt and Saudi Arabia. In other cases, dominant Islamist groups—like Ennahda in Tunisia and the Justice and Development Party in Morocco—decided to readjust their Islamist projects to the changing political climate. For still other Islamist parties, movements, militias, and extremists, popular or electoral contestation signaled Islamism’s backslide….

- The third trend has been political authorities’ attempts to push back against already contested official religious establishments. In Egypt, President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi has questioned official interpretations of Islamic laws that regulate Egyptians’ personal and everyday lives. In Saudi Arabia, the state is unprecedently taming the religious establishment and restricting its presence and influence over the public space. Post-2011 Tunisia adopted equality laws that counter predominant Sunni interpretations of inheritance and marriage, and Sudan’s post-2019 transitional government scrapped Islamist laws that governed some personal freedoms.

- The fourth trend is the backlash against violent Islamist movements—like the self-proclaimed Islamic State—that hijacked Arab uprisings. Arab regimes and their local allies used the Islamic State’s ruthless and bloody governance style to further terrorize the wider public from any form of alternative government, particularly an Islamist one. Yet in the end, it was the Islamic State’s ruthless targeting of its own Muslim communities, its negative impact on the international image of Islam and Muslims, and its feeding into Islamophobia that prompted independent thought leaders and wider Arab public opinion to repudiate it.

- A fifth, more recent, trend is currently contributing to the pushback against political Islam in the Arab world: the diminishing political support from regional states like Qatar and Turkey to Islamist groups in the region, such as the Muslim Brotherhood. This shift is driven by two main factors:

- First, it comes as a result of the failure of political Islamist groups, such as the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, to maintain their political significance.

- Second, it allows these regional states and other regional anti-Islamist regimes to reconcile, as is the case with the Qatari-Egyptian reconciliation. RTWT

Tunisia: A Failed Democratic Experiment? – Georgetown Journal of International Affairs https://t.co/48zRfw3poV

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) November 16, 2021