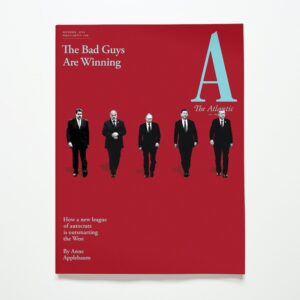

Despite years of warning, the U.S. and its allies aren’t ready for the challenges created by a coterie of Eurasian autocrats, argues Aaron MacLean, a senior fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies. The habits of mind prevalent among democratic peoples and their leaders have left us vulnerable more than once, and thus bear some examination. The principal error is thinking that men like Vladimir Putin, Xi Jinping and Ali Khamenei want what most Westerners want. They don’t, he writes for The Wall Street Journal:

Despite years of warning, the U.S. and its allies aren’t ready for the challenges created by a coterie of Eurasian autocrats, argues Aaron MacLean, a senior fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies. The habits of mind prevalent among democratic peoples and their leaders have left us vulnerable more than once, and thus bear some examination. The principal error is thinking that men like Vladimir Putin, Xi Jinping and Ali Khamenei want what most Westerners want. They don’t, he writes for The Wall Street Journal:

These rulers take risks their Western counterparts could never stomach because they think differently. They are educated in the much harder school of autocratic politics, and they are aware of a range of human ambitions that modern liberal states, from their earliest foundations, have sought to suppress in the name of peace and comfort. … Russia, China and Iran each present their own complex, albeit related, problems, and the objectives and ideologies of their leaders are different. But they all are encouraged in their recklessness by fantasies that have long plagued modern democracies.

The United States has shifted into retrenchment mode, another such cycle in U.S. history, which spells opportunities for the revisionist trio of Russia, China, and Iran, says Josef Joffe at Johns Hopkins SAIS.

The United States has shifted into retrenchment mode, another such cycle in U.S. history, which spells opportunities for the revisionist trio of Russia, China, and Iran, says Josef Joffe at Johns Hopkins SAIS.

America is now up against two global foes who are both arrayed against the United States. It is imprisoned in a three-dimensional chess game where Russia and China are ganging up on the status quo power, he writes for American Purpose. Beijing’s and Moscow’s strategy is as simple as it is refined: Use your local advantage and get there first.

Make the case for democratic fundamentals

Framing democracy in instrumental terms, as a political system that can “‘deliver’ prosperity and security in a way that autocracies cannot” mistakenly suggests that democracy is important only to the degree that it provides material benefits, note Council on Foreign Relations experts Stewart M. Patrick and . Autocracies often invoke the same logic to justify their regimes and repudiate democracies that fail to record similar progress. Instead of playing into [their] hands, open societies should, as Jan-Werner Müller argues, “make the case for democracy [on] its fundamentals,” they contend:

The arrival of a new year is often a time when people take a hard look at themselves and resolve to do better. For the Biden administration, it also offers an opportunity to ask what the United States can do, in the coming “year of action,” to better protect and promote its own democratic experiment, to affirm the intrinsic values of democracy, and to restore the nation’s legacy as a beacon for others. At midnight on January 1, the United States should save a toast for democracy—and then “get to work.”

The arrival of a new year is often a time when people take a hard look at themselves and resolve to do better. For the Biden administration, it also offers an opportunity to ask what the United States can do, in the coming “year of action,” to better protect and promote its own democratic experiment, to affirm the intrinsic values of democracy, and to restore the nation’s legacy as a beacon for others. At midnight on January 1, the United States should save a toast for democracy—and then “get to work.”

At least three democracies will decide the fate of leaders (or the kin of leaders) with distinctly authoritarian inclinations, TIME reports.

The primary threats to U.S. security come from states that deny freedom to their own people, according to the Forum on American Leadership, a center-right policy forum. The United States has interests in encouraging responsible and representative governments that uphold fundamental human rights, including a free press and the right of individuals to live according to the dictates of their god. Achieving this requires acknowledgment of the contrast between the nature and behavior of the regimes that threaten America’s interests and those in the democratic world. The very nature of the American experiment is a structural and competitive advantage, it adds.

We are fast approaching a point where a crisis in Eastern Europe, especially the fate of Ukraine, could decide Europe’s security, and by extension, its political future, says Andrew Michta of the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies. What European governments do going forward will either reaffirm the interests and values of Western democracies or will become our greatest defeat since the end of the Cold War. It is a binary choice that cannot be wished away or obfuscated by compromise, he writes for 1945.

In its vision of what it means to be civilized, the republication of Thomas Mann’s Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man, in which he argues against the imposition of Western liberal democracy, is surprisingly timely, the critic Adam Kirsch observes. In the twenty-first century, similar protests against the arrogance of Western democracy can be heard from authoritarian rulers in Russia and China, who insist that universal ideas of human rights are unsuited to their peoples, he writes for City Journal.

A few years later, it would all come crashing down and he would emerge on the opposite side, a supporter of democracy, humanism, and Western values. The ultimate failure of Mann’s protest in Reflections is crucial to remember, even as his arguments continue to exert a genuine, heretical power, Kirsch concludes.

A few years later, it would all come crashing down and he would emerge on the opposite side, a supporter of democracy, humanism, and Western values. The ultimate failure of Mann’s protest in Reflections is crucial to remember, even as his arguments continue to exert a genuine, heretical power, Kirsch concludes.

Democracies’ discounting of threats is nothing new, FDD’s MacLean adds. In his 1919 classic, “Democratic Ideals and Reality,” the British strategist Halford Mackinder noted that modern democracy is essentially idealistic, aiming toward the goal that “every human being shall live a full and self-respecting life.” Such idealism left democracies prey to men like the German Kaiser. “Democracy refuses to think strategically unless and until compelled to do so for purposes of defense,” Mackinder observed with the bitter consequences of the Great War in mind. RTWT

Join American Purpose for a conversation with Fareed Zakaria on “The Narrow Path to Liberal Democracy.” January 4, 2022. 12 p.m. ET. Register