Americans are not retreating into isolationism, but neither are they persuaded by the traditional justifications for efforts to shape the world, notes Johns Hopkins University Professor Hal Brands.

For those who believe that American global engagement has been a good thing for the country and the world, a recent opinion survey conducted by the Center for American Progress provides reason for optimism and pessimism alike. While a majority believe the U.S. must remain competitive in the world, they are wary of prolonged wars in the greater Middle East and show limited enthusiasm for promoting democracy, he writes for Bloomberg.

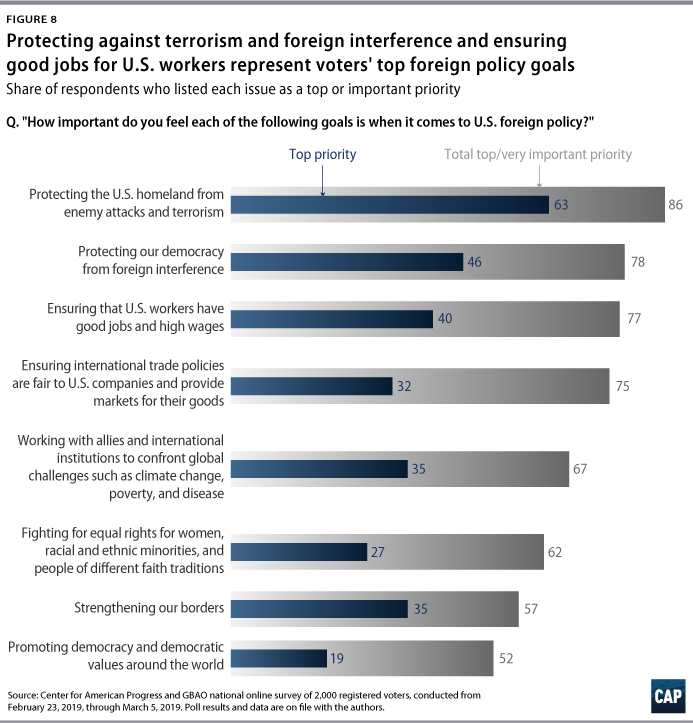

“Respondents did support efforts to protect U.S. democracy from foreign interference, advance common goals with allies, and promote equal rights in other countries. But these are second-order preferences,” the survey found. “In the hierarchy of concerns about foreign policy, terrorism and a strong economy are more immediate issues for voters than are efforts to advance democratic values around the world,” according to America Adrift: How the U.S. Foreign Policy Debate Misses What Voters Really Want, by John Halpin, Brian Katulis, Peter Juul, Karl Agne, Jim Gerstein, and Nisha Jain.

“Respondents did support efforts to protect U.S. democracy from foreign interference, advance common goals with allies, and promote equal rights in other countries. But these are second-order preferences,” the survey found. “In the hierarchy of concerns about foreign policy, terrorism and a strong economy are more immediate issues for voters than are efforts to advance democratic values around the world,” according to America Adrift: How the U.S. Foreign Policy Debate Misses What Voters Really Want, by John Halpin, Brian Katulis, Peter Juul, Karl Agne, Jim Gerstein, and Nisha Jain.

While some 27 percent of respondents believe that “fighting for equal rights for women, racial and ethnic minorities, and people of different faith traditions” should be a top priority, only 19 percent feel similarly about “promoting democracy and democratic values around the globe.”

Is the United States still in favor of promoting democracy? Anne Applebaum asks in The Washington Post. Or has its position toward democracy promotion shifted from tepid to outright hostility, as analysts Jeffrey Smith and Hilary Matfess argued recently in Foreign Policy?

Even in the best of times, the United States’ ability to influence events in faraway places is limited, notes Applebaum, a National Endowment for Democracy board member:

Even in the best of times, the United States’ ability to influence events in faraway places is limited, notes Applebaum, a National Endowment for Democracy board member:

The tools we have, from soft power and diplomacy to sanctions and bombing campaigns, are never guaranteed to succeed. The best strategies take years, even decades, to achieve anything at all: The Cold War was won, in part, thanks to small investments in the journalism of Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty, all of which would have looked like a waste of money in the 1960s, or even the 1980s. But successive administrations kept them up because they were part of a larger plan, and an international orientation that was accepted by Democrats and Republicans alike.

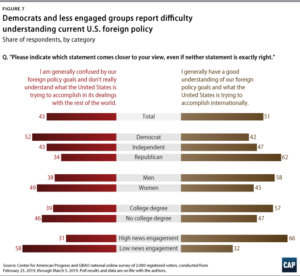

Traditional language from foreign policy experts about “fighting authoritarianism and dictatorship,” “promoting democracy,” or “working with allies and the international community” uniformly fell flat with voters, the CAP adds:

Traditional language from foreign policy experts about “fighting authoritarianism and dictatorship,” “promoting democracy,” or “working with allies and the international community” uniformly fell flat with voters, the CAP adds:

Some participants questioned the idea that an international community actually exists. Democracy promotion reminded others of the 2003 Iraq War and the failures of the George W. Bush administration. When asked what the phrase “maintaining the liberal international order” indicated to them, all but one of the participants in our focus groups drew a blank. Voters across educational lines simply did not understand what any of these phrases and ideas meant or implied.

Many liberal internationalists are interested in democracy promotion, but progressives are more interested in democracy protection or democracy preservation, argues Ganesh Sitaraman, a professor of law at Vanderbilt, co-founder of the Great Democracy Initiative, and author of The Crisis of the Middle Class Constitution.

Some 68% of CAP survey respondents agreed strongly with the assertion that “In order to remain competitive in the world, the United States must invest more to improve our own infrastructure, education and health care, not just increase military and defense spending.”

With respect to great-power competition, many of the investments will need to make to stay ahead of China — in education, basic research, advanced technology and the like — will make America stronger and more prosperous at home, adds Brands, the co-author of “The Lessons of Tragedy: Statecraft and World Order.” And the reason for investing in alliances, military power, and other competitive tools is that we don’t end up in a showdown because Moscow or Beijing think they can successfully take on the U.S.